Advisory Opinion 269

Parties: Blaine K. Andersen; Hyrum City

Issued: June 6, 2023

...

Topic Categories:

TOPIC CATEGORIES:

Compliance with Land Use Regulations

Requirements Imposed on Development

Subdivision Plat Approval

State law requirements that cities provide notice of subdivision applications to certain nearby water conveyance facility owners to solicit feedback does not mandate that the subdivision approval be conditioned according to that feedback.

Hyrum City provided notice of a proposed subdivision to an irrigation company that operates a ditch on the subdivision property by longstanding prescriptive use. At the request of the irrigation company, the city imposed a requirement that the subdivision applicant dedicate an easement for access to the ditch across the subdivision property in favor of irrigation company.

State law does not allow the city to impose this condition as requested by the irrigation company because it is not expressed in either state code, or Hyrum City ordinance. The City must approve a subdivision plat that conforms with its enacted standards, and therefore may not require the applicant to provide, as a condition of subdivision approval, a dedicated access easement to the irrigation company.

DISCLAIMER

The Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman makes every effort to ensure that the legal analysis of each Advisory Opinion is based on a correct application of statutes and cases in existence when the Opinion was prepared. Over time, however, the analysis of an Advisory Opinion may be altered because of statutory changes or new interpretations issued by appellate courts. Readers should be advised that Advisory Opinions provide general guidance and information on legal protections afforded to private property, but an Opinion should not be considered legal advice. Specific questions should be directed to an attorney to be analyzed according to current laws.

Advisory Opinion

Advisory Opinion Requested by:

Local Government Entity:

Applicant for Land Use Approval:

Type of Property:

Residential

Opinion Authored By:

Richard B. Plehn, Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

Issues

Can the city require a subdivision applicant to provide a dedicated access easement to an irrigation company that operates a ditch on the property by prescriptive use?

Summary of Advisory Opinion

State law requires a city to provide notice of a subdivision application to certain nearby water conveyance facility owners to receive comments from facility owners on defined issues; however, it does not mandate that municipalities condition subdivision approval according to that feedback. The status as an easement holder may give a facility owner the right to use property, but does not give it authority to impose land use restrictions on property it does not own. Rather, cities establish their own standards as to what information is required for subdivision approval, or who must sign or authorize subdivision plats, and may not otherwise impose requirements or conditions not expressed in state code or local ordinance.

Hyrum City provided notice of a proposed subdivision to an irrigation company that operates a ditch on the subdivision property by longstanding prescriptive use. At the request of the irrigation company, the city imposed a requirement that the subdivision applicant dedicate an easement for access to the ditch across the subdivision property in favor of irrigation company. State law does not allow the city to impose this condition as requested by the irrigation company because it is not expressed in either state code, or Hyrum City ordinance. Therefore, the City may not require the applicant to provide, as a condition of subdivision approval, a dedicated access easement to an irrigation company that operates a ditch on the property by prescriptive use.

Evidence

The Ombudsman’s Office reviewed the following relevant documents and information prior to completing this Advisory Opinion:

- Request for Advisory Opinion submitted by Blaine K. Andersen, received on November 2, 2022.

- Letter from Matthew Holmes, on behalf of the City of Hyrum, on November 9, 2022.

- Email from Blaine K. Andersen, on November 10, 2022.

- Email from Matthew Holmes on November 18, 2022, with attached letter from Hyrum Irrigation Company, dated November 10, 2022.

