Advisory Opinion 264

Parties: Jerry Carroll / Spanish Fork City

Issued: December 31, 2022

...

Topic Categories:

Exactions on Development

A city may not impose an exaction requiring a property owner to improve and dedicate private property for some future public use as a condition of development approval when such future use is not occasioned by the development sought to be permitted. Conditions imposed on bargained-for approvals under certain incentive or bonus zoning schemes must still comply with exaction standards. The government cannot withhold even discretionary benefits upon unconstitutional conditions, and a property owner’s refusal to adhere to an illegal exaction cannot be the basis for denial.

The City’s proposed condition that an applicant adding a row of homes to an existing Master Planned Development (MPD) subdivision provide a stub road across their property to dead-end at undeveloped land off-site is an illegal exaction because it is intended to solve a speculative circulation problem that does not yet exist, and is unrelated to the impact of this specific subdivision amendment. The city may not require this as a condition of MPD approval, nor deny the MPD based solely on the property owner’s refusal to agree. Rather, the City must review the application according to its MPD standards and make an ordinance-based administrative decision supported by substantial evidence.

DISCLAIMER

The Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman makes every effort to ensure that the legal analysis of each Advisory Opinion is based on a correct application of statutes and cases in existence when the Opinion was prepared. Over time, however, the analysis of an Advisory Opinion may be altered because of statutory changes or new interpretations issued by appellate courts. Readers should be advised that Advisory Opinions provide general guidance and information on legal protections afforded to private property, but an Opinion should not be considered legal advice. Specific questions should be directed to an attorney to be analyzed according to current laws.

Advisory Opinion

Advisory Opinion Requested by:

Local Government Entity:

Applicant for Land Use Approval:

Type of Property:

Residential

Opinion Authored By:

Richard B. Plehn, Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

Issues

Where a subdivision applicant proposes dividing his property by adding several lots to an existing Master Planned Development, may the city require that the applicant provide a stubbed public street across the subdivider’s property to adjacent, undeveloped land?

Summary of Advisory Opinion

A city may not impose an exaction requiring a property owner to improve and dedicate private property for some future public use as a condition of development approval when such future use is not occasioned by the development sought to be permitted.

Certain incentive or bonus zoning schemes—such as Master Planned Developments—provide discretionary benefits above conventional development standards that a subdivider may choose to avail itself of, but such bargained-for approvals are still subject to the constitutional limitations on development exactions. The government cannot withhold even discretionary benefits upon unconstitutional conditions, and notwithstanding a city’s legitimate use of discretion to otherwise deny a proposed incentive development type according to its enacted standards, a property owner’s refusal to adhere to an illegal exaction cannot be the basis for denial.

The applicant has proposed subdividing his property as an amendment to an existing MPD subdivision, adding a single row of lots to front on the improved road of the MPD subdivision. On review, the City has proposed that the applicant install a continuation of an existing street from the MPD subdivision across the applicant’s property to terminate at undeveloped land off-site, to which the owner disagrees.

Requiring this applicant to provide a stub road to off-site land for future development is an illegal exaction because it is intended to solve a speculative circulation problem that does not yet exist, and is unrelated to the impact of this specific subdivision amendment. The city may not require the exaction as a condition of approval, nor deny the application based solely on the property owner’s refusal to adhere to this condition. Rather, the city must review the application by considering the enacted standards of its MPD ordinance and making an administrative decision supported by ordinance-based reasons and substantial evidence.

Evidence

The Ombudsman’s Office reviewed the following relevant documents and information prior to completing this Advisory Opinion:

- Request for Advisory Opinion submitted by Jerry Carroll, received on September 22, 2022.

- Letter from Vaughn R. Pickell, City Attorney for Spanish Fork, received on October 28, 2022.

- Email from Jerry Carroll dated October 31, 2022.

- Email from Vaughn R. Pickell dated November 3, 2022.

