Advisory Opinion 279

Parties: 1115 Aerie, LLC

Issued: November 16, 2023

...

Topic Categories:

Application Review Fees

Compliance With Land Use Regulations

The City’s denial of a conditional use permit for approval of an existing unpermitted private recreational sports court was wrongful as the City erred in (1) misinterpreting the subdivision plat as prohibiting further development of the lot, and (2) concluding it had received insufficient information to determine compliance with steep slope requirements and other conditional use standards.

Ambiguous plat depictions may be resolved with extrinsic evidence of the plat approval’s legislative history and ordinances in effect at the time. Prior City ordinances allowed for prospective development restrictions by plat, but only if defined and clearly stated on the plat. As the City erred in finding the plat imposed such development restrictions, the City otherwise erred in denying the conditional use permit application for insufficient information when the applicant had requested a continuance to provide the necessary information. Cities bear the burden of obtaining sufficient information through substantive review before proceeding with final action on an application in order to avoid arbitrary decisions.

DISCLAIMER

The Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman makes every effort to ensure that the legal analysis of each Advisory Opinion is based on a correct application of statutes and cases in existence when the Opinion was prepared. Over time, however, the analysis of an Advisory Opinion may be altered because of statutory changes or new interpretations issued by appellate courts. Readers should be advised that Advisory Opinions provide general guidance and information on legal protections afforded to private property, but an Opinion should not be considered legal advice. Specific questions should be directed to an attorney to be analyzed according to current laws.

Advisory Opinion

Advisory Opinion Requested by:

Local Government Entity:

Applicant for Land Use Approval:

Type of Property:

Residential

Opinion Authored By:

Richard B. Plehn, Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

Issues

Was 1115 Aerie entitled to approval of the Conditional Use Permit Application it submitted to the Park City Planning Commission for a sports court as a “Private Recreation Facility”?

Summary of Advisory Opinion

The applicant’s residential property is a lot in a master planned development subdivision located in the city’s Estate district and subject to the sensitive lands overlay. The applicant is seeking to legalize certain prior land disturbance and development activity that had initially commenced without proper permits, and applied for conditional use approval of a sports court.

Final action on conditional use applications must include findings according to conditional use standards and must be supported by substantial evidence. It is incumbent on the city to use the substantive review process to obtain all information necessary before considering a matter for final decision. Unless the applicant demands final action, “insufficient information” is not a valid basis for denial where the application could be continued to obtain information necessary for required findings. Conditional uses, like any land use application, must also comply with the objective requirements of land use regulations, development standards, and applicable land use decisions, including plat restrictions. Plats are interpreted to discern the meaning of the parties at the time the plat is created, and ambiguity is appropriately resolved by the extrinsic evidence of subdivision approval documents and the land use ordinances in effect at the time of approval.

The city wrongfully interpreted platted building pad lines as proscribing any development activity beyond the existing home’s footprint, which was not the intent of the plat according to the master planned development approval and ordinances in effect at that time. The city also concluded that it had insufficient information about the lot’s pre-development condition in order to determine compliance with standards for steep slopes and vegetation protection. Despite the applicant’s preference to continue the matter to provide the necessary information, the city wrongfully denied the application for “lack of information” and for noncompliance with original plat restrictions, which was erroneous.

The city should reconsider the application without regard to any plat restrictions, and only after it has received whatever information it feels is necessary to determine compliance with steep slope regulations and to make required findings under its conditional use standards of reasonably anticipated detrimental effects, and the potential mitigation of those effects by condition. It must then approve the conditional use permit if it determines the application, as conditioned, achieves compliance with its standards, or else deny the permit if it determines objective requirements are not met or that reasonable conditions cannot substantially mitigate identified detrimental effects.

Evidence

The Ombudsman’s Office reviewed the following relevant documents and information prior to completing this Advisory Opinion:

- Request for Advisory Opinion submitted by Wade Budge, Attorney for 1115 Aerie, LLC, received on August 2, 2022.

- Response Letter from Park City, received on February 13, 2023.

- Reply letter from Wade Budge, received on March 8, 2023.

- Park City’s Response to March 8, 2023 reply, received March 13, 2023.

- Wade Budge reply to City’s March 13, 2023 response, received on March 17, 2023.

- Letter from Wade Budge re: Supplemental Information, dated July 20, 2023.

Background

1115 Aerie Drive, in Park City, is owned by an LLC of the same name, 1115 Aerie, LLC (Aerie). The property is a residential lot within a subdivision originally approved as a 12-lot Master Planned Development in 1993. The subdivision plat depicts on each lot a 90’ x 90’ area noted as “building pad.” A home was later built in 1998 which utilized the lot area noted as building pad.

