Advisory Opinion 249

Parties: Auburn Hills, LLC and Hyrum City

Issued: January 11, 2022

Topic Categories:

Exactions on Development

If a phase of development is applied for and approved independent of prior subdivision applications, and absent any explicit agreement otherwise, the relevant impact to be offset by exaction is the immediate proposal presented in the land use application, without regard to previously approved phases, including past contributions and improvements. Likewise, potential future development activity in the surrounding area bears no relation to the impact of the immediate development applied for.

Hyrum City’s requirements for certain road dedications is an illegal exaction where the City simply requires the dedications pursuant to its development standards without basing the imposition on an individualized determination of impact. Moreover, where the purpose for the City’s exactions appear to primarily be to serve future development needs according to desired city planning, the developer is being required to pay for impacts beyond its own and to bear burdens which should be borne by the public at large, in violation of the developer’s constitutional rights.

DISCLAIMER

The Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman makes every effort to ensure that the legal analysis of each Advisory Opinion is based on a correct application of statutes and cases in existence when the Opinion was prepared. Over time, however, the analysis of an Advisory Opinion may be altered because of statutory changes or new interpretations issued by appellate courts. Readers should be advised that Advisory Opinions provide general guidance and information on legal protections afforded to private property, but an Opinion should not be considered legal advice. Specific questions should be directed to an attorney to be analyzed according to current laws.

Advisory Opinion

Advisory Opinion Requested by:

Local Government Entity:

Applicant for Land Use Approval:

Type of Property:

Opinion Authored By:

Richard B. Plehn, Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

Issue

Do certain road dedications amount to illegal exactions as imposed on a new application for a phase of a residential subdivision?

Summary of Advisory Opinion

Ordinances imposing development exactions go beyond the mere regulation of property as they mandate contribution of private property for the public’s use. Exactions amount to an illegal taking if they require the developer to offset more than just the impact of its proposed development.

In imposing an exaction, even if by applying the plain language of generally applicable ordinances, the government must first make some sort of individualized determination that the required contribution is related both in nature and extent to the impact of the proposed development. The relevant impact to be offset by condition is limited in scope to what is proposed in the land use application under review. If a phase of development is applied for and approved independent of prior subdivision applications, and absent any explicit agreement otherwise, the relevant impact to be offset by exaction is the immediate proposal presented in the land use application, without regard to previously approved phases, including past contributions and improvements. Likewise, potential future development activity in the surrounding area bears no relation to the impact of the immediate development applied for.

Hyrum City’s requirements for certain road dedications is an illegal exaction where the City simply requires the dedications pursuant to its development standards without basing the imposition on an individualized determination of impact. Moreover, where the purpose for the City’s exactions appear to primarily be to serve future development needs according to desired city planning, the developer is being required to pay for impacts beyond its own and to bear burdens which should be borne by the public at large, in violation of the developer’s constitutional rights.

Review

A Request for an Advisory Opinion may be filed at any time prior to the rendering of a final decision by a local land use appeal authority under the provisions of Utah Code § 13-43-205. An Advisory Opinion is meant to provide an early review, before any duty to exhaust administrative remedies, of significant land use questions so that those involved in a land use application or other specific land use disputes can have an independent review of an issue. It is hoped that such a review can help the parties avoid litigation, resolve differences in a fair and neutral forum, and understand the relevant law. The decision is not binding, but, as explained at the end of this opinion, may have some effect on the long-term cost of resolving such issues in the courts.

A Request for an Advisory Opinion was received from Dan Larsen, on behalf of Auburn Hills LLC, on April 27, 2021. A copy of that request was sent via certified mail to Mayor Stephanie Miller, 83 West Main Street, Hyrum Utah, 84319 on May 6, 2021.

Evidence

The Ombudsman’s Office reviewed the following relevant documents and information prior to completing this Advisory Opinion:

- Request for Advisory Opinion submitted by Dan Larsen on behalf of Auburn Hills LLC, received on April 27, 2021.

- Hyrum City’s statement in response to the Request for Advisory Opinion, received May 12, 2021.

- Property Owner’s Response to City’s statement, received May 28, 2021.

- City’s reply statement, received July 2, 2021.

- Various Hyrum City documents and meeting minutes, as cited in the opinion.