Background

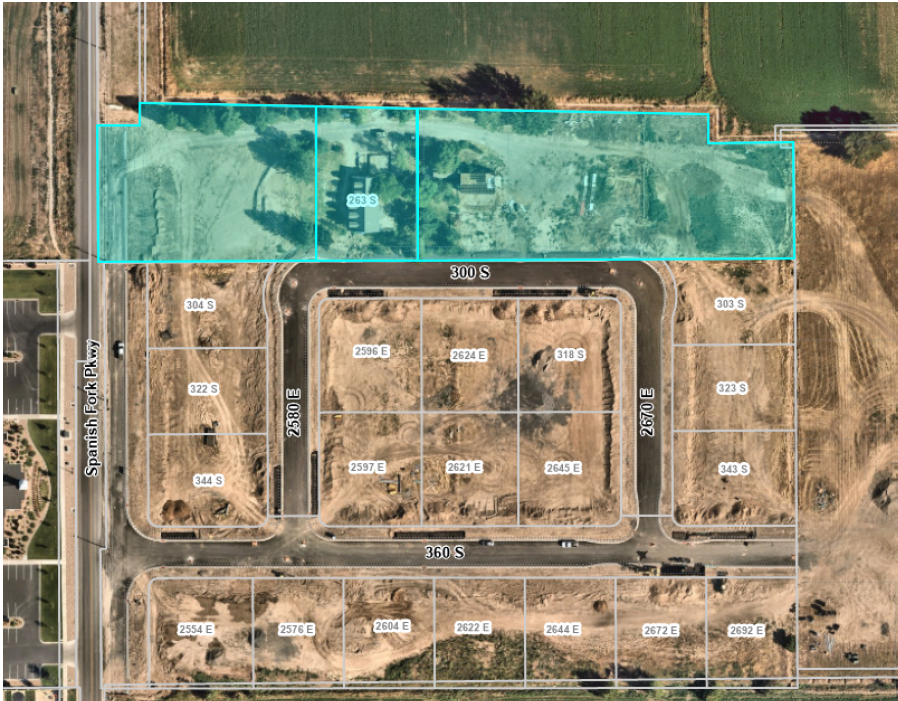

Jerry Carroll owns three adjoining parcels of property in Spanish Fork off of Spanish Fork Parkway, one of which features his existing home (see highlighted area below).

To the south of Mr. Carroll’s property is a recently recorded residential subdivision, the “Eagle Haven Subdivision, Plat A,” which was recorded in the office of the Utah County Recorder on April 21, 2022 (“Plat A”). Plat A was approved as a Master Planned Development (“MPD”), a type of planned unit development as an alternative to a standard subdivision that allows for approval of certain variation in setbacks, frontage widths, and other dimensional standards where the City Council makes particular findings. Spanish Fork Municipal Code (SFMC) § 15.3.24.030(A). The MPD-approved Plat A created 19 lots and provided three public streets which provide public access to the combined Carroll property by terminating at, or providing frontage to, the Carroll property—the north/south running streets of 2580 E and 2670 E that extend to the Carroll property border, and which each then “knuckle” toward the east/west running 300 S along the shared border with the Carroll property. The developer of Plat A also provided utilities that were stubbed at the Carroll property in anticipation of future development on the Carroll parcels.

Prior to recording Plat A, public access to the Carroll property had been provided by Spanish Fork Parkway only. Mr. Carroll approached the city about subdividing his parcels into several lots. However, due to the length and little frontage on Spanish Fork Parkway, his development option as a conventional subdivision would be limited to a 400-ft cul-de-sac from Spanish Fork Parkway. Instead, the City suggested that Mr. Carroll’s subdivision could be reviewed as an MPD by integrating with Plat A subdivision by plat amendment, which at the time only had preliminary plat approval.