Aerie hired a landscaping contractor to landscape, retain, and build improvements on the Property, including a large sports court. The contractor represented to Aerie that it had obtained all necessary permits for the work. Unfortunately, the contractor had not, in fact, done so. While the contractor did apply for a grading/landscaping permit in January of 2021 to replace three retaining walls, the remainder of the work, including the sports court, had not been permitted by Park City (City).

In September 2021, after much work had been performed, the City notified Aerie that the work had exceeded the scope of the issued permit and violated provisions of Park City’s Land Management Code (Code). Once Aerie learned that its contractor had failed to obtain the correct permits, it began working with the City to obtain necessary approvals and attempt to modify the contractor’s work to bring it in compliance with Code requirements.

On December 20, 2021, Aerie submitted a Conditional Use Permit Application (CUP) proposing to legalize the already constructed sports court by modifying the facility and seeking approval of the facility as a “Private Recreation Facility,” which is a conditionally permitted use in the applicable Estate Zoning District under the Code. The application proposed to significantly modify the sports court to accommodate setback requirements, reduce the overall size of the court to minimize disturbance, and increase the amount of vegetative screening to minimize the court’s impacts on neighbors and the community. Aerie also submitted a separate Administrative CUP application for retaining walls greater than six feet in height. On June 17, 2022, Aerie formally requested final action pursuant to Utah Code Section 10-9a-509.5(2)(b) on the Administrative CUP. Planning staff recommended that because the proposed relocated retaining wall is located directly adjacent to the sports court pad, the Planning Commission should review the Private Facility CUP for the sports court use and provide input before the administrative hearing on the retaining wall CUP.

When the private recreation facility CUP was scheduled to come before the planning commission, the staff report that accompanied the application concluded that the building pad lines depicted on the plat were intended as the limit on disturbance for the lot, and that developing outside of the building pad area violated restrictions in the plat. The report noted that the information submitted regarding lot conditions were all post-development, and that information regarding the pre-development conditions were necessary. The report referenced several pieces of information that staff felt was missing in order to determine compliance with the City’s conditional use standards, and ultimately recommended denial of the CUP “due to a lack of submitted information to date.” The report continued:

If the applicant wishes to withdraw and resubmit, the following information should be provided:

-

- Additional analysis of pre-development conditions, including identifying areas of Steep Slopes, Very Steep Slopes, and Significant Vegetation

- An explanation and proposed management for the use of the sports court

- A lighting and noise mitigation plan for the court and site

On July 13, 2022, the Planning Commission reviewed the CUP application in a public hearing. Before and during the hearing, neighbors to the Property expressed concerns that lighting and noise associated with the sports court would negatively impact them. City staff raised issues related to steeps slopes and noncompliance with prior approvals and the applicable subdivision plat.

The applicant provided an explanation of the proposed use of the sports court as well as lighting, and stated that the owner would accept certain conditions regarding use and lighting that he felt would mitigate anticipated detrimental impacts and address comments made by neighbors.

In regards to the pre-development conditions for steep slope and vegetation issues, the applicant repeatedly offered to provide more information as needed. When one commissioner expressed support for denying the permit until the applicant worked more with staff and provided more information, the applicant responded that “the applicant would be happy to provide the additional information and rather than going through the process of handling a denial, they would like to provide that information to the Commission. [Applicant] suggested a continuance would be preferable.”

Despite the request for more time to provide information that the Commission felt it was lacking, Planning Staff expressed its opinion that while more information could be helpful, even with additional information, Staff would likely still recommend denial. This appears to be, in part, due to the conclusion that the plat restricted any development outside of the building pad area, but also due to questions of whether the applicant could adequately mitigate the loss of vegetation and issues of drainage due to the amount of impervious surface and other landscaping added.

The Planning Commission therefore moved forward with denying the application. A July 20, 2022 denial letter issued by the Planning Commission listed 17 findings of fact to support its conclusions that the conditional use permit was not consistent with the conditional use standards in the Code.

These findings are distilled into two primary reasons for denial: (1) that the as-built conditions, including placement of structures like the sports court outside of the building pad area depicted on the plat violated original plat restrictions, and could not therefore be brought into compliance, and (2) the application does not meet the Code’s conditional use review process “due to a lack of information submitted regarding screening and landscaping, compatibility with surrounding structures, potential noise, lighting, environmentally sensitive lands, steep slopes, and appropriateness of the proposed Structure to the existing topography of the Site.”

Aerie contends that the City’s provided reasons for denial are legally insufficient, and that the Planning Commission therefore unlawfully denied Aerie’s conditional use permit application. Accordingly, Aerie has submitted a Request for Advisory Opinion to this Office asking us to determine whether the denial was lawful.

Analysis

Utah’s Land Use, Development, and Management Act (LUDMA), as applied to municipalities, provides that a court “shall presume that a final land use decision of a land use authority or an appeal authority is valid unless the land use decision is . . . arbitrary and capricious; or . . . illegal.” Utah Code § 10-9a-801(3)(b).