Background

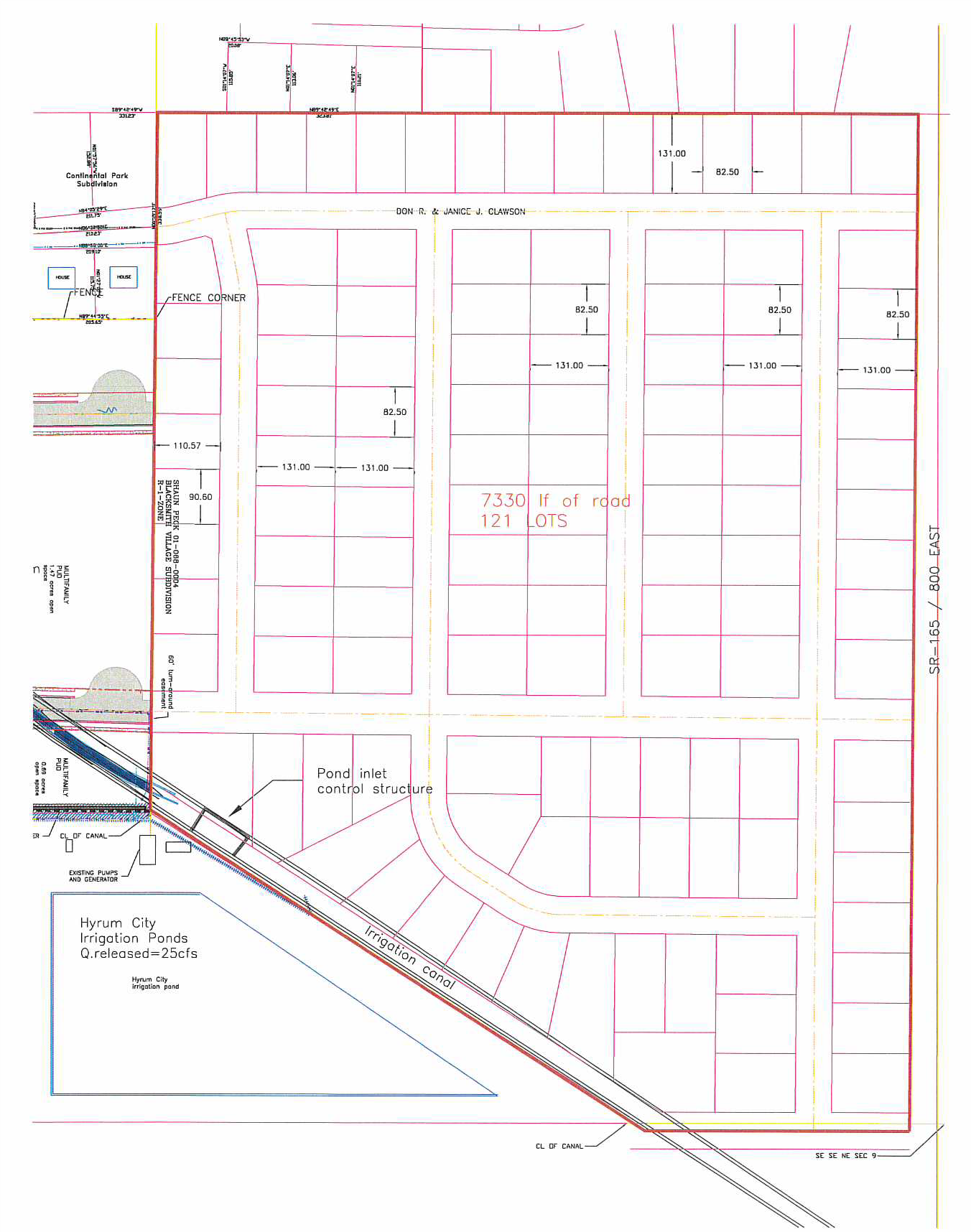

In August of 2016, Hyrum City (“City”) approved a concept plan for the Auburn Hills Subdivision, a proposed multi-phase development creating 121 single family building lots on the approximately 44-acre parcel at “600 South 800 E.” (see illustration on following page)

During the concept stage, it was discussed[1] that Auburn Hills would connect with another multi-phase subdivision to the east via the proposed 600 S. The concept also proposed to dedicate and improve a half-width of a 68-foot collector road along the southern end of the property along approximate 700 South, as the developer had met with UDOT about a potential access at this point.

Following concept plan approval of the Auburn Hills subdivision, the applicant returned for preliminary plat approval. The staff summary noted, however, that in departure of the approved concept plan, the applicant was “not asking for preliminary plat approval for the whole property at this time” due to the expected build-out time, and had “excluded about 14 acres from what is in the Concept Plan.”[2]

The applicant instead sought preliminary plat approval of an 86-lot subdivision over six phases to develop 30 acres of the 44-acre parcel, while excluding a 14-acre remainder at the southern end of the property, beyond 600 South. The staff summary concluded that this revised proposal “should still work as a stand-alone development as proposed in the preliminary plat,” though continuing to note that 700 South, which was previously discussed but would now be excluded as part of the omitted remainder, “will be needed as a connector road for future growth to the south.”[3]

Upon review, despite the revised proposal’s omission of the southern portion of the property, the Planning Commission continued to comment on 700 South, that it would need to be available, the Commission noted, to carry traffic for future growth in that area.[4]

The City granted preliminary plat approval for phases 1-6 the Auburn Hills Subdivision, and over the last several years, phases 1 through 6 have been built out after obtaining final plat approval for each phase in accordance with the 2016 preliminary plat approval.[5]

Auburn Hills LLC (“the Owner”) is the owner of the remainder parcel from the previously approved Auburn Hills Subdivision, Phases 1-6. In February of 2021, the Owner presented a preliminary plat proposal for “Auburn Hills - Phase 7,” which proposed 41 single family building lots on the 14-acre remainder parcel between approximately 650 East to 800 East and 600 South to 700 South.”[6]