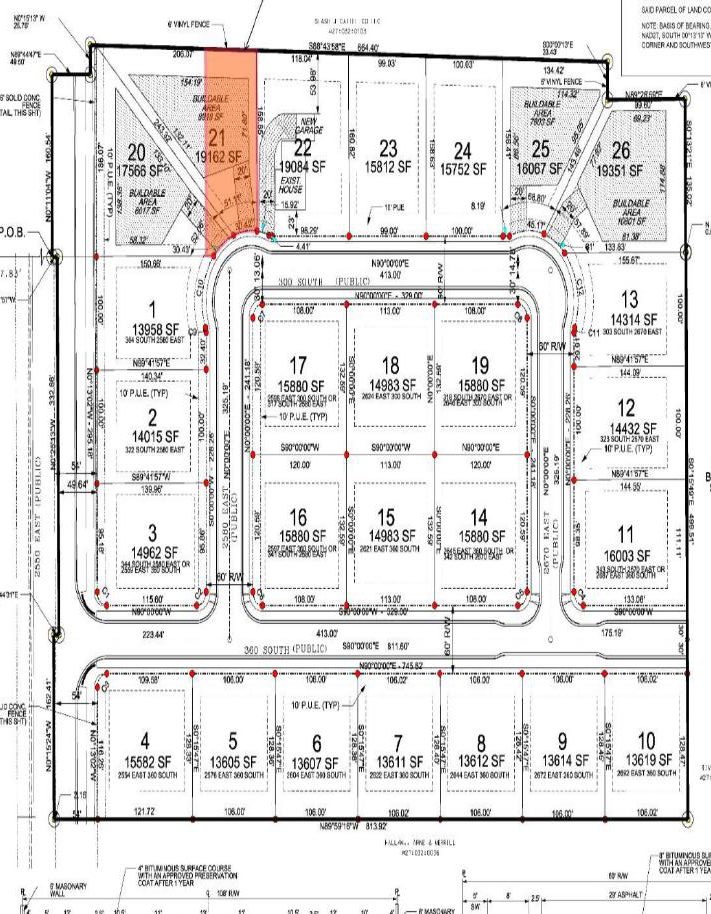

Mr. Carroll submitted an amended subdivision plat for the “Eagle Haven Subdivision” (“Amended Plat”) proposing the addition of seven lots fronting on 300 S, lots 20-26. Mr. Carroll’s existing home is situated on proposed lot 22. After submission to the City, Mr. Carroll received some redline comments back from planning staff, who concluded that Mr. Carroll’s proposal to add seven lots would result in the subdivision exceeding the maximum allowed density in the zone by one lot. Staff suggested eliminating one lot and providing a stub road across the Carroll property to undeveloped property to the north. Lot 23 was the lot suggested to be eliminated, putting the stub road adjacent to the proposed parcel with Mr. Carroll’s existing home.

Upon receiving this response from the City, Mr. Carroll filed a request for an Advisory Opinion with the Ombudsman’s Office on whether the City could lawfully require that he dedicate property and install improvements for a stub road across his property.

At a subsequent Development Review Committee (DRC) meeting, DRC members expressed concerns about the frontages of lots 20, 21, 25 and 26 as being too narrow. It was recommended that the proposed stub road not run through lot 23, as initially suggested by staff, but instead act as a northbound continuation of 2580 East, requiring the elimination of lot 21 and the reconfiguration of lot 20, but allowing for better frontage for lots 20 and 21, according to the DRC. See highlighted plat map, below.

No action on the application was taken by the DRC, however, because it was determined that more research may be needed on the widths of lots 20, 21, 25 and 26, and it was also discussed that Mr. Carroll had requested an Advisory Opinion from the Ombudsman’s Office on the issue of requiring the stub road. The DRC passed a motion to continue the proposal until an advisory opinion was issued or was withdrawn.

Analysis

The sole question for this Advisory Opinion is whether the City may require Mr. Carroll to install a stub road across his property as a condition of approval of his plat amendment application adding new lots to an MPD subdivision. An Advisory Opinion may be requested at any time before a final decision on a land use decision. See Utah Code § 13-43-205(1)(b). The application is still with the DRC, which has yet to make any formal recommendation to the City’s land use authority until this advisory opinion request is resolved.

While the question of whether a development exaction is lawful typically anticipates a certain proposal and conditions, as the analysis focuses on the very fact-specific inquiry of impact, we conclude here that regardless of its final location, requiring the installation of a stub road across the Carroll property to undeveloped land at the owner’s expense is an unlawful exaction as it is categorically unrelated the development impact of this application that proposes to add a limited number of lots to an improved street.

I. The Issue is Ripe for an Advisory Opinion

In responding to the Request for an Advisory Opinion, the City acknowledges that an Advisory Opinion serves as an opinion on an issue that is unripe for judicial review, and that State law allows a property owner to request an opinion at any point in the land use application process. Nevertheless, the City argues that this particular request is very premature and unripe as the recommending body has not even made a recommendation to the land use authority. The City argues that referring the issue to the Ombudsman does not serve the parties well before such decisions can be made, and that the request has had the effect of chilling the communication between the City and the developer, and as a result, the DRC has tabled the issue until the opinion is issued. The City states that it wants to move the process forward but is reluctant to do so at the risk of paying attorney fees should the opinion be issued contrary to the City’s understanding of the law. See, id. § 13-43-206(12) (court may award attorney fees under certain circumstances where a party knowingly violates the law after issuance of an advisory opinion).