In its Request for Advisory Opinion, Aerie asserts the City’s land use authority—the Planning Commission—erred in denying Aerie’s conditional use permit application for four primary reasons. Namely, Aerie alleges, first, that the Commission improperly denied the application “for a lack of information,” instead of identifying detrimental effects and determining whether the effects could be mitigated. Second, Aerie alleges that the Commission was legally wrong in concluding that subdivision plat prohibits development of the proposed sports court outside of the platted building pad lines. Third, Aerie argues that the Commission incorrectly determined the sports court was constructed within fifty feet of a Very Steep Slope. Fourth, and finally, Aerie argues that the Commission improperly relied on aspirational or subjective provisions of the City’s general plan to deny the application.

We will address each concern, but as discussed below, we conclude that the Planning Commission erred in its interpretation that the plat restricted the proposed development, and that the development activity violated steep slope standards. Without these two reasons as independent bases for denial, the Commission likewise erred in taking final action to deny the conditional use application without the information it felt it needed to make required findings under its conditional use standards. We conclude that the reasons stated as the basis for denial in the City’s final action letter were affected by unknowns that the City acknowledges could be cleared up by additional information by the application. The Commission therefore should have continued the matter, as was preferred by the applicant, before attempting to conclude that the application did not conform to applicable standards.

I. Aerie’s Proposed Development Activity Does Not Violate Internal Lot Restrictions

A land use application is entitled to substantive review under the land use regulations in effect at the time of application. Utah Code § 10-9a-509(1)(a). However, an application must also comply with applicable land use decisions and development standards, see id., which may include “internal lot restrictions,” defined as a “platted note, platted demarcation, or platted designation that . . . runs with the land; and creates a restriction . . . [or] designates a development condition that is enclosed within the perimeter of a lot described on the plat.” Id. § 10-9a-103(27).

Here, the 1993 Hearthstone Subdivision plat that created the Aerie lot depicts, on each lot of the subdivision, a designated area labeled “90’ x 90’ BUILDING PAD”.

Relevant for our purposes, the City’s current version of the Code defines the following terms:

STRUCTURE. Anything constructed, the Use of which requires a fixed location on or in the ground, or attached to something having a fixed location on the ground and which imposes an impervious material on or above the ground; definition includes “Building”.

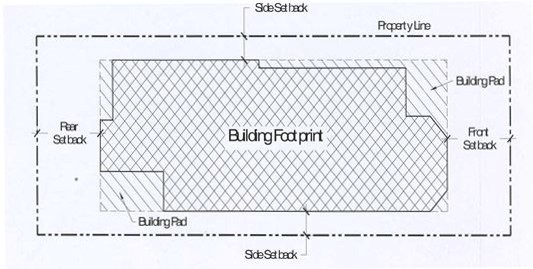

BUILDING ENVELOPE. The Building Pad, Building Footprint, and Height restrictions that defines the maximum Building Envelope in which all Development must occur.

BUILDING FOOTPRINT. The total Area of the foundation of the Structure, or the furthest exterior wall of the Structure projected to Natural Grade, not including exterior stairs, patios, decks and Accessory Buildings listed on the Park City Historic Structures Inventory that are not expanded, enlarged or incorporated into the Main Building.

BUILDING PAD. The exclusive Area, as defined by the Setbacks, in which the entire Building Footprint may be located. See the following example; also see Limits of Disturbance.

LIMITS OF DISTURBANCE. The designated Area in which all Construction Activity must be contained.

CONSTRUCTION ACTIVITY. All Grading, excavation, construction, Grubbing, mining, or other Development Activity which disturbs or changes the natural vegetation, Grade, or any existing Structure, or the act of adding an addition to an existing Structure, or the erection of a new principal or Accessory Structure on a Lot or Property.

Land Management Code (LMC) § 15-15-1.

The City concludes that the proposed sports court is a “structure” under the Code, and that demarcation of “building pad” on the subdivision plat, consistent with that term’s meaning and other related terms as currently defined in the Code, is intended to effectively act as the lot’s definitive building envelope, meaning that the plat restricts any type of development activity outside of the depicted building pad area, and since the Aerie lot has been improved with a primary structure that effectively utilized the entirety of this building pad area, the City concludes that the plat prospectively prohibits any further development of a structure on the Aerie lot, including the proposed sports court. Aerie concludes, to the contrary, that the building pad plat restriction applies only to the primary structure, and does not proscribe other development activity on the lot.

Our Office is not aware of any Utah appellate decision that directly addresses the proper interpretation of plat notes, specifically. However, Utah recognizes the basic legal concept that when “lands are granted according to an official plat of a survey, the plat itself, with all its notes, lines, descriptions and landmarks, becomes as much a part of the grant or deed by which they are conveyed, and controls so far as limits are concerned, as if such descriptive features were written out on the face of the deed or grant itself.” Barbizon of Utah v. Gen. Oil Co., 24 Utah 2d 321, 323, 471 P.2d 148 (Utah 1970).