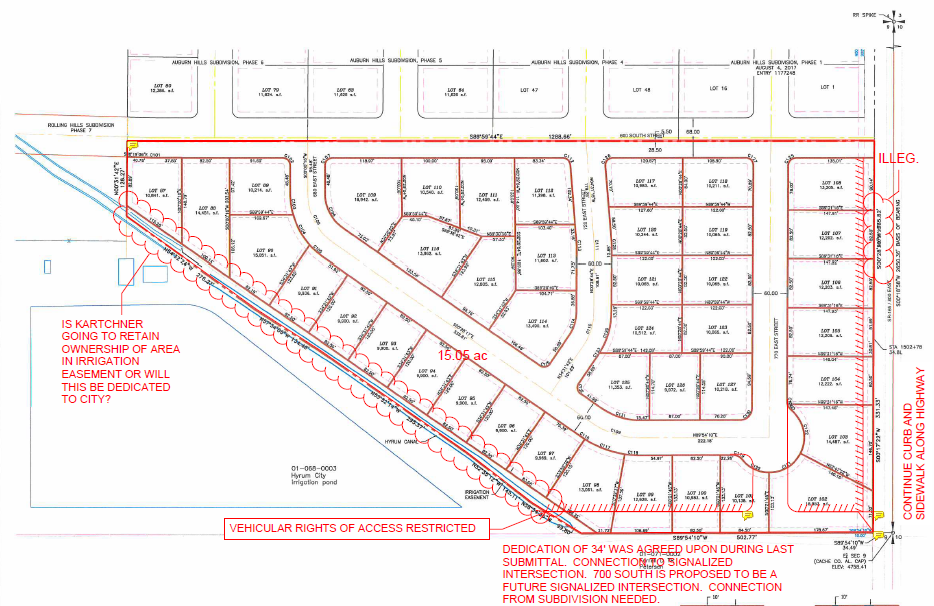

Regarding roads, this preliminary plat proposal for Phase 7 differed in several aspects from what had initially been proposed in the original Auburn Hills concept plan when the remainder was part of the larger parcel. Principally, the half-width dedication for 700 South was no longer depicted. Similarly, the continuation of 770 E from the prior subdivision, which had been proposed at concept plan as a north/south connection between 600 S and 700 S, no longer extended the full length of the property, instead veering west and connecting to two other local access streets. Finally, Phase 7 proposed no additional dedication for right-of-way along Highway 165.

City staff returned redline comments (see illustration on following page) depicting three additional road dedications more in line with the originally approved concept, as described below. When the proposed preliminary plat came before the City Council, there was significant discussion and debate on each of the road dedications, and the Council tabled the matter and suggested that the Owner request an advisory opinion as to whether the dedications could be required.

Half-width for minor collector (700 South)

The Property for Phase 7 is bordered on the north by 600 S, the 68-foot minor collector[7] that was dedicated and improved during prior phases of the Auburn Hills development entirely at the Owner’s cost. Along the south border of the Property, the City has similarly asked for a dedication of 34 feet for a half-width of proposed 700 South, also to be a minor collector. 700 S would be a continuation of existing 6200 South terminating at the eastern border of the property. The City anticipates that 700 South will be a future signaled intersection on SR-165.

Deceleration lane for State Route 165 (Hyrum City – 800 East)

Bordering the property to the east, State Route 165 is an existing two-lane paved highway that is state-owned and maintained. The City, however, maintains the park strip (curb, gutter, sidewalk), and has asked for a dedication for additional right-of-way to be used for a park strip, as well as to allow for a slip/deceleration lane for right turns on proposed 700 South. North of the Phase 7 property, a similar slip/deceleration lane was required for the entire length of the prior Auburn Hills subdivision phases along SR-165, with the applicant also providing the majority of the costs of the improvements for the park strip.

Full width, stub road, (770 East)

As proposed, Phase 7 includes a north/south running road as a continuation of 770 E from the previous Auburn Hills subdivision, but which veers west before the end of the property to connect to other interior streets within Phase 7. The City has, instead, asked for a dedication of additional property that would allow 770 E to continue all the way to the southern border of the property, permitting future connection with the proposed 700 S.

For each of these rights-of-way, the City asks for a dedication only, and has not asked the Owner to contribute to any street improvements, noting that the City does not foresee that maintaining these portions of road will be cost-effective. Auburn Hills asserts that none of the road dedications are necessary because of the development’s impact, and are being required without compensation. Auburn Hills has requested an Advisory Opinion to determine whether the required road dedications amount to illegal exactions.

...

Analysis

I. Exacted Road Dedications Are One Method the Government Meets Public Needs

Building public roads to service residential development is one of the quintessential services provided by government. The government has different tools at its disposal to ensure that adequate amounts of land—which may start in private hands—be converted to public roadways that effectively service the community.