The Advisory Opinion process is meant to serve as a dispute-resolution tool. An opinion is not binding on the parties, and unless requested by the local government, does not stay the progress of a land use application. Id. § 13-43-206(11)&(16). In other words, nothing is stopping the City from moving the application forward except its own reluctance, which we suspect may stem from an assumption that involvement by the Ombudsman’s Office is somehow adverse to the City’s interests. If so, we feel this assumption is very unfortunate. It fails to recognize the legislature’s purpose in creating the advisory opinion process, and fails to utilize the Ombudsman’s Office as the resource that it can be for land use applicants and local governments alike.

To be sure, we think this instance is the very kind of situation in which an advisory opinion may be most helpful. That is, where the local government has identified some condition or requirement it is considering imposing on a land use application, though no formal decision has been made, and where the applicant is opposed to the condition on grounds that it might not be lawful. Should the parties reach an impasse on the issue, obtaining the opinion of the Ombudsman as an appointed neutral serves to give the parties an independent answer they can then use to continue engaging with each other over the issue as the application moves forward to a final decision.

Even where the local government has not made a formal decision on an application, so long as there is sufficient information about the government’s disposition on a particular issue, the issue is ripe to provide an advisory opinion. Typically, as part of the advisory opinion process, the Ombudsman obtains this necessary information from the government entity by “seek[ing] a response . . . to the issues raised in the request for advisory opinion.” Id. § 13-43-206(8). In this case, the City’s response to the advisory opinion request provides enough information for our Office to opine on the proposed exaction.

II. Incentive Zoning Approvals Must Still Comply with Exaction Standards

A development exaction means a “contribution[] to a governmental entity imposed as a condition precedent to approving the developer’s project.” B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake County. (B.A.M. I), 2006 UT 2, ¶4. Development exactions may implicate the Takings Clause of the U.S. Constitution and Article I Section 22 of the Utah Constitution—which protect private property from governmental taking without just compensation. See, B.A.M. I, 2006 UT 2, at ¶34.

Utah’s Land Use Development and Management Act (LUDMA), as applied to municipalities, provides that a municipality may impose an exaction on development proposed in a land use application, if:

(a) an essential link exists between a legitimate governmental interest and each exaction; and

(b) each exaction is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.

Id. § 10-9a-508(1).

As noted by the Utah Supreme Court, this language in LUDMA is a verbatim codification of the “Nollan/Dolan” test extracted from the United States Supreme Court decisions of Nollan v. Cal. Coastal Comm’n, 483 U.S. 825 (1987), and Dolan v. City of Tigard, 512 U.S. 374, 114 S. Ct. 2309 (1994). If a development exaction satisfies the Nollan/Dolan test, as codified, it is a lawful exaction; if it does not, it is an unconstitutional taking requiring just compensation.

At issue is a condition that the City has expressed it will require before approving applicant’s proposed amendment to a Master Planned Development, which the City describes as “an optional subdivision type” that is “an alternative to a standard subdivision,” allowed “only if the City Council makes particular findings,” and for which approval “is not guaranteed.”

Such “optional” development standards are sometimes known as “incentive” or “bonus” zoning, which is a land use regulatory technique that allows a community to obtain various public amenities from a builder or developer without having to pay for them directly, normally allowing a developer to exceed certain regulation limits in return for providing one or more public amenities. 2 Zoning and Land Use Controls § 8.01 (2022).

Assuming such bargained-for development options are not required as the only option for developing land within the municipality, see, Utah Code 10-9a-532, these optional forms of development approvals make certain “discretionary benefits” available to developers above and beyond their development entitlements under conventional zoning regulations.

The City mounts an initial argument that requiring Mr. Carroll to provide a stub road as a condition of MPD approval would not be a development exaction because Mr. Carroll can alternatively develop his property without the condition as a conventional subdivision, but the flexibility the MPD ordinance provides makes evaluation of an MPD much like a negotiation, and requiring the stub road is simply consideration for the bargain.