As such, Utah Courts construe deeds “like other written instruments, and . . . employ all appropriate tools of construction to arrive at the best interpretation of its language . . . [to] determine the parties' intent from the plain language of the four corners of the deed.” Keith v. Mt. Resorts Dev., L.L.C., 2014 UT 32, ¶ 21. However, a deed is ambiguous “if the parties have both advanced a tenable interpretation of the language,” in which case extrinsic evidence may be used “to illuminate the intent of the parties.” RHN Corp. v. Veibell, 2004 UT 60, ¶ 40. Beyond this, any remaining doubts regarding “uncertain or ambiguous restrictions” are to be resolved “in favor of the free and unrestricted use of property.” Freeman v. Gee, 18 Utah 2d 339, 345, 423 P.2d 155 (Utah 1967).

Here, other than the depicted building pad areas, the plat does not otherwise contain any notes defining building pad and/or limits of disturbance. Therefore, both parties advance tenable interpretations of the subdivision plat’s depiction of “building pad” on the Aerie lot, in that it either means a limitation on all development activity for the lot, or else reflects a limitation on the primary structure only. To resolve this ambiguity, then, both parties urge us to look at the legislative history of the master planned development approval. We agree with this approach that the “legislative history” of the plat—meaning the stated conditions of the master planned development approval itself as well as the applicable land use ordinances in effect at the time—would be appropriate extrinsic evidence to illuminate the intent of the parties to the plat.

The City approved the master planned development on June 17, 1993. A Sketch and Preliminary plat were approved on September 8, 1993, and the final subdivision plat for the Hearthstone Subdivision was later approved on October 7, 1993. A revised plat was later approved on April 21, 1994, which reduced the 12-lot subdivision to ten lots. The revised plat was approved and recorded in June of 1994, and the parties have proffered that the 1994 version of the Land Management Code reflects the relevant version of land use ordinances applicable to the approved subdivision plat that we should consider.

The master planned development conditions of approval stated that the “plat shall contain notes regarding . . . limits of disturbance as specified at the time of final plat approval.” It also stated that “Limitations on landscaping and irrigation shall be defined at the time of final plat,” and further provided that “Structures built in the [subdivision] shall be limited by a maximum house size of up to 6,000 square feet.”

Both parties acknowledge that the final plat approval and subsequently recorded plat did not address any separate limits of disturbance or limits on landscaping. The City concludes that this absence establishes that the “building pad” plat designation is intended as a restriction to limit construction activity on each lot to minimize impact to steep slopes and significant vegetation. Aerie alleges, however, that the master planned development approval contemplated a limit of disturbance to ensure each lot contained opens space, but that by the time of final plat approval, the “plan had changed so that the developer was going to dedicate an entire lot to open space thereby negating the need for open space on each individual lot,” which is alleged to be why the limitation of disturbance was not included on the plat.

We conclude that the building pad depiction on the plat was intended to regulate the construction activity of the primary structure, only, and not to serve as a prospective restriction on further development activity on the rest of the lot for other kinds of lot improvements such as the sports court in question. The applicable regulations at the time did provide a way to clearly impose the kind of prospective development restrictions the City has in mind, but would have employed platted definitions, easements, covenants to more clearly and effectively restrict the proscribed activity. Since these tools were not used, we decline to conclude any such prohibitions now exist.

The 1994 Code provided that “Building sites or envelopes shall be designed which minimize disturbance of existing vegetation. In designating building envelopes, consideration should be given to minimum separations between structures.” Id. § 15.4.2(b) (1994). While the 1994 Code does not have an enacted definition for “building sites” or “building envelope,” it is clear that the code nevertheless adheres to the traditional concept of building envelope and buildable area, in that required yard setbacks establish the total outer limits of where a building “site” or “area” may be built in relation to the lot’s respective property lines. See, “Setback,” id. (“The distance between a building and the street line or road right-of-way, or nearest property line thereto.”); See also, “Yard,” id. (“A required space on a lot other than a court, unoccupied and unobstructed by buildings from the ground upward . . .”) (emphasis added).

The City’s subdivision ordinances at the time provide, for all subdivisions, and not just master planned developments,[1] that “a separate plan which addresses limits of disturbance and vegetation protection during construction and revegetation of disturbed areas will be required.” Id. § 15.4.1(m) (1994) (emphasis added). However, this required disturbance plan does not appear to equate to requiring designations on the plat itself, unless “staff determines that there is significant vegetation on the site or if it is important to clearly designate future building locations,” in which case “Limits of disturbance or building pad lines shall be shown on the preliminary and final plats.” Id. § 15.4.2(d) (1994) (emphasis added). However, the code requires that “Limits of disturbance or building pad lines with definitions as approved by the staff must be reflected on the final plat.” Id. (1994) (emphasis added). Without any accompanying definitions that would have clearly acted as a prospective restriction on any development activity, according to the provisions cited above, we are left to conclude that the intention would have been nothing more than to designate the location of the “Main Building,” See, LMC § 2.1 (1994), in order to protect existing vegetation during construction. Should the intention have been to limit any future development activity beyond the building pad, including for landscaping and other lot improvements, the final subdivision plat requirements direct that any such self-imposed restrictions, reservations, easements, or covenants, should be clearly restricted on the plat. See, id. §§ 15.5.2, 15.5.3, 15.5.4 (1994).