For example, where the need for a road is not immediate, the government may purchase private property on a voluntary basis to be used to preserve transportation corridors up to 30 years in advance of using those rights to actually construct transportation facilities.[8] Alternatively, if immediately necessary for public use, and if a willing seller is not found, the government may resort to its power of eminent domain to condemn private property if just compensation is paid.[9] When the government is the instigator of these road initiatives, it bears the cost of the acquisition and improvements, paid by the public at large.[10]

Another method of acquiring and financing road infrastructure is through the imposition of a development exaction. An exaction is defined as “a government-mandated contribution of property imposed as a condition” of development approval.[11] The term “exaction” may include any condition on development, including the payment of money, installation of specific improvements, donation of property, and/or providing public improvements.[12] The government’s goal in imposing a development exaction is to displace, as much as possible, the burden and cost to the public for things like transportation infrastructure onto developers by asking each developer to pay its “equitable share”[13] for roads necessitated by new development. This presumes that new development activity creates additional impact on the surrounding community that can be appropriately offset by specific exactions.

Here, the City has required three road dedications as a condition of subdivision approval for the Phase 7 development application. This requirement is a development exaction, and must therefore be imposed pursuant to state and constitutional law.

I. Legislated Exactions Must Comply with State and Constitutional Law, As Applied

The Hyrum City Code contains development standards that impose certain exactions for roads, as follows:

16.20.060 Public Improvements - Adjacent Streets

It shall become the responsibility of the developer to complete all of the necessary public improvements to one-half of all streets adjacent to the proposed development. This shall be done at the subdivider's sole expense.

16.20.170 Street Improvements

A. …

B. The arrangement of streets in new subdivisions shall make provision for the continuation of the existing streets in adjoining areas and shall provide access to un-subdivided adjoining areas insofar as such continuation or access shall be deemed necessary by the Planning Commission and approved by the City Council.

C. New streets must connect with existing public streets.

D. The subdivider shall install curbs, gutters, and sidewalks on existing and proposed urban streets adjacent to and in all subdivisions, including on the rear of such lots that back on major streets not permitted access to such streets and those proposed for swales meeting City design standards.

In the present case, all of the exactions imposed by the City on Phase 7 of the Auburn Hills development are as a result of the City applying select requirements derived from the above development standards.

The City asserts that all property is subject to reasonable control and regulation by government entities to protect and promote the health, safety, and welfare of the public, and argues that the exactions imposed by the City on Phase 7 of Auburn Hill’s development are valid and legal because they are required by city code.

However, land use regulations are also subject to the takings clause protections of both federal and state constitutions stating that private property may not be taken for public use without just compensation.[14] Land use ordinances that impose a development exaction are therefore treated differently because they go beyond the mere regulation or restriction of private property to require the actual forfeiture of private property to the public.

The United States Supreme Court has addressed when a development exaction amounts to an illegal taking of private property for public use in the cases of Nollan v. Cal. Coastal Comm’n,[15] and Dolan v. City of Tigard.[16] The resulting analysis from these two cases is known as the “rough proportionality” test, which was directly codified in Utah’s Land Use Development and Management Act (“LUDMA”), at Section 10-9a-508, as follows:

A municipality may impose an exaction or exactions on development proposed in a land use application . . ., if:

(a) an essential link exists between a legitimate governmental interest and each exaction; and,

(b) each exaction is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.[17]

If a proposed exaction satisfies the rough proportionality test, described in Section 508, it is valid. If the exaction fails the test, it violates protections guaranteed by the Takings Clauses of the U.S. and Utah Constitutions and is illegal.[18]

It is therefore not enough to simply look to whether a particular exaction is required by an application of a city’s development code, and to look no further. An otherwise facially valid ordinance that mandates a particular exaction may nevertheless be illegal as applied to a particular development application.[19] The appropriate question, then, is whether an exaction—even expressly permitted by city ordinances—is otherwise compliant with Section 508, and ultimately the constitution, as imposed.

II. Threshold Determination of the Proposed Development

One aspect of the dispute between the parties is how the exactions imposed for Phase 7 should be considered in light of the developer’s prior phases and approvals, with both parties looking to the prior phases and past contributions and improvements to support their positions of whether the current exactions imposed on Phase 7 are valid.

Section 508 is framed in terms of exactions on “development proposed in a land use application.” The appropriate impact that needs to be determined by the local government, therefore, is determined by the scope of the land use application under review.

If phased development is applied for under Hyrum City ordinances, the landowner seeking approval for a phased development obtains concept plan and preliminary plat approval for the entire subdivision depicting each phase, and then proceeds with final plat approval of the individual phases.[20] City ordinances provide that the concept plan is “an informal discussion document” and its approval is “used as a guide for preparing a Preliminary Plat,” and that ultimately the preliminary plat may “alter the Concept Plan based on changed circumstances, hearing input,” or otherwise.[21]

Applied to phased development, this suggests that whether to approve a development project as independent subdivisions or as a cohesive phased development should be discussed at the concept plan stage, and that, accordingly, if the applicant proceeds with preliminary plat approval for multiple phases, impacts should be determined overall, and applicable exactions should be identified and imposed at the preliminary plat stage.

Here, while the initial concept plan approved for the Auburn Hills subdivision anticipated 121 single family building lots on the entirety of the approximately 44-acre parcel, the subsequently approved preliminary plat was limited to Phases 1 through 6, while expressly omitting a remainder portion of the larger parcel for future development. As directed by the City’s ordinances, the City properly granted preliminary plat approval of Phases 1 through 6 together, and the developer carried out each phase by obtaining final plat approval for the respective phases as appropriate.

