Advisory Opinion 283

Parties: Jacob and Tamara Schellenberg / Cache County

Issued: January 22, 2024

...

Topic Categories:

Exactions

The County’s ordinances requiring that adjacent roadways meet minimum established roadway standards a condition of subdivision plat approval is legal on its face. Similarly, the County may lawfully impose an in-lieu fee as an alternate method of improving the roadway to established standards.

However, when applied to the circumstances at hand, this standard requires the Property Owners to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole. The County may only require that any individual subdivider dedicate and improve the half-width adjacent to their property as a condition of development. To require dedication and improvement of the full-width of an adjacent roadway requires the subdivider to pay beyond their impact and appears to violate both the U.S. and Utah Constitutions takings clauses.

DISCLAIMER

The Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman makes every effort to ensure that the legal analysis of each Advisory Opinion is based on a correct application of statutes and cases in existence when the Opinion was prepared. Over time, however, the analysis of an Advisory Opinion may be altered because of statutory changes or new interpretations issued by appellate courts. Readers should be advised that Advisory Opinions provide general guidance and information on legal protections afforded to private property, but an Opinion should not be considered legal advice. Specific questions should be directed to an attorney to be analyzed according to current laws.

Advisory Opinion

Advisory Opinion Requested by:

Local Government Entity:

Applicant for Land Use Approval:

Type of Property:

Residential

Opinion Authored By:

Marcie M. Jones, Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

Issue

May the county lawfully require a property owner to both (1) pay $163,961 for the improvement of the full width of an adjacent local roadway as well as (2) dedicate 0.43 acres of land to allow the roadway to be straightened, as a condition of approval for a 3-residential lot subdivision?

Summary of Advisory Opinion

The county’s ordinances requiring that adjacent roadways meet minimum established roadway standards a condition of subdivision plat approval is legal on its face. Similarly, the county may lawfully impose an in-lieu fee as an alternate method of improving the roadway to established standards.

However, when applied to the circumstances at hand, this standard requires the property owners to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole. The County may only require that any individual subdivider contribute to public improvements according to the proportionate share of their development impact. It would be roughly proportionate to require the property owners to contribute the equivalent of the dedication and improvement of the half-width of road improvements adjacent to their property as a condition of development. To require dedication and improvement of the full-width of an adjacent roadway requires the property owners to pay for more than their own impact and appears to violate both the U.S. and Utah Constitutions takings clauses.

Evidence

The following documents and information with relevance to the issue involved in this Advisory Opinion were reviewed prior to its completion:

- Request for Advisory Opinion submitted by Jacob and Tamara Schellenberg on May 22, 2023.

- Letter from K. Taylor Property Owners on behalf of Cache County on July 18, 2023.