However, the type of development approval chosen does not change whether or not a condition is considered a development exaction. As stated, any contribution to a governmental entity imposed as a condition precedent to approving the developer’s project is a development exaction, see, B.A.M. I, 2006 UT 2, at ¶4, and according to LUDMA’s plain language, must satisfy the codified Nollan/Dolan test in order to be imposed on development proposed in a land use application. Utah Code 10-9a-508(1).

Additionally, even in absence of LUDMA’s codification of the Nollan/Dolan test for all exactions, the United States Supreme Court decision of Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Mgmt. Dist. would also direct that even “discretionary benefits” afforded by incentive zoning schemes would not evade the limitations of Nollan and Dolan under the unconstitutional conditions doctrine, which stands for the principle that “the government may not deny a benefit to a person because [the person] exercises a constitutional right.” 570 U.S. 595, 604.[1]

With that in mind, bargained-for zoning or other forms of selected development options are not a free-for-all for a local government in the kind of things they can demand. The government does not evade the exaction requirements of Section 508 by giving the land use applicant a Hobson’s choice of either conceding to an unconstitutional condition or denial of the permit altogether—simply because they could still develop a “less ambitious” project under conventional development standards. See, Koontz. at 611. By enacting a regulatory scheme that makes elective development options available, the local government has held out certain governmental benefits that a landowner should be able to take advantage of without an expectation that they will need to forfeit their constitutional rights to do so.

Rather, it should be expected that where an incentive zoning scheme potentially allows a more intensive use of land due to permissible variations from applicable zoning restrictions, the resulting project may also have increased impact from that of a standard development. The question then, just as it is with conventional development, is whether an exaction imposed in a bargained-for zoning approval satisfies the codified Nollan/Dolan test found in Section 508. If it does not, it is illegal, and cannot be made either a condition of approval, or the sole reason for flat out denial in the case that it is not accepted by the landowner.

As discussed below, we conclude that the requirement in question for a stub road across applicant’s property is an illegal exaction because it lacks an essential link to a legitimate governmental interest and is unrelated in nature to the development’s impact. As such, the City may not withhold MPD approval solely based on the applicant’s refusal to agree to give up his constitutional right to compensation in deeding property for public use.

III. The Stub Road is an Illegal Exaction

The exaction standard found in Section 508 is a two-prong test. A municipality may impose an exaction on development proposed in a land use application, if:

(a) an essential link exists between a legitimate governmental interest and each exaction; and

(b) each exaction is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.

Utah Code § 10-9a-508(1).

The essential link, or “nexus” requirement is derived from the Nollan case, which involved the California Coastal Commission demanding a public easement across the Nollans’ beachfront lot in exchange for a permit to demolish an existing bungalow and replace it with a three-bedroom house. While the Supreme Court assumed that the Coastal Commission had articulated a legitimate state interest of diminishing “blockage of the view of the ocean” caused by building a bigger home, it nevertheless concluded, as later summarized in Dolan, that:

[T]he Coastal Commission's regulatory authority was set completely adrift from its constitutional moorings when it claimed that a nexus existed between visual access to the ocean and a permit condition requiring lateral public access along the Nollans' beachfront lot. How enhancing the public's ability to “traverse to and along the shorefront” served the same governmental purpose of “visual access to the ocean” from the roadway was beyond our ability to countenance. The absence of a nexus left the Coastal Commission in the position of simply trying to obtain an easement through gimmickry, which converted a valid regulation of land use into “an out-and-out plan of extortion.”

Dolan, 512 U.S. 374, 386-87 (internal citations omitted).

Following Nollan’s lead, Utah courts have assumed that a city’s traffic goals are a legitimate governmental interest for exaction purposes. See, B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake City., 2004 UT App 34 (citing to Smith Inv. Co. v. Sandy City, 958 P.2d 245, 255 (Utah Ct. App. 1998) (“It is clear that the flow of traffic is a legitimate concern of a municipal legislative body in its enactment of zoning regulations.”)); see also, Carrier v. Lindquist, 2001 UT 105, ¶ 18 (“In order for a government to be effective, it needs the power to establish or relocate public throughways . . . for the convenience and safety of the general public.”).