Now, while labeled “Auburn Hills, Phase 7” by the developer, this new application for Phase 7 is not really a sequential phase of previously approved Auburn Hills Subdivision in the legal sense. Rather, it is a standalone subdivision that began with its own preliminary plat approval independent from the prior plat of Phases 1 through 6.

As its own land use application, Phase 7 is not an opportunity, for either party, to revisit the development exactions for the previously approved subdivision that were negotiated, agreed to, and approved by the local land use authority, that are no longer are appealable. Had it been the intention of the parties that Phase 7 be considered overall with the previously approved subdivision, it should have either been included in the preliminary plat approval of the entire subdivision, or else been specifically preserved for overall consideration through some form of development agreement; but it was not.

Because Phase 7 is the only development included in the land use application under review, any exactions imposed must stand on their own merits by looking only to the impact of Phase 7.

III. Required showings under the exactions test

In asking for the three right-of-way dedications as conditions of approving the Phase 7 development, the City has provided a number of different reasons to justify why the roads are necessary or why it has required the dedications. These reasons include, among others, that (1) they are required by ordinance, (2) they were discussed during the initial concept plan, (3) they are consistent with prior improvements and the general layout of city blocks, (4) they are needed for future growth, or (5) it will be costlier to acquire the right-of-way in the future.

Based on these reasons, the City has concluded that what it has asked for is “reasonable.” However, the applicable legal standard for exactions is not a “reasonableness” standard in light of city needs not related to the development’s direct impacts; rather, the appropriate standard is the rough proportionality test, which simply allows a municipality to impose an exaction if (a) there exists an essential link between a legitimate governmental interest and each exaction, and (b) each exaction is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.

As to the essential link, or “nexus” requirement, the parties spend little to no time on this part of the test in their respective submissions.[22] Utah courts have recognized that because it is “clear that the flow of traffic is a legitimate concern of a municipal legislative body in its enactment of zoning regulations,”[23] the mandatory dedication of land for roads is considered a common type of development exaction.[24] There does not appear to be any dispute here that an essential link exists between the legitimate governmental interest of ensuring roads for residential development and the exaction on new development to require dedication of property for such roads. The essential link element, at least, is therefore satisfied in this case.

That said, once the essential link is established, the only remaining consideration for whether the road dedications can be constitutionally required is the relationship between the exaction and development impact. While all of the reasons provided by the City may be good reasons why the rights-of-way are needed by the City for its own planning purposes, none of them relate to the development’s impact. The amount a city may exact from a developer depends upon the particular development’s impacts, not a subdivision ordinance, prior expectations, or the city’s need or desire for certain improvements. The City may plan for and intend that certain roads be established, but it may only require the Owner to contribute to these roads if the requirement to do so is roughly equivalent to the impact created by the proposed development activity.

A. The Road Exactions were Not Imposed as a Result of a Determination of Impact

The “rough proportionality” test imposes a burden on the government to “make some sort of individualized determination that the required dedication is related both in nature and extent to the impact of the proposed development.”[25] While “[n]o precise mathematical calculation is required,” local governments “must make some effort to quantify [their] findings” that a dedication will directly offset the impacts of development.[26]

Here, it is clear that the City’s purposes and basis for imposing these road exactions on the Phase 7 development are for a number of reasons unrelated to the impact of Phase 7, specifically. Being based on considerations other than the development’s impact, Hyrum City’s road dedications fail because they are not based on any individualized determination that the exactions are roughly proportionate to the development’s specific impact.[27]

We might infer from the City’s arguments that the impact of Phase 7 would be some increase in traffic and contributing, generally, to congestion and connectivity issues. Even then, in order for the government to meet its burden to determine the relationship between a road dedication exaction and the development’s impact, something “beyond [a] conclusory statement that [the exaction] could offset some of the traffic demand generated” is required.[28]

The one example of the “rough proportionality” test we have from Utah courts is found over a series of appellate decisions in the case of B.A.M. Development v. Salt Lake County, which similarly involved disagreement as to whether the imposition of a road dedication on a residential subdivision was an excessive exaction. Specifically, Salt Lake County conditioned the approval of a 15-acre residential subdivision on a dedication of land for the future widening of 3500 South, a major road abutting the development.

To determine whether the nature of the exaction and impact are related, Utah courts have adopted the method of looking at the exaction and impact in terms of a solution and problem, respectively. The impact is the problem, or the burden that the community will bear because of the development.[29] If “the solution (the exaction) directly addresses the specific problem (the impact),” the nature component is satisfied.[30] The City’s solution is not required to be exclusive to only the development; the fact that the greater community might also benefit from the solution is not an absolute disqualifier.[31] However, the government must nevertheless “show that its proposed solution to the identified public problem is ‘roughly proportional’ to that part of the problem that is created or exacerbated by the landowner’s development.”[32]