Background

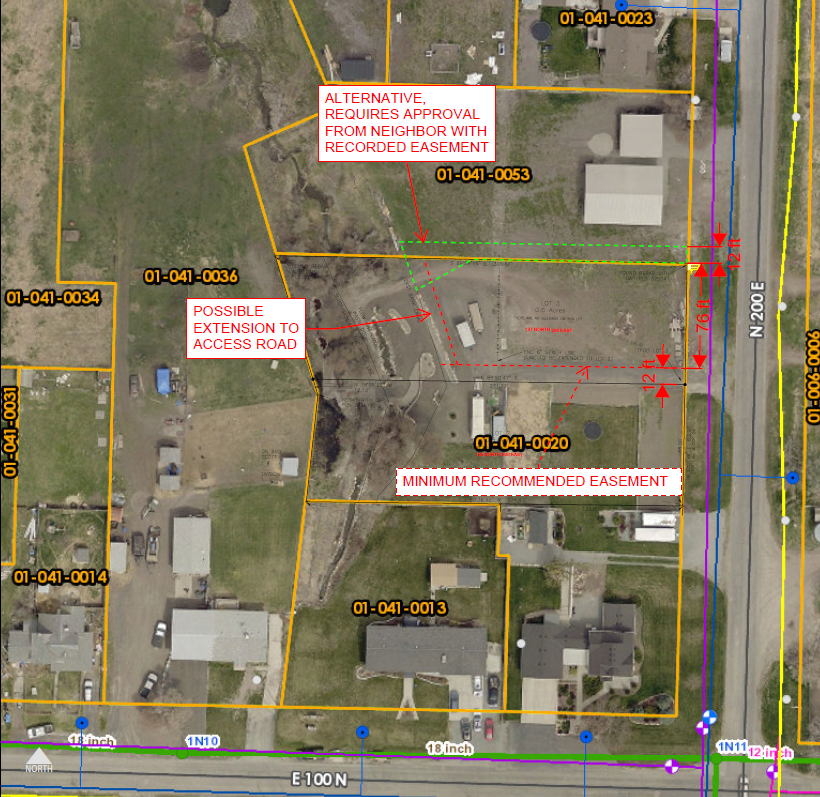

Blaine K. Andersen applied to the City of Hyrum (“City”) for approval of a mini-subdivision pursuant to the City’s ordinances (3 lots or less). According to submitted plans, Mr. Andersen’s property, parcel no. 01-041-0020, is an irregularly shaped corner tract bounded on the east by the north/south-running road 200 E, and to the south by east/west-running 100 N. (see, parcel overview at the end of this section)[1]. An existing home is situated on the southeast corner of the parcel, and Mr. Andersen has proposed subdividing the portion of property with the existing home as a lot, together with the creation of two additional lots from the larger, unimproved portion of the property north of the home, that will have frontage on 200 E.

Hyrum Irrigation Company (“Irrigation Company”) operates a drainage and waste ditch that runs in a northerly direction through the middle of the block between 100 East and 200 East, and includes the western part of the unimproved portion of Mr. Andersen’s property, which would essentially be the “back” of the proposed Lots 2 and 3, in relation to their frontage on 200 East. The parties appear to agree that Irrigation Company has a prescriptive easement for the ditch dating back to when the irrigation company was incorporated in 1933, though Mr. Andersen alleges that Irrigation Company has never used his property to access to the ditch since 1933.

Upon receiving Mr. Andersen’s subdivision application, Hyrum City provided notice of the application to Irrigation Company. After a site visit to the property by City and Irrigation Company officials to observe the ditch and terrain surrounding the facility, the Hyrum City Planning Commission imposed a condition on Mr. Andersen’s subdivision approval that he grant Irrigation Company—at Irrigation Company’s request—a utility easement wide enough for a backhoe to access the area for maintenance purposes. The proposed easement would provide access from 200 E, and encumber proposed Lot 3 along the shared east/west boundary with proposed Lot 2 (as indicated in red on the parcel overview, below). Irrigation Company states that it mandates that all property with a prescriptive easement must record a dedicated easement upon development of the property to allow the company to maintain the ditch and to “ensure existing and future property owners understand Hyrum Irrigation’s easement.”[2]

Mr. Andersen opposed the condition, stating his belief that the lots are too narrow for an easement and that access should instead be placed on neighboring property to the north or southwest. The City notes that access via other properties would require approval from those owners, and that as to any north/south access to the ditch from either 100 North or 200 North, the steep slopes of the ditch made this unfeasible (which is disputed by Mr. Andersen). However, the City has since provided a suggested alternative easement over neighboring property in response to Mr. Andersen’s objection (as indicated in green on the parcel overview, below), that the City would accept, assuming Mr. Andersen can work out an agreement with the other affected property owner.

City Code allows the City Administrator, Recorder, and Zoning Administrator to grant administrative approval without City Council approval by signing a waiver. The City will not approve the subdivision administratively by waiver without the proposed easement, but has informed Mr. Andersen that he could submit this matter to the City Council for review, if desired.

Mr. Andersen has requested an Advisory Opinion to determine whether the City has the authority to impose the requirement to grant an easement to Irrigation Company as a condition of his development approval.