Background

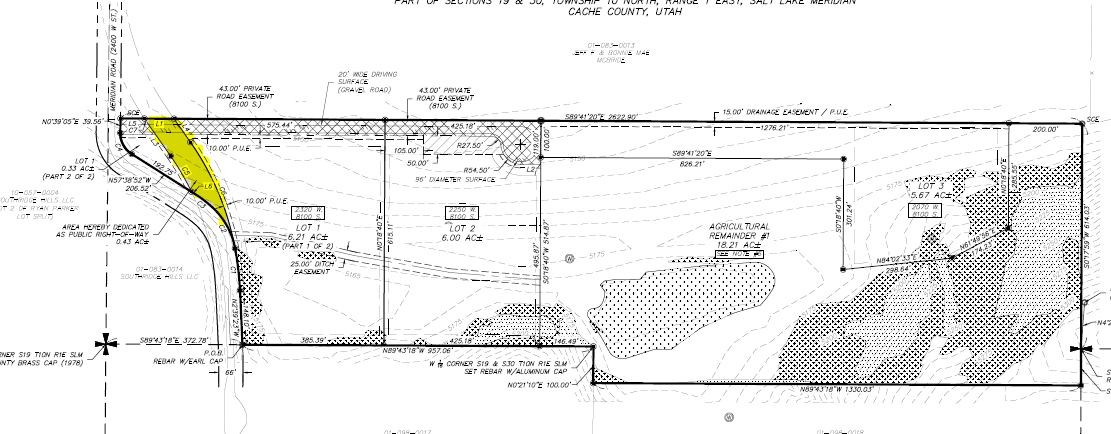

Jacob and Tamara Schellenberg (Property Owners) own vacant land located in unincorporated Cache County (County). The Property Owners are seeking approval of a three-lot residential subdivision on approximately 36 of the acres. The property abuts 2400 West, also known as Meridian Road, which is a county road that connects the Town of Paradise with the rest of the valley. As a condition of approval, County is requiring that the Property Owners pay $163,961.30 as a fee-in-lieu for improvement of the full-width of the adjacent roadway. Additionally, the County is requiring that the Property Owners dedicate to the public 0.43 acres of property required to straighten out the roadbed.

The exhibit above shows the proposed 3-lot subdivision as well as the existing roadway. The 0.43 acres to be dedicated to allow straightening of the road bed has been highlighted.

The Property Owner questions whether this fee and land dedication requirement is legal. They claim that there are many roads in the county which are smaller, gravel roads. When they purchased the property, the County told them that “very little improvements” were required to satisfy the current road status, then, without notice, the status of the road was changed and new standards adopted.

The County maintains that they are simply requiring the Property Owners to meet the standards established by generally applicable ordinance. The County has also stated that the area of proposed development is very rural and fairly mountainous and that areas containing steep slopes are more costly than developing flat properties. The fee-in-lieu allows the development of a length of roadway to be completed at one time.

The County is also requiring dedication of 0.43 acres of land so that turns in Meridian Road can be straightened as it passes the subject property, as required by the adopted roadway standards. Apparently, cars often get stuck on this section of the road in snowy and icy conditions. Rerouting the roadway cuts off 0.33 acres of property from development. The Property Owners question whether this requirement is legal.

The Property Owners believe these exactions require them to give more than their proportionate share. The Property Owners have therefore requested this Advisory Opinion to answer whether the County may lawfully require the property owner to both (1) pay $163,961 for the improvement of the full width of an adjacent roadway as well as (2) dedicate 0.43 acres of land to allow the roadway to be straightened as a condition of approval for a 3-residential lot subdivision.

Analysis

When we examine whether an ordinance is lawful, we first ask whether it is legal on its face, or in other words, whether the ordinance is legal as it written. This inquiry asks whether the ordinance violates state or federal constitutional or other laws. We next inquire whether the ordinance is legal as applied to a particular set of circumstances. A law may be within the legal bounds as written, yet nonetheless exceed authority when applied to a particular instance.

I. Counties may require that roadways meet minimum established standards before approving a subdivision plat.

Our initial question is whether the County may require that roadways be improved as a condition of development. It has not been disputed that the language of the County Code requires that the roadway width adjacent to the Property be dedicated and improved as a condition of approval of the Property Owners’ three-lot subdivision.

Cache County Code § 12.02.020 reads “where land abutting an existing substandard roadway is subdivided or developed, the subdivider or developer must, at the subdivider’s or developer’s expense, dedicate any necessary rights-of-way and improve the adjacent roadway to conform to the standards and requirements set forth in the Manual.” The referenced manual incorporates standards from UDOT and national road experts.

The Property Owners have not disputed that the language of the County Code requires these improvements. The question, therefore, is whether the County may legally set such standards, and also, whether these standards are lawful as applied to this subdivision.

It is established that an owner of property holds it subject to zoning ordinances enacted pursuant to a state's police power. Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365, 71 L. Ed. 303, 47 S. Ct. 114 (1926). Police power is “the power of the states to regulate behavior and enforce order within their territory for the betterment of the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of their inhabitants.” Police Power, Encyclopedia Britannica (2023, May 25). The U.S. Supreme Court has further held that the valid exercise of police power includes land use regulations. See, e.g. Euclid v. Ambler Realty, 272 U.S. 365 (1926). The enactment of a standard land use ordinance is a legislative decision subject to the “reasonably debatable” test whereby a reviewing court must presume that a properly enacted land use regulation is valid and determine only whether “it is reasonably debatable that the land use regulation is consistent with [applicable state law]” and therefore in the interest of the general welfare. Utah Code § 10-9a-801(3)(a).