Here, however, similar to as in Nollan, while the City’s legitimate governmental interest of efficient traffic flow can be promoted by requiring streets to connect between developments generally, in this particular case, there exists no nexus between that interest and requiring this developer to install a short street extension that dead-ends to undeveloped land. Simply put, without any evidence that residential development is imminent for the vacant land, speculation about possible future development simply does not support a conclusion that the exacted dead-end street will actually accomplish the objective that the City has based the condition on.

Moreover, even were we to assume that such an exaction aimed at speculative future development could reasonably promote a legitimate governmental interest, it would nevertheless fail the second part of the exactions test—rough proportionality—as it is unrelated in nature to the immediate impact of this development.

When engaging in the rough proportionality analysis, as detailed in the Dolan case, it must be determined whether the nature of the exaction and impact are related. Utah courts have clarified this relationship by looking at the “exaction and impact in terms of a solution and a problem, respectively,” in that “the impact is the problem, or the burden that the community will bear because of the development. The exaction should address the problem. If it does, then the nature component has been satisfied.” B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake County, 2008 UT 45, ¶ 10 (“B.A.M. II”).

Here, the City mischaracterizes the problem it is intending to solve. The problem, as articulated by the City, is that if developments are not connected to each other by local roads, the City will be left with an “unmanageable street network, landlocked parcels, isolated neighborhoods, [and] traffic congestion.”

However, the City fails to tie that generality to the specific impact of Mr. Carroll’s proposed development. The extent of this subdivider’s impact is limited to only the proposed addition of up to seven lots to the existing MPD subdivision. Contrary to the City’s assertions, we simply do not agree that extending the subdivision’s streets across the Carroll property to undeveloped land will in any shape or form cure “unmanageable street network, landlocked parcels, isolated neighborhoods [or] traffic congestion” that is somehow the consequence of this development. The problems identified by the City are not caused by, or even measurably attributable to a contribution from, this development proposal apart from the separate impacts of the previously approved MPD subdivision or other future development that is yet to occur.

The government has other means to promote its legitimate transportation interests that are outside or beyond the immediate impact of a particular development to serve the larger community. For example, where a municipality may have identified a particular anticipated transportation corridor through private property that it wishes to preserve from being developed, Utah law allows certain powers for “corridor preservation.” See, Transportation Corridor Preservation, Utah Code Title 72, Chapter 5, Part 4. Ultimately, however, these powers will eventually require the government to compensate the landowner for acquiring its property for transportation purposes.[2]

What the government cannot do, however, is “require a property owner to dedicate private property for some future public use as a condition of obtaining a [development approval] when such future use is not occasioned by the construction sought to be permitted.” Dolan, 512 U.S. at 390 (quoting Simpson v. North Platte, 206 Neb. 240, 248, 292 N.W.2d 297, 302 (1980). Without the required nexus or proportionality, such a requirement is merely “an excuse for taking property simply because at that particular moment the landowner is asking the city for some license or permit.” Id. (quoting Simpson, at 245, 292 N.W.2d at 301).[3]

Because of this, the City cannot “force [Mr. Carroll] to dedicate and improve [the stub road] based solely on its own transportation planning goals, rather than the impacts of [Mr. Carroll’s] subdivision, because this would force [Mr. Carroll] alone to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole.” See, B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake County, 2004 UT App 34, ¶ 52 (Orme, J., dissenting) (quoting Armstrong v. United States, 364 U.S. 40, 49, 80 S. Ct. 1563, 1569, 4 L. Ed. 2d 1554 (1960)). “A strong public desire to improve the public condition will not warrant achieving the desire by a shorter cut than the constitutional way of paying for the change.” Dolan, 512 U.S. at 396 (quoting Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 U.S. 393, 416, 67 L. Ed. 322, 43 S. Ct. 158 (1922)).

Mr. Carroll has indicated that he is not opposed to the City compensating him to acquire the portion of his property it desires to accomplish its future transportation objectives. However, short of this, the City may not otherwise require Mr. Carroll to improve and dedicate his property for the dead-end stub road as a condition of his subdivision approval, as this is an illegal exaction amounting to an unconstitutional taking of private property for a public use without just compensation; nor may the City withhold approval solely based on Mr. Carroll’s refusal to adhere to the requirement as doing so denies Mr. Carroll of his constitutional right to just compensation.