According to the Utah Supreme Court, for the extent portion of the analysis, specifically, this implies that both the exaction and the impact should be measured in the same manner, or using the same standard; the most appropriate measure being cost.[33] Therefore, the extent analysis is distilled into comparing the respective costs to the parties—that is, it must be determined what the cost of dealing with the impact would be to the City, absent any exaction, and what the cost of the exaction would be to the developer, and whether the two costs are roughly proportionate, or “equivalent.”[34] To accomplish this, Utah courts have noted that “[t]he impact of the development can be measured as the cost to the municipality of assuaging the impact. Likewise, the exaction can be measured as the value of the land to be dedicated by the developer at the time of the exaction, along with any other costs required by the exaction.”[35]

After several remands, the B.A.M. court instructed the trial court to compare the market value of the exacted property with the cost to the government of alleviating the development’s projected increase in traffic volume, comparing dollars to dollars. In that case, this was ultimately possible because the court record was replete with quantifiable findings made by the county in reviewing the subdivision proposal, including the subdivision’s impact in terms of increased traffic trips, the cost to the government in undertaking road improvements to address the increased traffic in the area, as well as the value of the land exacted and other costs of the exaction on the developer (such as lost lots).

Similar to the B.A.M. dispute, this case likewise involves a road dedication requirement imposed on a residential subdivision, and as was the case in B.A.M., it could likewise be assumed here that the impact of a residential development is an increase in traffic. However, unlike the B.A.M. case, there has been no determination of the portion of increased traffic that can be directly attributed to the proposed development, nor of the cost to the City of assuaging the development’s specific impact, or the cost to the developer for the exaction. Without these findings, it cannot be established that the exaction is roughly proportionate—or roughly equivalent—in nature and extent, to the development’s impact.

B. The City’s Road Dedications Amount to More than a Typical Road Exaction

While the Utah Supreme Court believes that applying the rough proportionality test should be “a relatively straightforward task,”[36] in reality, we have noted that in many cases, it is difficult for a local government to provide the cost analysis necessary for the full extent aspect of the rough proportionality analysis as anticipated in the B.A.M. opinions.[37]

The City, in fact, argues that its required dedications, and 700 South in particular, are “consistent with development plans in many other municipalities to dedicate the half-width of regular roads.”

We acknowledge that requiring dedication and improvements for a “half-width” of road, curb, gutter, and sidewalk for the frontage of property is a common practice, and our Office has found that this practice, as a yardstick or “rule-of-thumb,” is a generally accepted baseline as to compliance with the rough proportionality test—in that, if every property abutting the road were to each dedicate and improve a half-width along their respective frontage, the entire road would be covered by public contributions in proportion to each abutting property’s respective impact, measured by frontage.

However, we have noted that this baseline half-width exaction often fails to account for individual circumstances, and therefore may need to be adjusted in any given case in light of evidence that the specific development’s impact does not represent a typical impact. This is generally true where more than a half-width for frontage is required, or the road in question is a collector or arterial, as opposed to local, street, where the development’s impact may represent a smaller share of traffic generated or used by the road. In such instances, there must certainly be some effort on the government’s part to quantify findings to parse out the impact of the proposed development from the rest of the impact of the greater community, when the issue is determining who will ultimately pay for roads that also service the community at large.[38]

In this case, while we have no information on impact or the actual respective costs to either party, we know that the City’s apparent solution to this problem is more than a common exaction of a half-width of frontage. Rather, the City has imposed road dedications on three rights-of-way: a half-width for an abutting minor collector (700 S), the continuation of an interior local road to connect the subdivision to the collector (770 E), and the widening of the major arterial road (SR 165) that would be serviced by the collector.

There does not appear to be any argument that these additional dedications are otherwise necessary in order for the proposed lots to meet applicable ordinance-based criteria, such as development access for egress/ingress, fire or other public safety, etc., and as such, consisting of collectors and arterial roads, as opposed to strictly local roads, it is clear that the roads, considered together, primarily benefit the greater community. This is supported by the City’s several statements that the roads in question are needed to accommodate future growth in the area.

So while assuming Phase 7 will amount to a some share of impact on these community roads, this is an instance where the impact of this development must be parsed out from the rest of the impact of the greater community by specific, quantified findings, in order to determine the appropriate share of costs for roads that serve as collectors, which the City’s own ordinances consider as “carr[ying] traffic from all areas to the major street system,”[39] or arterial roads.

Because the City has not determined Phase 7’s individual impact, apart from general community impacts or the City’s own planning needs, the road exactions are illegally imposed as they are not shown to be roughly proportionate, in nature and extent, to the specific impact of Phase 7.

Conclusion

The City’s legitimate planning needs may not be accomplished by unconstitutional means. Land use ordinances that require private property be dedicated to a public use must be applied so as not to violate the property owner’s constitutional rights as a taking without just compensation. A developer may lawfully be asked to dedicate property or make contributions to public improvements in order to offset the immediate impact of its proposed development activity. The developer may not, however, be burdened with the current or future needs of the community at large by offsetting more than its impact. Because the exactions imposed by the City have not been demonstrated to be related in nature and extent to offset the developer’s specific impact, the City’s imposition of these exactions is an unlawful exaction.

...

Jordan S. Cullimore, Lead Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

...