The “reasonably debatable” test is, generally, a low bar. On its face, it is “reasonably debatable” that the disputed requirements are in the interest of the general welfare of the citizens where the County has a duty to provide streets, sewage disposal, and clean water for residents. Whether or not a County enacts ordinances that allow for more affordable rural development that would permit construction of large residential lots without requiring roadway improvement is a policy decision left to the local elected officials.

Therefore, the answer to the first question is yes, the County may require that the adjacent roadways meet the minimum established roadway standards as a condition of subdivision plat approval. Similarly, the County may impose an in-lieu fee as an alternate method of improving the roadway to established standards.

II. Requiring the Property Owner to dedicate and improve the entire width of the adjacent roadway exceeds the impact of development and therefore cannot constitute a valid exaction.

The next step is to apply the standard to the circumstances at hand. May the County lawfully require the Property Owners to pay $163,961 as an in-lieu payment for roadway improvements and dedicate 0.43 acres of land to the County as a condition of approval of a three-lot residential subdivision?

A. The legal standard for development exactions

Cache County’ requirement that the Property Owners pay $163,961 as in-lieu payment for roadway improvements and dedicate 0.43 acres of land to the County as a condition of approval of a three-lot subdivision is a development exaction. A development exaction “is a government-mandated contribution of property imposed as a condition” of development approval. B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake County, (BAM III), 2012 UT 26, ¶16.

The Takings Clause of the U.S. Constitution[1] protects private property from governmental taking without payment. It reads, “[n]or shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” United States Constitution, 5th Amendment. “One of the principal purposes of the takings clause is to ‘bar Government from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole.’” Dolan v. County of Tigard, 512 U.S 374 (1994) quoting Armstrong v. United States, 364 U.S. 40, 49, L. Ed. 2d 1554, 80 S. Ct. 1563 (1960).

As a result, generally speaking, the government may not require a property owner to donate land or improvements to the public unless they are prepared to pay for that dedication. However, a government entity may require dedication of land and/or improvements as a condition of development approval to the extent the dedication offsets only the impact the development will put on the community. Such a requirement will not be considered a taking requiring just compensation.

Accordingly, an exaction is valid and proportionate only when it offsets the costs of a development’s impact, and no more. An excessive exaction amounts to an unconstitutional taking where it requires a property owner to pay for impacts beyond his own. Banberry Development Corporation v. South Jordan County, 631 P.2d 899, 903 (Utah 1981). A principal objective of the test is to “bar Government from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole.” Armstrong v. United States, 364 U.S. 40, 49 (1960). Therefore, the community may require dedication of land or construction of public resources such as roadways and water lines as long as the requirements offset only the impact of proposed development.

The determination of how to measure whether the dedication offsets the impact of development has been termed the “rough proportionality test,” and was established in the groundbreaking U.S. Supreme Court cases Nollan v. California Coastal Comm’n, 483 U.S. 825 (1987) and Dolan v. County of Tigard, 512 U.S 374 (1994) and codified in Utah Code § 10-9a-508(1).

A municipality may impose an exaction or exactions on development proposed in a land use application . . ., if:

(a) an essential link exists between a legitimate governmental interest and each exaction; and,

(b) each exaction is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.

Utah Code § 10-9a-508(1) (emphasis added). If a proposed exaction satisfies this test, and is otherwise legal, it is valid. If the exaction fails the test, it violates protections guaranteed by the Takings Clauses of the Utah and U.S. Constitutions and is illegal. Call v. West Jordan, 614 P.2d 1257, 1259 (Utah 1980). Accordingly, we next analyze the exactions to determine whether they satisfy the rough proportionality test.

B. Essential link exists between legitimate governmental interest and the required exaction

The first part of the rough proportionality test, as codified in Utah Code § 10-9a-508(1) requires an essential link between a legitimate governmental interest and the exaction imposed. The County’s requirement to dedicate and improve property along the right-of-way along Property Owners’ frontage is based in the County’s legitimate interest in protecting and promoting public health, safety, and welfare. “In order for a government to be effective, it needs the power to establish . . . public throughways. . . for the convenience and safety of the public.” Carrier v. Lindquist, 2001 UT 105, ¶ 18.