IV. The City Must Review the Application by Applying the Standards of its MPD Ordinance as an Administrative Act

As discussed above, the City may not deny the MPD application based solely on the applicant’s refusal to adhere to an unconstitutional exaction. However, nor is it true that the City may simply otherwise deny the application for “any” reason. The City argues that as the application seeks approval as an MPD, an optional development type, Mr. Carroll is not entitled to approval. Specifically, the Spanish Fork Municipal Code provides that MPD applicants “are not entitled by right to have a project approved as a Master Planned Development,” and that the City Council “has sole discretion to approve a Master Planned Development or not.” SFMC § 15.3.24.030.H.

However, because this code section providing for the MPD approval process was enacted by land use regulation, despite the ordinance’s language to the contrary, an applicant should, and must, be entitled to approval “if the application conforms to the requirements of applicable land use regulations . . . and development standards.” Utah Code § 10-9a-509(1)(a)(ii). Any decision on an application made pursuant to the MPD ordinance—even if made by the City Council who otherwise acts as the legislative body of the City—is an administrative act made by the City Council in the role of the land use authority. Utah Code § 10-9a-306(3) (a land use decision of a land use authority is an administrative act, even if the land use authority is the legislative body).[4]

While the municipality’s legislative body holds the municipality’s policy making powers, the function of the land use authority is to make decisions to “carry out legislative policies and purposes [as] acts of administration.” Salt Lake County Cottonwood Sanitary Dist. v. Sandy City, 879 P.2d 1379, 1382 (Utah Ct. App. 1994). Administrative acts are “limited to the evaluation of specific criteria fixed by law,” See, Krejci v. Saratoga Springs, 2013 UT 74, ¶ 34.

This means that the City Code’s language, as written, suggesting that the City Council has “sole discretion to approve . . . or not,” is a legal fiction.[5] As recently noted by our Utah Supreme Court, “the [land use authority] does not have absolute power, even with [a] broad grant of discretion.” N. Monticello All., LLC v. San Juan Cty., 2022 UT 10, ¶ 35 n.12. In all instances, where issuing an administrative land use decision, a land use authority is “bound by the terms and standards of applicable land use regulations,” Utah Code § 10-9a-509(2), and must “apply the plain language of [those] regulations.” Utah Code § 10-9a-306.

In other words, while the City’s Code may have attempted to illegally delegate complete discretion to the City Council as a land use authority to approve or denying a Master Planned Development for any reason, the City Council must nevertheless reach a decision that intentionally considers the applicable MPD provisions in light of the ordinance’s stated legislative policies and purposes, and upon making appropriate, required findings that are supported by substantial evidence.[6] Again, by enacting an administrative approval process for an MPD, the City has held out certain development benefits that should be achievable by complying with the standards the City has spelled out in the ordinance. The MPD ordinance articulates those requirements and conditions that should produce development in line with the goals articulated in the MPD ordinance. Therefore, if the proposed development meets the objective, ordinance-based requirements of the MPD Code, it would be difficult to conceive of a scenario in which the stated goals of the MPD ordinances have not, by definition, been met.

Conclusion

Requiring Mr. Carroll to improve and dedicate a stub road across his property to dead-end in undeveloped land in order to serve speculative future development is an illegal exaction because it lacks a nexus to the City’s stated connectively and traffic concerns, and is unrelated to the impact of Mr. Carroll’s development. The City may therefore not impose the requirement as a condition of approval, or deny the application solely on Mr. Carroll’s refusal to adhere to the condition, even if MPD approval is sought as an alternative to conventional development entitlements. Instead, the City must review the MPD application according to the City Code’s stated requirements and standards and make a decision supported by affirmative findings and substantial evidence.

Jordan S. Cullimore, Lead Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

NOTE:

This is an advisory opinion as defined in Section 13-43-205 of the Utah Code. It does not constitute legal advice, and is not to be construed as reflecting the opinions or policy of the State of Utah or the Department of Commerce. The opinions expressed are arrived at based on a summary review of the factual situation involved in this specific matter, and may or may not reflect the opinion that might be expressed in another matter where the facts and circumstances are different or where the relevant law may have changed.

While the author is an attorney and has prepared this opinion in light of his understanding of the relevant law, he does not represent anyone involved in this matter. Anyone with an interest in these issues who must protect that interest should seek the advice of his or her own legal counsel and not rely on this document as a definitive statement of how to protect or advance his interest.