In other words, the 1994 ordinances allowed the City to impose building pad lines as a plat restriction to define a specific building envelope within the total buildable area of the lot as defined by setbacks, if there was a specific need to protect significant vegetation or designate future building locations. Those plat restrictions could have included easements, reservations, covenants, or specific definitions had the intention been for the building pad to include permanent landscaping or improvement restrictions. However, in absence of any specific definition on the plat or explanation of any reservation or easement, the ordinances at the time evidence that the parties’ intention in depicting “building pad” on the 1993 subdivision lots was merely to designate where the principal residential structure should go, and would not have prohibited future development of other lot improvements. See, id. §§ 8.14, 8.15 (1994).

We therefore conclude that whereas no defined development restrictions are reflected on the plat, and in resolving doubts in favor of the free and unrestricted use of property, the “building pad” plat note does not restrict the development of a sports court on the lot areas outside of the building pad area.

II. The Commission’s Finding that the as-built conditions Violated the City’s Steep Slope Regulations is Not Supported by the Record.

The City’s staff report identifies that the Aerie property is subject to the “Sensitive Land Overlay,” or “SLO.” The Code’s “Sensitive Lands Regulations – Slope Protection” provisions state the following prohibition: “No Development is allowed on or within fifty feet (50’), map distance, of Very Steep Slopes.” LMC § 15-2.21-4 (2007).[2]

This is an objective development standard for which noncompliance would be an independent basis for denial. However, we conclude that the Commission’s finding that this provision is violated by the development activity is not supported by the record, as it actively conflicts with the Commission’s other findings that slopes could not be determined without more information on the site’s pre-development condition.

In the City’s final action letter, the very first reason provided as basis for the Commission’s denial is that “The subject property contains Steep Slopes and Very Steep Slopes, which have been disturbed and terraced to accommodate the Recreation Facility.” However, the Commission also found that the submitted slope map and vegetative cover map were reflective of post-development conditions, and that because of this, “staff is unable to verify . . . in what areas development was placed within 50’ of Very Steep Slopes.” The Commission went on to conclude that, according to the post-development conditions slope map, much of the new development is currently within 50’ of Very Steep Slopes.

The Commission’s findings acknowledge that it is the pre-development conditions that would determine compliance with the Code’s regulations on Very Steep Slopes. Indeed, the staff report suggested that the applicant could resubmit by providing additional analysis of pre-development conditions, including identifying areas of Steep Slopes, Very Steep Slopes, and Significant Vegetation. Therefore, the Commission’s finding that Very Steep Slopes have been disturbed is undermined by its other finding that slopes could not be determined, and is therefore not supported by the record.

III. Final Action on Conditional Use Applications Must Be Supported by Substantial Evidence; The Substantive Review Process Allows for Obtaining Additional Necessary Information before Decision-making, and the City’s Code Suggests that the Planning Commission Should Have Continued the Matter per Aerie’s Request

Aerie alleges that the City erred in denying the conditional use permit by finding that it “lacked information to determine compliance with screening and landscaping, lighting, noise, sensitive lands, and steep slope requirements.” Aerie argues that state law requires that in order to deny a conditional use application, the City must (1) make findings of detrimental effects anticipated by the proposed use, and (2) find that the reasonably anticipated detrimental effects “cannot be substantially mitigated by the proposal or the imposition of reasonable conditions to achieve compliance with applicable standards.” See, Utah Code § 10-9a-507(2)(c).

Aerie argues that in denying the application for insufficient information, the City effectively “dodged its duties” to make findings to support either an approval or denial of the conditional use application by substantial evidence.

We note, briefly, that had there been an independent objective basis for denial—such as the violation of plat restrictions on development or noncompliance with some other development standard such as the steep slope regulations—a decision denying the application would not have been in error even without required conditional use findings, because such development restrictions or code compliance issues are not something that can be “mitigated” by condition. However, because we have concluded that the plat imposed no development restriction, and the City’s finding regarding steep slope violations was not supported by the record, the City’s denial must otherwise stand on the basis of its review of the proposed conditional use according to its enacted standards.