NOTE:

This is an advisory opinion as defined in § 13-43-205 of the Utah Code. It does not constitute legal advice, and is not to be construed as reflecting the opinions or policy of the State of Utah or the Department of Commerce. The opinions expressed are arrived at based on a summary review of the factual situation involved in this specific matter, and may or may not reflect the opinion that might be expressed in another matter where the facts and circumstances are different or where the relevant law may have changed.

While the author is an attorney and has prepared this opinion in light of his understanding of the relevant law, he does not represent anyone involved in this matter. Anyone with an interest in these issues who must protect that interest should seek the advice of his or her own legal counsel and not rely on this document as a definitive statement of how to protect or advance his interest.

An advisory opinion issued by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman is not binding on any party to a dispute involving land use law. If the same issue that is the subject of an advisory opinion is listed as a cause of action in litigation, and that cause of action is litigated on the same facts and circumstances and is resolved consistent with the advisory opinion, the substantially prevailing party on that cause of action may collect reasonable attorney fees and court costs pertaining to the development of that cause of action from the date of the delivery of the advisory opinion to the date of the court’s resolution.

Evidence of a review by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman and the opinions, writings, findings, and determinations of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman are not admissible as evidence in a judicial action, except in small claims court, a judicial review of arbitration, or in determining costs and legal fees as explained above.

The Advisory Opinion process is an alternative dispute resolution process. Advisory Opinions are intended to assist parties to resolve disputes and avoid litigation. All of the statutory procedures in place for Advisory Opinions, as well as the internal policies of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman, are designed to maximize the opportunity to resolve disputes in a friendly and mutually beneficial manner. The Advisory Opinion attorney fees provisions, found in § 13-43-206, are also designed to encourage dispute resolution. By statute they are awarded in very narrow circumstances, and even if those circumstances are met, the judge maintains discretion regarding whether to award them.

Endnotes:

________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Hyrum City, Planning Commission Meeting Minutes, August 11, 2016.

[2] Preliminary Plat Auburn Hills Subdivision ~600 South 800 East, Planning Commission Meeting September 8, 2016.

[3] Preliminary Plat Auburn Hills Subdivision ~600 South 800 East, Planning Commission Meeting September 8, 2016.

[4] Minutes of the Hyrum City Planning Commission, September 8, 2016.

[5] Phase 1 created 16 lots and received final plat approval in 2017. Phases 2 and 3 were approved together in 2018, creating 11 lots and 12 lots, respectively. Phase 4 was approved in 2019, and Phase 5 in April of 2020, each adding 16 lots. Finally, Phase 6 added 15 lots and was approved in September of 2020.

[6] Minutes of the Hyrum City Planning Commission, February 11, 2021.

[7] As noted above, while the City’s Transportation Master Plan identified this stretch of 600 South as a planned secondary arterial route, which according to the City’s ordinances should be a width of 99 feet, the road appears to have instead been approved and installed as 68-foot minor collector. See Hyrum City, Resolution 15-06 (March 19, 2015). The City’s submission clarifies these widths as “local,” “minor collector,” and “arterial roads,” respectively.

[8] See Transportation Corridor Preservation, Part 4 of Utah’s Rights-of-Way Act (“ROW Act”), Utah Code § 72-5-401 et seq. The Owner makes some limited argument that the City’s actions do not comply with the Transportation Corridor Preservation powers under the ROW Act. In short, the ROW Act allows local governments to preserve transportation corridors by limiting development through local ordinances and official map. The Owner appears to argue that because some of the rights-of-way the City is exacting aren’t reflected in the City’s master transportation plan, they are demanded in violation of the ROW Act. We note, simply, that because the ROW Act allows development to be limited for transportation corridor preservation by land use regulation, the City’s imposing a development exaction on a subdivision development pursuant to its ordinances, generally, is consistent with the city’s transportation corridor preservation powers under the ROW Act. The real question to be determined, therefore, is simply whether the exactions imposed for corridor preservation purposes are valid as complying with the rough proportionality test, and are not excessive amounting to a taking and requiring compensation. This is the issue discussed in this opinion.

[9] See generally, Utah Code § 78B-6-504.

[10] Either by using general taxes or other funding mechanisms; otherwise, the government might collect impact fees on new development or enact a special assessment that attempts to localize costs to those who directly benefit from the road improvements.

[11] B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake County, (BAM III), 2012 UT 26, ¶16.

[12] Koontz v. St. Johns River Water, 133 S. Ct. 2586 (2013).

[13] See B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake County, 2004 UT App 34, ¶16, (quoting Banberry Development Corporation v. South Jordan City, 631 P.2d 899, 903 (Utah 1981) (analyzing a related issue of the appropriateness of municipal service fees, which are a type of exaction)).

[14] U.S. Const. amend. V. This promise binds the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. Chicago, Burlington & Quincy R.R. Co. v. Chicago, 166 U.S. 226, 234, 17 S. Ct. 581, 41 L. Ed. 979 (1897). The Utah Constitution reinforces the protection of private property against uncompensated governmental takings in article I, section 22.

[15] 483 U.S. 825, 107 S. Ct. 3141, 97 L. Ed. 2d 677 (1987).