Analysis

The interests of landowners and water facility owners have long been in tension in the land use development process, with the local land use authority often put in the middle. In recent years, the Utah legislature has added certain processes to state statutes aimed at allowing conflicts between landowners and water facility owners a better chance of being resolved before a development approval must be decided by a municipality.[3]

However, when disputed property interests are brought forward during a city’s review of land use application, it is not the city’s role to resolve those competing interests on an ad-hoc basis during an administrative approval process. Cities may plan ahead of such a situation by enacting land use regulations that require a certain level of proof or affirmative consent of defined, undisputed interest holders before an approval may be given.

In the end, however, a city must take an application on the good faith representations of the applicant, and take action to approve or deny the application according to enacted standards only. If a land use applicant interferes with other private property interests, those competing interests may be enforced or adjudicated by the court, the only entity having authority to quiet title to property.

In imposing the dedicated easement condition as requested by the irrigation company, the City responds that it has simply followed state law to the best of its understanding. However, Utah’s Land Use, Development, and Management Act (“LUDMA”), as applied to municipalities, provides that a “municipality may not impose on an applicant . . . a requirement that is not expressed in: (i) this chapter [LUDMA]; (ii) a municipal ordinance; or (iii) a municipal specification for public improvements applicable to a subdivision or development that is in effect on the date that the applicant submits an application.” Utah Code § 10-9a-509(1)(f).

As will be discussed below, Hyrum Irrigation Company’s status as an easement holder does not entitle it to impose land use restrictions on the subdivision property, and the City’s condition is not otherwise expressly provided by either LUDMA or city ordinance. Therefore, the City may not condition subdivision approval on Mr. Andersen conveying an access easement to Hyrum Irrigation Company.

I. Section 603 of LUDMA Requires Only that Facility Owners Have an Opportunity to Comment on Proposed Subdivisions, but the City must nevertheless approve a subdivision plat that complies with its enacted ordinances.

The City cites to Section 603 of LUDMA as the basis for imposing the condition. Section 603 requires several things when land is to be subdivided. First, a subdivision applicant must provide the city with certain information about existing easements for underground or water conveyance facilities located within the proposed subdivision plat, both those that are recorded easements, as well as unrecorded facilities of which the property owner “has actual or constructive knowledge.” Id. § 10-9a-603(2)(f).

In turn, within 20 days of receiving a subdivision application, the city must provide notice of the application to any facility owner of a water conveyance facility located within 100 feet of the subdivision plat, and must hold the application for at least 20 days in order to receive comments from facility owners on:

(A) access to the water conveyance facility;

(B) maintenance of the water conveyance facility;

(C) protection of the water conveyance facility;

(D) safety of the water conveyance facility; or

(E) any other issue related to water conveyance facility operations.

Id. § 10-9a-603(3)(d)(ii). Citing to this section, the City has determined that the irrigation company meets the definition of a facility owner, and the drainage and waste ditch running through Mr. Andersen’s subdivision meets the definition of a water conveyance facility; therefore, the City argues, because Irrigation Company’s request meets the condition allowed by state law and complies with the same, the requirement was imposed by the Hyrum City Planning Commission.

However, these provisions do not require anything more than simply providing notice to, and soliciting feedback from, facility owners. Whether or not the city receives the solicited feedback, Section 603 provides that “if the plat conforms to the city’s ordinances and this part and has been approved by the culinary water authority, the sanitary sewer authority, and the local health department . . . the municipality shall approve the plat.” Id. § 10-9a-603(3)(a).

To that point, however, Section 603 does provide that a city “may not require that the plat be approved or signed by a person or entity who . . . does not . . . have a legal or equitable interest in the property within the proposed subdivision.” Id. § 10-9a-603(3)(c). The corollary of this is that the City may choose to require plat approval of someone having a legal or equitable interest—such as an easement—in the subdivision property. As stated, however, as a plat must be approved if it conforms to the City’s ordinances, this requirement for plat approval by other interest holders must be stated in the City’s enacted ordinances.

Consistent with Section 603, the City’s subdivision ordinances require the subdivision applicant, as part of a proposed preliminary plat, to show “[e]xisting ditches, canals, natural drainage channels, open waterways, and proposed alignments within the tract and to a distance of at least 100 feet beyond the tract boundaries.” Hyrum City Municipal Code (“City Code”) § 16.12.030.B. The applicant must also provide a “written statement from the appropriate agency (such as irrigation companies, private land owners, etc.) regarding the effect of the proposed subdivision on any irrigation channels or ditches and any piping or other mitigation required.” Id. § 16.12.030.D.