Utah law has made clear that the approval or denial of a conditional use application is an administrative decision that must be supported by substantial evidence. McElhaney v. City of Moab, 2017 UT 65, ¶ 27. Substantial evidence requires findings of fact, and the failure to produce findings, generally, is a “fatal flaw” that renders a decision arbitrary and capricious. N. Monticello All. LLC v. San Juan Cty., 2023 UT App 18, ¶ 17. The reason for requiring findings to support an administrative decision is “to permit meaningful appellate review” by “inform[ing] the parties of the basis of the administrative agency’s decision such that the parties knew why the agency ruled the way it did.” Staker v. Town of Springdale, 2020 UT App 174, ¶ 40 (cleaned up).

Here, the City’s denial was, in fact, memorialized in a written final action letter that listed a total of 17 findings of fact. The City’s enacted conditional use standards require the City to conclude that the “Application complies with all requirements of this LMC,” and that the “Use will be Compatible with surrounding Structures in Use, scale, mass, and circulation,” and that “the effects of any differences in Use or scale have been mitigated through careful planning.” LMC § 15-1-10(D). To reach this conclusion, the Code provides a list of 16 items which the City “must review . . . when considering whether or not the proposed Conditional Use mitigates impacts of and addresses the [listed] items.” Id. § 15-1-10(E).

In the final action letter, the Planning Commission found that the application “does not meet Land Management Code, Section 15-1-10, Conditional Use Review Process, due to a lack of information submitted regarding screening and landscaping, compatibility with surrounding structures, potential noise, lighting, environmentally sensitive lands, steep slopes, and appropriateness of the proposed Structure to existing topography of the Site.” (emphasis in original). The City cited to five of the 16 required review criteria it found as having “not been sufficiently addressed”— namely, Subsections (E)(7), (E)(8), (E)(11), (E)(12), and (E)(15). In substance, the Planning Commission is effectively saying: we didn’t have enough information to make the findings we were required to. This is an outcome that should not occur if LUDMA is followed correctly.

LUDMA anticipates that a municipality’s application process for land use approvals will entail “specific, objective, ordinance-based application requirement[s].” See, Utah Code § 10-9a-509.5(1). In which case, the applicant bears the initial burden to present a complete land use application according to the ordinance-based application requirements. However, once an application is submitted, as it is ultimately the land use authority that must support its administrative decision with substantial evidence in the record, the burden effectively shifts to the municipality to ensure it has all of the information needed before it moves that matter forward for decision. Namely, LUDMA explicitly requires a city, upon receiving an application to (1) “in a timely manner,” determine the application is complete, and then (2) substantively review a complete application and approve or deny “with reasonable diligence.” Id. § 10-9a-509.5(1)-(2).

This initial review as to form, and subsequent substantive review, is the process by which a city is able to ensure that there is enough evidence in the record from which to make findings to avoid arbitrary and capricious decisions. It is often the case that an application may be “red-lined” and returned to the applicant with requests for additional or clarifying information, before the application proceeds further. In the separate context of subdivision approval, this back-and-forth process was recently defined in LUDMA as a “review cycle,”[3] in which case there may be several rounds.

Throughout the application process, after the application is submitted, it is generally the city who is at the helm as to whether the application is moving forward; in deeming it complete or sending back to the applicant, and then forwarding it on to the designated land use authority, and scheduling the application as an item on the public agenda for formal consideration and action. In that regard, we generally agree with Aerie’s proposition that a land use authority has not “work[ed] within the statutorily required framework” to the extent that the land use authority has decided to take final action on an application without sufficient information to make required findings.

However, LUDMA does provide a circumstance under which the applicant may take control of whether to move the application forward for final action. After a reasonable period of time to allow the land use authority to consider an application, the applicant may in writing request final action on the application within 45 days from the request. See, Utah Code § 10-9a-509.5(2)(b). If the effect of the request is to cut short any routine review cycle that would otherwise have produced more information for the record, the request under Section 509.5(2)(b) might be appropriately characterized as “proceed at your own risk” when it comes to compelling the land use authority to take final action on an application with only the information submitted to that point. Under those circumstances, we agree that a “lack of information” necessary to support findings required by conditional use standards would be a valid basis for denial. However, we do not feel those circumstances are present here, as although the applicant made an initial demand for final decision, that demand was on a separate land use application and it was ultimately the City who moved forward with final action on this CUP despite the applicant’s request for a continuance.

The staff report for the Aerie application reflects that the applicant did, in fact, make a demand for final action under Section 509.5(2)(b), albeit for the specific Administrative CUP for proposed retaining walls, and not for the Private Recreation Facility CUP. Staff suggested, however, that a decision on the conditional use application for the sports court use was necessary before proceeding further with the other Administrative CUP. At the hearing, in response to a commissioner’s question as to why the retaining wall Administrative CUP would not be heard first, the applicant responded that they wanted it first, but were deferential.

Over the course of the hearing, the general lack of necessary information was discussed, and the applicant expressed its preference for a continuance to provide the information requested. However, the Planning Commission moved forward with its decision to deny.