An advisory opinion issued by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman is not binding on any party to a dispute involving land use law. If the same issue that is the subject of an advisory opinion is listed as a cause of action in litigation, and that cause of action is litigated on the same facts and circumstances and is resolved consistent with the advisory opinion, the substantially prevailing party on that cause of action may collect reasonable attorney fees and court costs pertaining to the development of that cause of action from the date of the delivery of the advisory opinion to the date of the court’s resolution. Additionally, a civil penalty may also be available if the court finds that the opposing party—if either a land use applicant or a government entity—knowingly and intentionally violated the law governing that cause of action.

Evidence of a review by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman and the opinions, writings, findings, and determinations of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman are not admissible as evidence in a judicial action, except in small claims court, a judicial review of arbitration, or in determining costs and legal fees as explained above.

The Advisory Opinion process is an alternative dispute resolution process. Advisory Opinions are intended to assist parties to resolve disputes and avoid litigation. All of the statutory procedures in place for Advisory Opinions, as well as the internal policies of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman, are designed to maximize the opportunity to resolve disputes in a friendly and mutually beneficial manner. The Advisory Opinion attorney fees and civil penalty provisions, found in Section 13-43-206 of the Utah Code, are also designed to encourage dispute resolution. By statute they are awarded in very narrow circumstances, and even if those circumstances are met, the judge maintains discretion regarding whether to award them.

[1] Koontz held that the Nollan/Dolan line of cases involves a special application of this doctrine that “protects the Fifth Amendment right to just compensation for property the government takes when owners apply for land-use permits.” 570 U.S. 595, 604. Namely, the Nollan/Dolan decisions reflect two realities in the land-use permitting process. First, “applicants are especially vulnerable to the type of coercion that the unconstitutional conditions doctrine prohibits because the government often has broad discretion to deny a permit that is worth far more than property it would like to take. . . . So long as the [permit] is more valuable than any just compensation the owner could hope to receive for the [exacted property], the owner is likely to accede to the government’s demand, no matter how unreasonable. Extortionate demands of this sort frustrate the Fifth Amendment right to just compensation, and the unconstitutional conditions doctrine prohibits them.” Id. at 605. The second reality of the permitting process is that “many proposed land uses threaten to impose costs on the public that dedications of property can offset,” and that “[i]nsisting that landowners internalize the negative externalities of their conduct is a hallmark of responsible land-use policy, and we have long sustained such regulations against constitutional attack.” Id. Therefore, “Nollan and Dolan accommodate both realities by allowing the government to condition approval of a permit on the dedication of property to the public so long as there is a ‘nexus’ and ‘rough proportionality’ between the property that the government demands and the social costs of the applicant’s proposal.” Id. at 605-06.

[2] The transportation corridor preservation powers under Utah’s Rights-of-Way Act not only include the ability to acquire fee simple title or even an easement to private property by voluntary purchase due to future corridor needs, but also the power to limit development by land use regulation and official maps. Utah Code § 72-5-403. But in the case of development limitations by regulation, the affected landowner may petition the government to acquire fee simple or a lesser interest. Id. § 72-5-405(3). If the government petitioned is not prepared to pay for such an acquisition at the option of the property owner, then it can no longer limit or restrict the affected property’s development. Id.

[3] As noted by Utah’s Court of Appeals, Nebraska’s Simpson opinion cited by the U.S. Supreme Court in Dolan articulated the “reasonable relationship” test for exactions found in the majority of states, which the Supreme Court concluded was “close[] to the federal constitutional norm,” and in all other respects besides name only, was adopted by the Supreme Court and renamed the “rough proportionality” test.

B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake County, 2004 UT App 34 n.11.

[4] See also, Utah Code § 10-9a-103 (defining the terms “land use application”, “land use authority”, “land use decision”, “land use regulation”, and “legislative body”).

[5] The applicable standard of review for a land use decision—even those made upon an exercise of delegated discretion—is that the decision is “presume[d] . . . valid unless the land use decision is “arbitrary and capricious” for failure to be “supported by substantial evidence in the record.” Utah Code § 10-9a-801(3). Truly, the notion of “sole discretion to approve … or not” is the very definition of arbitrary and capricious. Black’s Law Dictionary 125, 254 (defining “arbitrary” as “depending on individual discretion,” and “caprice” as “contrary to the evidence or established rules of law”).

[6] See, supra, note 5.