Similar to LUDMA’s provisions, however, while the City’s ordinances require such a statement from potentially affected irrigation companies, the language does not affirmatively require that entity’s approval or signature of the plat. Rather, a final plat must contain approval blocks for: (1) the surveyor; (2) the owner; (3) a notary; (4) the City Engineer; (5) the Mayor; (6) Hyrum City Culinary Water and Hyrum City Sanitary Sewer authorities; (7) “all other utility companies servicing the development”; and (8) the County Recorder. Id.§ 16.12.030.C. (emphasis added).

The City reads LUDMA’s Section 603 as either requiring, or, at the very least, authorizing, its imposition of a condition to convey an easement to a facility owner according to the feedback received from that affected facility owner. However, we do not find that authorization in the language. Rather, state law requires that notice be given to facility owners, and an opportunity to comment, but directs that subdivisions should be approved according to the requirements found in local land use ordinances. The City, through its enacted subdivision ordinances, could require plat approval by those holding an easement in the property to be subdivided.[4] Hyrum City ordinances require written statement regarding the subdivision’s effect on irrigation channels or ditches, but does not make the consent of Irrigation Company a factor for approval.

II. Utah’s Water Conveyance Facility Relocation Statute Cannot be Used to Affirmatively Impose Required Modifications as a Condition of Approval

One additional provision of Section 603 that the City cites to states that “[w]hen applicable, the owner of the land seeking subdivision plat approval shall comply with [Utah Code] Section 73-1-15.5.” Utah Code § 10-9a-603(3)(e). The purpose of Section 73-1-15.5, as provided by its statutory title, is for the “[r]elocation of easements for a water conveyance facility,” or “[a]lteration of a water conveyance facility.” Id. § 73-1-15.5.[5]

This statute, enacted in 2018,[6] provides a process in which “a property owner may make reasonable changes in the location and method of delivery of a water conveyance facility located on the property owner’s real property,” as long as the modification will not “significantly decrease[] the utility of the water conveyance facility for its current use . . . increase the burden on the facility owner,” or “frustrate[] the purpose of the water conveyance facility.” Id. § 73-1-15.5(2),(4). In proposing to relocate or change a water facility, the landowner must also “provid[e] the facility owner with the ability to reasonably access, operate, maintain, and replace the modified water conveyance facility.” Id. § 73-1-15.5(2)(e).

In other words, where a subdivision applicant proposes development that will clearly conflict with a water conveyance facility in the property, it is incumbent on the landowner to first have complied with this statutory process that allows the landowner to relocate or make reasonable changes to a water facility in a way that won’t unreasonably interfere with established rights.

The City cites to Section 603’s reference to complying with the water facility relocation statute, and argues that the statute provides that if a request is reasonable, it shall be granted by the subdivider. Based on this, the City argues, Irrigation Company can request the easement condition for maintenance purposes. However, the process created by the relocation statute is not a basis for imposing conditions on the subdivision applicant.

The water facility relocation statute creates a process that is initiated by the property owner. See, id. § 73-1-15.5(2) (“a property owner may make reasonable changes . . . .”). It is only in response to a property owner’s proposed modification that a facility owner may then “require a change to the plans” to protect its rights. Id. § 73-1-15.5(2) (emphasis added). The statute does not authorize a facility owner to initiate water facility modifications that a property owner must agree to, as suggested by the City.

Section 603’s reference to compliance with the water facility relocation statute could not be used, then, to affirmatively condition approval of a subdivision application that imposes some required modification or relocation of a water conveyance facility that had not been initiated and engineered by the property owner according to Section 73-1-15.5. See, id. § 10-9a-509(1)(f) (a municipality may not impose on an applicant a requirement that is not expressed in “(i) this chapter [LUDMA]; (ii) a municipal ordinance; or (iii) a municipal specification for public improvements . . . .”).