The Code provides that a public hearing is required for a conditional use application. LMC § 15-1-10(C). The Code also addresses an applicant’s request for continuance for an item scheduled for public hearings, which gives staff the authority to continue if requested five days in advance, or, otherwise, the Planning Commission “will determine if there is a sufficient reason to continue the item on the scheduled date.” Id. § 15-1-12.5.

LUDMA requires a land use authority to make findings of detrimental effects according to its conditional use standards, as well as the potential mitigation of those identified effects by condition. The land use authority must “approve or deny” the application, See Utah Code § 10-9a-509.5(2)(a), and support the decision with substantial evidence in the record. A lack of sufficient information to evaluate the listed items the City “must review” under its conditional use standards, see, LMC § 15-1-10(E), is more than a “sufficient reason to continue” a conditional use matter to avoid arbitrary and capricious decision-making.

We recognize that, apart from insufficient information, the Planning Commission felt it had other independent bases for denial, which may have contributed to its decision not to continue the application for more information. But since we find the Commission’s conclusion regarding plat restrictions to have been in error, then taking final action on the basis of insufficient information, alone, was contrary to both state law and local ordinance that directed that the matter should have been continued.

IV: Remaining Findings According to the City’s Conditional Use Review Must be Revisited to Consider Proper Plat Interpretation and Additional Necessary Information.

Other than the Commission’s findings regarding plat note restrictions, steep slope noncompliance, and insufficient information for five of the 16 required conditional use review criteria, the Commission did make other affirmative findings under its conditional use review criteria to support its denial. For example, the Commission found as follows:

[11]c. The proposed resized sports court adds approximately 2,085 square feet of impervious surfaces to the site. This is not adequately mitigated in the applicant's proposal, as they have only shown new proposed vegetation uphill of the court and proposed to retain a hardscape flagstone patio and artificial turf lawn downhill of the court.

[11]d. The amount of disturbed and landscaped areas outside of the Building Pad is not consistent with other properties in the Overlook at Old Town subdivision. …

-

- The proposal is not consistent with the General Plan, as it allows for disturbance of Sensitive Lands without adequate mitigation.

a. The property is located in the Masonic Hill neighborhood of the General Plan. The property is noted as having slopes that exceed 30 degrees. The General Plan identifies Masonic Hill as a "natural conservation neighborhood", with it also denoted as "Critical Area for Protection and Conservation". The General Plan stresses that, "the aesthetic of the Masonic Hill Neighborhood should be preserved".

b. These elements are described in Goal 4 of the General Plan, Open Space, and Objective 4D emphasizes to minimize further land disturbance and conservation or remaining undisturbed land areas to development to minimize the effects on neighborhoods.

As to finding 16, we note that Aerie’s final contention had been that the Commission improperly relied on aspirational or subjective provisions of the City’s general plan to deny the application. While we ultimately conclude that the Commission’s findings must be revisited, we fundamentally disagree that the Commission’s finding number 16 regarding the general plan, above, is somehow irrelevant or that the Commission “relied” on this finding to support its denial.

The final item on the Code’s listed required review items for conditional use review states “reviewed for consistency with the goals and objectives of the Park City General Plan,” however, the Code itself qualifies this item by further stating that “such review for consistency shall not alone be binding.” LMC § 15-1-10(E)(16). It is clear, then, that this final required review item cannot be used as a sole item of noncompliance to support the denial of a conditional use permit under the Code. We find this to be consistent with state law in that the general plan, as typically expressing a statement of policy, may “provide guidance to the reader as to how the [zoning ordinance] should be enforced and interpreted, but [is not] not a substantive part of the statute.” See, Price Development Co. v. Orem City, 2000 UT 26, ¶ 6. We nevertheless find the review item relevant as framing the nature of the detrimental effects to be found under the Code’s other required review items, as well as providing guidance as to what conditions may or may not be considered reasonable to achieve compliance with the Code’s stated goals and requirements.

The problem here, however, is the relation of the Code’s required review items to the Commission’s findings that it had insufficient information to determine compliance. We find that each of these remaining findings, 11(c), 11(d), 16(a), and 16(b), all suffer, to some extent, on the erroneous findings discussed herein, or to the Commission’s other findings that it had insufficient information to determine compliance, and should be revisited on the premise that plat does not restrict development activity of a sports court outside of the building pad, and only after receiving additional information regarding the pre-development condition of the property in order to determine the actual impacts of the previous land disturbance and development activity, as proposed.