Accordingly, the essential link portion of the rough proportionality test is satisfied.

C. Nature aspect of the rough proportionality test satisfied

The next step in the rough proportionality test requires that “each exaction is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.” Utah Code §10-9a-508(1)(b). The nature aspect of the rough proportionality test requires that an exaction provide a solution to a problem the proposed development presents. The Property Owners propose to divide their acreage into three residential lots. The roadway adjacent to and directly serving the Property lacks an improved roadway. The proposed development is in a very rural area at the base of a collection of hills in an unincorporated portion of the County.

The required land dedication is immediately adjacent to the property and once improved with the required in-lieu fee, would provide access to the residents and guests of the proposed residences. Therefore, the exaction directly provides a solution to the problem the proposed development creates. Accordingly, the nature aspect of the test is satisfied.

D. Extent aspect of the rough proportionality test exceeded

In the final step of the rough proportionality test, the County must “compare the government’s cost of alleviating the development’s impact on infrastructure with the cost to [the developer] of the exaction,” therefore looking at whether the exaction is proportional in extent. B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake County, 2012 UT 26, ¶5, 282 P.3d 41.

The Utah Supreme Court has provided a single example of how to balance extent. Id. In B.A.M. II, the Court held that requiring the dedication of 13 feet of right-of-way for the expansion of an adjacent roadway as a condition of approval of a fifteen-acre residential subdivision satisfied the extent aspect of the rough proportionality test. In that case, traffic engineers estimated increased traffic from the planned subdivision represented 5% of the total area-wide traffic increase yet the cost of the disputed dedication amounted to only 1% of area-wide road improvement projects.[2] Therefore, the Court concluded that the exaction was less than the impact and did not violate the extent aspect of the rough-proportionality standard.

In the case at hand, “[n]o precise mathematical calculation is required” however, the County must nonetheless make “some sort of individualized determination that the required dedication is related both in nature and extent to the impact of the proposed development.” See Dolan, 512 U.S. at 391-92 (emphasis added).

The County has not provided a monetary cost for the impact of the proposed development. Instead, the County provides a logical argument that the proposed development is in a very rural area at the base of a collection of hills in an unincorporated portion of the County. By developing on this site, the Property Owners are pulling County services, including roadway improvements, beyond their current limits. The County maintains that the development will result in an increase in traffic from trash collection, snow removal, school bus trips, deliveries, EMS, fire, law enforcement, as well as domestic trips – all of which will impact on County roads.

The County states that it is only requiring that the applicant fund the portion of the frontage adjacent to their development. The County explains, without giving specific dollar figures or pointing to particular proposed improvement projects, that the total cost and impact for all county road improvements in the area will be hundreds of thousands of dollars. The County is requiring that the Property Owner pay the actual cost estimate provided by the Property Owner’s own engineer, of improving that portion of the roadway abutting the proposed subdivision.

While logical, the County’s argument is not substantiated by sufficient detail to allow us to perfectly evaluate the lawfulness of the exaction. Indeed, we note that in our years of writing Advisory Opinions on exactions, such detailed information has never been available and may be out of reach for the standard land use application. As a result, and in an attempt to resolve disputes, past Advisory Opinions have articulated a commonly used industry standard:

It is common for a county to exact the dedication and construction of a half-width of a road, curb, gutter, etc., along the entire frontage of the property. This half-width frontage dedication and construction is common practice and generally accepted as roughly proportionate to a typical road impact. An abutting half-width generally does not require one developer to provide improvements that others should provide — i.e., the opposite abutting landowner typically provides the other half-width.[3]

The requirement for a subdivider to dedicate and improve the half-width of the local roadway fronting the property is a common standard, and one that appears to be widely credible throughout the development community. It is grounded in the need for a practical, straight-forward standard to apply in the thousands of land use application approvals made across the state each year.

This half-width standard corresponds to the legal standard explained in relevant Utah court cases and is reasonable on its face. If everyone in the County improves the local roadway half-width adjacent to their property when they develop, we have local roadways that we all can use. Larger lots require more roadway and smaller lots require less roadway - thus balancing proportionality.