Mr. Andersen alleges that he is not proposing to change either the “location” or “method of deliver of water” of the existing ditch. See, id. § 73-1-15.5(2). Rather, Mr. Andersen alleges that the ditch will remain the same, and he appears to be arguing, essentially, that the Irrigation Company’s concern is simply one of additional access beyond the existing rights Irrigation Company may have by prescriptive use—in Mr. Andersen’s view—and the indirect effect that this lack of additional access, as desired, may have on the practicality of ongoing maintenance of the ditch.

The problem here, then, is that the disputed nature of the scope and/or nature of Irrigation Company’s prescriptive easement does not lend itself to a determination that Section 73-1-15.5 applies, or has not been complied with by the applicant. It therefore is not applicable as a basis for imposing conditions on the subdivision application.

III. The Irrigation Company’s Authority Over the Property is Limited to its Existing Easement Rights, the Scope of Which is Disputed

At common law, an easement is a nonpossessory interest in land owned by another person, consisting in the right to use or control the land, or an area above or below it, for a specific limited purpose; the one benefiting from the easement is known as the dominant estate, and the land burdened by the easement is the servient estate.[7]

The parties agree that Hyrum Irrigation Company, having operated an overflow ditch through Mr. Andersen’s property since its incorporation in 1933, has an established prescriptive easement for the ditch. See, Utah Code § 57-13a-102 (providing that a prescriptive easement is established if a water user has maintained a water conveyance for a period of 20 years during which the use has been continuous, open and notorious, and adverse[8]).

The Irrigation Company states that it “mandates that all property with a prescriptive easement must record a dedicated easement upon development of the property,” and that here, it “requires a dedicated easement to maintain the overflow ditch and to ensure existing and future property owners understand Hyrum Irrigation’s easement.”[9] It is unclear from the Irrigation Company’s letter whether it is asserting that it has the right to demand the access easement in this case by virtue of its existing, established prescriptive rights, or from some other authority to regulate the land use of the property or obtain the desired access.[10]

A. The existing prescriptive easement is disputed as to its purpose, nature, and extent

An easement holder has no authority to enact or demand land use regulations on property, though it may, pursuant to its easement rights, seek to restrict the servient estate holder from unreasonably interfering with the easement. See, Metro. Water Dist. of Salt Lake & Sandy v. SHCH Alaska Tr., 2019 UT 62, ¶ 50 (holding that a water district’s authority over a property did not extend beyond its ability to exercise its easement rights, and that the district did not possess general authority to impose land use regulations on the owner’s property); see also, N. Union Canal Co. v. Newell, 550 P.2d 178, 180 (Utah 1976) (explaining that the land owner over which a canal easement passed did not need to obtain permission from the canal easement holder before placing a fence across the property as long as the fence did not “unreasonably restrict or interfere with the proper use of the plaintiff's easement.”).

It is well-established “that the owner of the servient estate may use his property in any manner and for any purpose consistent with the rights of the owner of the dominant estate, and although the owner of the dominant estate may enjoy to the fullest extent the rights conferred by his easement, [the dominant estate] may not alter its character so as to further burden or increase the restriction upon the servient estate.” Metro. Water Dist. of Salt Lake & Sandy v. SHCH Alaska Tr., 2019 UT 62, ¶ 24 (internal citations omitted).

In other words, neither the underlying landowner nor the easement holder may interfere with the other’s rights in the property. Id., at ¶ 1. However, an easement acquired by prescription is always limited by the use made during the prescriptive period, Salisbury v. Rockport Irr. Co., 79 Utah 398, 7 P.2d 291 (Utah 1932), and is defined generally by its type—based on the purpose for which it was acquired—as well as specifically by scope—based on the nature and extent of the easement’s historical use. SRB Investment Co. v. Spencer, 2020 UT 23, ¶ 14.

Here, none of the parties have explained what they believe to be the type or scope of the irrigation company’s historical use of Mr. Andersen’s property during the prescriptive period (as of 1933), though Mr. Andersen appears to contend that the Irrigation Company has never actually established any use of his property to access the ditch by any defined route.[11] The specific scope of Irrigation Company’s prescriptive easement rights to the property, then, are disputed, and could appropriately be resolved through a quiet title action where necessary.