[16] 512 U.S. 374, 114 S. Ct. 2309, 129 L. Ed. 2d 304 (1994).

[17] Utah Code § 10-9a-508(1) (emphasis added).

[18] Call v. West Jordan, 614 P.2d 1257, 1259 (Utah 1980).

[19] The City appears to acknowledge this concept by its actions, in that whereas a plain application of city ordinance might require a developer not only to dedicate property along adjacent roads but also to install improvements, the City has only asked the Owner for certain road dedications without requiring any improvements or a fee in lieu thereof. Because local governments otherwise must apply the plain language of land use ordinances, see Utah Code § 10-9a-306, and have no discretion to deviate from the mandatory provisions thereof, Utah Code § 10-9a-509(2), the City’s foregoing the full application of its development standards in imposing an exaction on the developer appears to acknowledge that doing so might result in an excessive, and therefore illegal, burden on the developer.

[20] HCC § 16.20.015.

[21] HCC § 16.10.030.

[22] The City appears to confuse the essential link requirement with rough proportionality, noting that “[a]n example of lack of proportionality is having a land owner dedicate and build a road when they want to build a shed.” This is, rather, a great example of the lack of nexus, in that the legitimate government interest (regulating construction of structures, including sheds) bears no essential link or nexus with the exaction imposed by the government (building a new road) to obtain approval. Other than this, the City notes that while the City Code would require the full-width infrastructure buildout of the roads along SR 165 and 700 South, the City acknowledges that there is no nexus upon this development to build these roads at this time, which is why the City has only required the dedication for these additional roads, which the City argues has nexus and proportionality. This speaks more to rough proportionality, however, which will be discussed in the next section.

[23] Smith Inv. Co. v. Sandy City, 958 P.2d 245, 255 (Utah Ct. App. 1998) (quoting Kenneth H. Young, Anderson's American Law of Zoning § 3A.04 (4th ed. 1996)).

[24] See BAM III, 2012 UT 26 at ¶ 16.

[25] Dolan, 512 U.S. 374, at 391.

[26] BAM III, 2012 UT 26 at ¶ 19 (citing Dolan, 512 U.S. 374 at 395-96).

[27] We do not mean to say that the exactions fail simply because the City has not made express findings. In fact, the Utah Supreme Court appears to have left open the question as to just what “degree of specificity” the rough-proportionality test requires. See Id., 2012 UT 26 at ¶ 35.

[28] Dolan, 512 U.S. 374, at 395 (emphasis added).

[29] BAM II, 2008 UT 74 at ¶10 (emphasis added).

[30] Id., ¶¶ 10, 13 (emphases added).

[31] In reviewing differing state approaches to exactions, one common standard that was squarely rejected by the United States Supreme Court was what it termed as the “specific and uniquely attributable” test. Under this test, if the local government cannot demonstrate that its exaction is directly proportional to the specifically created need, the exaction is a veiled exercise of eminent domain to confiscate private property behind the defense of police regulations. Dolan 512 U.S. 374, at 389-90.

[32] BAM II, 2008 UT 74 at ¶ 10 n.3, (quoting Burton v. Clark County, 91 Wn. App. 505, 958 P.2d 343, 354 (Wash. Ct. App. 1998)).

[33] Id., at ¶ 11.

[34] Id., at ¶13. Noting that the phrasing of the “rough proportionality” test has “engendered vast confusion about just what the municipalities and courts are expected to evaluate when extracting action or value from a land owner trying to improve real property,” the Utah Supreme Court attempted to clarify the standard by instead referring to the question as whether the exaction and impact are roughly “equivalent.” Id., at ¶8.

[35] Id., at ¶11.

[36] Id., at ¶13.

[37] While it may often be an involved process for local governments to make the quantified findings necessary for a cost-to-cost comparison for each exaction case, it is nevertheless necessary where the impacts of several contributors must be portioned, and should not be an unexpected exercise. Because development exactions implicate takings concerns, we feel it appropriate to draw parallels between exactions and the processes required for an exercise of eminent domain, as an explicit invocation of the power to take private property for the public use. Namely, before private property can be taken, the government bears an initial burden to determine that “the use to which it is to be applied is a use authorized by law,” and that the taking “is necessary for the use.” Utah Code § 78B-6-504(1). Furthermore, before taking occupancy of a property, the condemning entity must provide “proof . . . of []the value of the premises sought to be condemned,” Utah Code § 78B-6-510(2)(a), recognizing that the property owner is “entitled to an explanation” of how the property’s value “was calculated.” See Utah Code § 78B-6-505(2)(b)(ii). Therefore, because an exaction demands the forfeiture of private property for the public’s use, the government is expected to make quantifiable findings to provide an explanation of why the condition being imposed is related, both in nature and extent, to the proposed development’s impact and will not otherwise require any compensation to be paid for the government’s acceptance of the contribution.

[38] This is often the heavy work performed by impact fees and the required analyses and findings that accompany their enactment and imposition. See generally, Utah’s Impact Fees Act, Utah Code § 11-36a-101 et seq.

[39] See HCC § 16.04.0100 “Collector street,” “Major streets.”