In this case, the County is asking for the Property Owner to dedicate the land under the full width of the straightened roadway, as well as pay the value to improve the full width of the adjacent roadway. This requires the Property Owner to pay beyond their own impact. It exceeds the half-width standard. In the absence of detailed analysis establishing otherwise, the County may lawfully require the Property Owner to pay an in-lieu fee equivalent to improving the half-width of the roadway, and dedicate land required to improve the half-width of the straightened roadway. The County may exact the other half-width when owners on the far side of the road develop. If the County is unwilling to wait for development on the other side of the road to occur, the County must be prepared to bear the remaining share of the public’s burden for its desired road project that is intended to benefit the larger community.

Consequently, the County’s requirement to dedicate the full width of the straightened-out portion as well as an in-lieu fee to improve the full width of the adjacent roadway exceeds Property Owners’ impact on development and appears to violate the takings clause.

Conclusion

The county’s ordinances requiring that adjacent roadways meet minimum established roadway standards as a condition of subdivision plat approval is legal in general and on its face. Similarly, the county may lawfully impose an in-lieu fee as an alternate method of improving the roadway to established standards.

However, when applied to the circumstances at hand, this standard requires the property owners to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole. The County may only require that any individual subdivider contribute to public improvements according to the proportionate share of their development impact. It would be roughly proportionate to require the property owners to contribute the equivalent of the dedication and improvement of the half-width of road improvements adjacent to their property as a condition of development. To require dedication and improvement of the full-width of an adjacent roadway requires the property owners to pay beyond their impact and appears to violate both the U.S. and Utah Constitutions takings clauses.

...

...

Jordan S. Cullimore, Lead Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

...

NOTE:

This is an advisory opinion as defined in § 13-43-205 of the Utah Code. It does not constitute legal advice, and is not to be construed as reflecting the opinions or policy of the State of Utah or the Department of Commerce. The opinions expressed are arrived at based on a summary review of the factual situation involved in this specific matter, and may or may not reflect the opinion that might be expressed in another matter where the facts and circumstances are different or where the relevant law may have changed.

While the author is an attorney and has prepared this opinion in light of his understanding of the relevant law, he does not represent anyone involved in this matter. Anyone with an interest in these issues who must protect that interest should seek the advice of his or her own legal counsel and not rely on this document as a definitive statement of how to protect or advance his interest.

An advisory opinion issued by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman is not binding on any party to a dispute involving land use law. If the same issue that is the subject of an advisory opinion is listed as a cause of action in litigation, and that cause of action is litigated on the same facts and circumstances and is resolved consistent with the advisory opinion, the substantially prevailing party on that cause of action may collect reasonable attorney fees and court costs pertaining to the development of that cause of action from the date of the delivery of the advisory opinion to the date of the court’s resolution. Additionally, a civil penalty may also be available if the court finds that the opposing party—if either a land use applicant or a government entity—knowingly and intentionally violated the law governing that cause of action.

Evidence of a review by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman and the opinions, writings, findings, and determinations of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman are not admissible as evidence in a judicial action, except in small claims court, a judicial review of arbitration, or in determining costs and legal fees as explained above.

The Advisory Opinion process is an alternative dispute resolution process. Advisory Opinions are intended to assist parties to resolve disputes and avoid litigation. All of the statutory procedures in place for Advisory Opinions, as well as the internal policies of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman, are designed to maximize the opportunity to resolve disputes in a friendly and mutually beneficial manner. The Advisory Opinion attorney fees and civil penalty provisions, found in § 13-43-206 of the Utah Code, are also designed to encourage dispute resolution. By statute they are awarded in very narrow circumstances, and even if those circumstances are met, the judge maintains discretion regarding whether to award them.

...

Endnotes

_____________________________________________

[1] Also Article I Section 22 of the Utah Constitution.

[2] The estimated value of total area-wide road improvements was $6,748,700 and the value of the property to be dedicated was $83,997, representing 1.2% of the total.

[3] Ombudsman Advisory Opinion 205. See also Ombudsman Advisory Opinions 221 and 180. While not legally binding, our Office does endeavor to issue opinions using consistent analysis and reasoning.