B. The Irrigation Company’s role in the land use approval process is defined by ordinance.

It is not role of the Ombudsman’s Office to opine on the scope or nature of Irrigation Company’s easement; rather, this advisory opinion is limited to whether the City’s actions are taken under proper authority. It is also not the role of the City to resolve disputed third-party property interests or rights to land in the administrative land use approval process. The City has been delegated the authority to plan ahead of such disputes by enacting various kinds of rules or regulations that might require certain information from an applicant or impose a particular process that ensures other property interest holders have been considered. See, Utah Code §§ 10-9a-102(1)(i), (2)(o) (to accomplish LUDMA’s purposes, including “provid[ing] fundamental fairness in land use regulations,” a municipality may enact ordinances or rules that govern “considerations of surrounding land uses to balance [such] purposes with a landowner's private property interests and associated statutory and constitutional protections.”).

The Irrigation Company’s status as an easement holder does not give it authority to dictate the terms upon which Mr. Andersen, the owner of the underlying land, may use the property, see Metro Water Dist., at ¶ 23; it may not promulgate its own rules and policies so as to constitute land use regulations on proposed development—an authority the legislature intended to be limited to only the legislative bodies of cities and counties. See, id., at ¶¶ 33, 50.

As discussed, City Code appears to limit this to providing a “written statement . . . regarding the effect of the proposed subdivision on any irrigation channels or ditches and any piping or other mitigation required,” City Code § 16.12.030.D, though not requiring that “the plat be approved or signed” by any person or entity with a “legal or equitable interest in the property within the proposed subdivision,” Utah Code § 10-9a-603(3)(c), apart from the applicant itself.

The Irrigation Company could lobby the City to enact standards requiring the signatures of easement holders on the plat in the future, but the current administrative land use approval process does not require it.

After all the required notice, written statements, and other information has been properly produced and considered, the City’s ordinances simply do not allow Irrigation Company to dictate the outcome of a land use approval where the applicant disputes that any rights are affected by the proposal, and the application otherwise complies with the City’s enacted standards.

IV. The Role of the City’s Land Use Authority

The City must substantively review a land use application and “apply the plain language of [its] land use regulations.” Id. § 10-9a-306(1). “[I]f the application conforms to the requirements of the applicable land use regulations, land use decisions, and development standards,” it is entitled to approval” Id. § 10-9a-509(1)(a)(ii). Said again a second time in LUDMA, if a subdivision plat “conforms to the municipality’s ordinances and this part and has been approved by the culinary water authority, the sanitary sewer authority, and the local health department . . . the municipality shall approve the plat.” Id. § 10-9a-603(3)(a).

The City may not impose on Mr. Andersen a requirement to convey an access easement to Irrigation Company because such a requirement is not expressed in Section 603 of LUDMA, Section 73-1-15.5, or in Hyrum City Code. Utah Code § 10-9a-509(1)(f). Beyond this, the administrative land use approval process is not the appropriate venue to quiet title to the Irrigation Company’s prescriptive easement.[12] Therefore, Mr. Andersen is entitled to final action on the application as it has been proposed, and it is incumbent on the City to “approve or deny” the application with reasonable diligence. Id. § 10-9a-509.5(2).

Conclusion

To comply with state law, the City may not require the subdivision applicant to provide the irrigation company with an easement at the company’s request, as the City’s ordinances limit the irrigation company’s role to providing a written statement about the effect of the proposed subdivision, only. The irrigation company’s right to the subdivision property is by prescriptive use, the scope and nature of which are not settled and disputed by the parties. Because the applicant asserts that the proposed subdivision does not interfere with the irrigation company’s prescriptive easement, as established, and no evidence has been presented to the contrary, the City’s role in reviewing the subdivision application is to take final action to approve or deny the application according to the application’s compliance with enacted standards.

...

...

Jordan S. Cullimore, Lead Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

...

NOTE:

This is an advisory opinion as defined in Section 13-43-205 of the Utah Code. It does not constitute legal advice, and is not to be construed as reflecting the opinions or policy of the State of Utah or the Department of Commerce. The opinions expressed are arrived at based on a summary review of the factual situation involved in this specific matter, and may or may not reflect the opinion that might be expressed in another matter where the facts and circumstances are different or where the relevant law may have changed.

While the author is an attorney and has prepared this opinion in light of his understanding of the relevant law, he does not represent anyone involved in this matter. Anyone with an interest in these issues who must protect that interest should seek the advice of his or her own legal counsel and not rely on this document as a definitive statement of how to protect or advance his interest.