For example, 11(c) and 11(d)’s findings that the proposal adds additional impervious surface without adequate mitigation and that the amount of disturbed and landscaped areas outside of the Building Pad is inconsist with other properties in the subdivision, both appear to relate to required review items that the Commission already found were lacking in information to determine compliance, such items (E)(8), “Building mass, bulk, and orientation, and the location of Buildings on the Site; including orientation to Buildings on adjoining Lots,” item (E)(11), “physical design and Compatibility with surrounding Structures in mass, scale, style, design, and architectural detailing,” and item (E)(15), “within and adjoining the Site, Environmental Sensitive Lands, Physical Mine Hazards, Historic Mine Waste and Park City Soils Ordinance, Steep Slopes, and appropriateness of the proposed Structure to the existing topography of the Site.” LMC § 15-1-10(E). The same can also be said for the findings under 16(a) and 16(b).

In other words, these remaining findings—similar to the findings on steep slopes—are undermined by the Commission’s other findings that it had insufficient information to determine compliance. The Commission must make findings that are definitive and based upon adequate information. Therefore, the Commission should revisit its findings with the proper legal analysis and upon the additional information identified as necessary for determining compliance.

We note, finally, that the Staff had signaled to the Commission that, even with additional information, a denial might still be recommended due to questions of whether the applicant could adequately mitigate the loss of vegetation and issues of drainage due to the amount of impervious surface and other landscaping added. That may very well continue to be the case once the Commission reviews the application upon proper supporting information, however, the Commission must nevertheless make the attempt, and definitively support its findings upon proper information, which includes not only findings of detrimental effects according to its standards, but also specific findings as to whether “reasonable conditions are proposed, or can be imposed, to mitigate” those effects to achieve compliance. Utah Code § 10-9a-507(2)(a) (emphasis added).

Conclusion

The Planning Commission’s basis for denying Aerie’s conditional use application because it determined that the plat prohibited further development on the lot was in error. The Commission further erred by taking final action to deny the application due to lack of sufficient information when the applicant had requested a continuance to provide additional information requested by Staff and the Commission. The Planning Commission should reconsider the application in light of a proper interpretation of the plat, and upon receiving the additional information identified as necessary in order to make required findings according to the City’s conditional use review process. This must not only include findings of reasonably anticipated detrimental effects, but also findings as to whether those effects can be substantially mitigated by reasonable conditions to achieve compliance with the City’s enacted standards.

...

...

Jordan S. Cullimore, Lead Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

...

NOTE:

This is an advisory opinion as defined in Section 13-43-205 of the Utah Code. It does not constitute legal advice, and is not to be construed as reflecting the opinions or policy of the State of Utah or the Department of Commerce. The opinions expressed are arrived at based on a summary review of the factual situation involved in this specific matter, and may or may not reflect the opinion that might be expressed in another matter where the facts and circumstances are different or where the relevant law may have changed.

While the author is an attorney and has prepared this opinion in light of his understanding of the relevant law, he does not represent anyone involved in this matter. Anyone with an interest in these issues who must protect that interest should seek the advice of his or her own legal counsel and not rely on this document as a definitive statement of how to protect or advance his interest.

An advisory opinion issued by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman is not binding on any party to a dispute involving land use law. If the same issue that is the subject of an advisory opinion is listed as a cause of action in litigation, and that cause of action is litigated on the same facts and circumstances and is resolved consistent with the advisory opinion, the substantially prevailing party on that cause of action may collect reasonable attorney fees and court costs pertaining to the development of that cause of action from the date of the delivery of the advisory opinion to the date of the court’s resolution. Additionally, a civil penalty may also be available if the court finds that the opposing party—if either a land use applicant or a government entity—knowingly and intentionally violated the law governing that cause of action.

Evidence of a review by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman and the opinions, writings, findings, and determinations of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman are not admissible as evidence in a judicial action, except in small claims court, a judicial review of arbitration, or in determining costs and legal fees as explained above.

The Advisory Opinion process is an alternative dispute resolution process. Advisory Opinions are intended to assist parties to resolve disputes and avoid litigation. All of the statutory procedures in place for Advisory Opinions, as well as the internal policies of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman, are designed to maximize the opportunity to resolve disputes in a friendly and mutually beneficial manner. The Advisory Opinion attorney fees and civil penalty provisions, found in Section 13-43-206 of the Utah Code, are also designed to encourage dispute resolution. By statute they are awarded in very narrow circumstances, and even if those circumstances are met, the judge maintains discretion regarding whether to award them.

...

Endnotes

_________________________________________________

[1] The code’s master plan development provisions simply repeat these same standards—applicable to all subdivisions—to master planned developments, without any significant alteration. See, LMC § 10.9(k) (1994).

[2] We note that since the time of Aerie’s application, this section has more recently been amended. We therefore cite to the last version of this section of the LMC that was in effect at the time of application.

[3] Section 10-9a-604.2 provides that, as used in that section: “‘Review cycle’ means the occurrence of:

(i) the applicant's submittal of a complete subdivision land use application;

(ii) the municipality's review of that subdivision land use application;

(iii) the municipality's response to that subdivision land use application, in accordance with this section; and

(iv) the applicant's reply to the municipality's response that addresses each of the municipality's required modifications or requests for additional information.”