An advisory opinion issued by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman is not binding on any party to a dispute involving land use law. If the same issue that is the subject of an advisory opinion is listed as a cause of action in litigation, and that cause of action is litigated on the same facts and circumstances and is resolved consistent with the advisory opinion, the substantially prevailing party on that cause of action may collect reasonable attorney fees and court costs pertaining to the development of that cause of action from the date of the delivery of the advisory opinion to the date of the court’s resolution. Additionally, a civil penalty may also be available if the court finds that the opposing party—if either a land use applicant or a government entity—knowingly and intentionally violated the law governing that cause of action.

Evidence of a review by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman and the opinions, writings, findings, and determinations of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman are not admissible as evidence in a judicial action, except in small claims court, a judicial review of arbitration, or in determining costs and legal fees as explained above.

The Advisory Opinion process is an alternative dispute resolution process. Advisory Opinions are intended to assist parties to resolve disputes and avoid litigation. All of the statutory procedures in place for Advisory Opinions, as well as the internal policies of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman, are designed to maximize the opportunity to resolve disputes in a friendly and mutually beneficial manner. The Advisory Opinion attorney fees and civil penalty provisions, found in Section 13-43-206 of the Utah Code, are also designed to encourage dispute resolution. By statute they are awarded in very narrow circumstances, and even if those circumstances are met, the judge maintains discretion regarding whether to award them.

...

Endnotes

_______________________________________________

[1] Provided in a submission from the City. Email from Matthew Holmes on November 18, 2022.

[2] Letter from Hyrum Irrigation Company re: Advisory Opinion Request, dated November 10, 2022.

[3] Namely, the enactment of a water facility relocation and modification statute in 2018, see Ut. SB 96 (2018), and the later amendments to subdivision plat procedures to require compliance with this relocation statute when applicable, see Ut. HB 315 (2019), as well to extend subdivision notice and feedback requirements to unrecorded water conveyance facilities. Ut. HB 107 (2021).

[4] To be supportable, however, this would likely have to be limited to recorded easement holders or other undisputed property interests. The often-undefined nature of prescriptive easements, as is partly at issue here, may result in an approval requirement that causes more problems than it solves, as every land use application would turn into a quiet title dispute.

[5] Note that Utah courts have held that the title of a statute is not part of the text of a statute, and absent ambiguity, it is generally not used to determine a statute's intent. Jensen v. Intermountain Healthcare, Inc., 2018 UT 27, ¶ 29; see also, Price Development Co. v. Orem City, 2000 UT 26, ¶ 23 (discussing the role of legislative statements of purpose as opposed to operative provisions).

[6] Ut. SB 96, “Canal Amendments” (2018).

[7] Black’s Law Dictionary 622 (10th ed. 2014).

[8] While also presuming that if both the continuous and open/notorious elements are met, there is a rebuttable presumption that the use has been adverse. See, Utah Code § 57-13a-102(2).

[9] Hyrum Irrigation Company letter (November 10, 2022).

[10] For example, Utah law allows private actors to exercise eminent domain in limited circumstances to acquire a “right of way,” (read, easement) over private land for various water-facility related purposes. See, Utah Code § 73-1-6.

[11] Establishing a prescriptive right for access presumes a distinct path or route over the servient estate during the prescriptive period; if several paths were used, each distinct route must be evaluated individually, on its own merits, to create a prescriptive easement. M.N.V. Holdings LC v. 200 S. LLC, 2021 UT App 76, ¶ 17. It at least seems apparent that requesting an access easement along the artificial lot lines imagined by Mr. Andersen in his proposed subdivision is not highly likely to be reflective of any distinct historical route.

[12] Other than applying the plain language of the LUDMA sections cited herein, Utah law has not directly commented on a municipality’s obligation to consider private property disputes raised in response to a land use proposal, but this concept that the land use approval process is not the appropriate venue for quiet title claims has been well articulated in some other states. See, e.g., Borough of Braddock v. Allegheny County Planning Department, 687 A.2d 407 (Pa. Cmwlth. 1996) (a zoning board is an inappropriate vehicle to deal with complex issues of title, which the opposing parties should resolve by a quiet title action); see also, Cybulski v. Planning & Zoning Comm'n, 43 Conn. App. 105, 110, 682 A.2d 1073, 1076 (1996) (planning commission does not have the authority to determine whether a claimed right-of-way is a public highway, since that conclusion can be made only by a judicial authority in a quiet title action).