Advisory Opinion 243

Parties: ARB Investments, LLC / West Jordan City

Issued: September 2, 2021

Topic Categories:

Exactions on Development

In response to the developer’s requested rezone for a proposed residential development, the city has asked a developer to dedicate an off-site portion of property for a future roadway as a condition precedent to favorable legislative approval, and also stated that administrative approval of the development would likewise require the road dedication pursuant to city ordinances. The rough proportionality standard applies to all exactions, regardless of source, whether proposed during legislative rezone proceedings, or imposed as a condition of approval pursuant to enacted land use regulations. While the City has yet to make an individualized determination that the required dedication satisfies the rough proportionality standard, the information available suggests that the rough proportionality standard cannot be met by the proposed exaction because dedication and construction of a dead-end road intended for a future overpass to serve future development does not appear to be related in nature to the immediate impact of the developer’s project.

DISCLAIMER

The Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman makes every effort to ensure that the legal analysis of each Advisory Opinion is based on a correct application of statutes and cases in existence when the Opinion was prepared. Over time, however, the analysis of an Advisory Opinion may be altered because of statutory changes or new interpretations issued by appellate courts. Readers should be advised that Advisory Opinions provide general guidance and information on legal protections afforded to private property, but an Opinion should not be considered legal advice. Specific questions should be directed to an attorney to be analyzed according to current laws.

Advisory Opinion

Advisory Opinion Requested by:

ARB Investments, LLC

Local Government Entity:

West Jordan City

Applicant for Land Use Approval:

ARB Investments, LLC

Type of Property:

Agricultural

September 2, 2021

Opinion Authored By:

Richard B. Plehn, Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

Issues

Does the city’s requirement that a developer dedicate a portion of property lying outside of the area planned for development for a future road as a condition of project approval amount to an illegal exaction?

Summary

All exactions, whether proposed as a response to a request for favorable legislative action, or administratively imposed as conditions on approval, must bear an essential link to a legitimate governmental interest, and be roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.

In response to the developer’s requested rezone for a proposed residential development, the city has asked a developer to dedicate an off-site portion of property for a future roadway as a condition precedent to favorable legislative approval, and also stated that administrative approval of the development would likewise require the road dedication pursuant to city ordinances. The rough proportionality standard applies to all exactions, regardless of source, whether proposed ad hoc during legislative amendment proceedings, or imposed as a condition of approval as a result of enacted land use regulations. While the City has yet to make an individualized determination that the required dedication satisfies the rough proportionality standard, the information available suggests that the rough proportionality standard cannot be met by the proposed exaction because dedication and construction of a dead-end road intended for a future overpass to serve future development does not appear to be related in nature to the immediate impact of the developer’s project.

Review

A Request for an Advisory Opinion may be filed at any time prior to the rendering of a final decision by a local land use appeal authority under the provisions of Title 13, Chapter 43, Section 205 of the Utah Code. An advisory opinion is meant to provide an early review, before any duty to exhaust administrative remedies, of significant land use questions so that those involved in a land use application or other specific land use disputes can have an independent review of an issue. It is hoped that this can help the parties avoid litigation, resolve differences in a fair and neutral forum, and understand the relevant law. The decision is not binding, but, as explained at the end of this opinion, may have some effect on the long-term cost of resolving such issues in the courts.

A Request for an Advisory Opinion was received from Justin Matkin, Attorney for ARB Investments, LLC on March 4, 2021. A copy of that request was sent via certified mail to Jamie Brooks, Interim City Clerk for West Jordan City, 8000 South Redwood Road, 3rd Floor, West Jordan Utah 84088, on March 5, 2021.

Evidence

The Ombudsman’s Office reviewed the following relevant documents and information prior to completing this Advisory Opinion:

- Request for an Advisory Opinion, submitted by Justin P. Matkin, Attorney for ARB Investments, LLC (“ARB”), received on March 4, 2021.

- Response to Request for Advisory Opinion, submitted by Duncan T. Murray, Assistant City Attorney, City of West Jordan, received on April 6, 2021.

- Reply to Response to Request for Advisory Opinion, submitted by Justin Matkin, received on April 9, 2021.

- (Final) Response to Reply Regarding Request for Advisory Opinion, submitted by Duncan Murray, received April 27, 2021.

- Email reply from Justin Matkin RE: Final Response Letter for City of West Jordan v. ARB Investments (Request for Advisory Opinion), received May 5, 2021.

Background

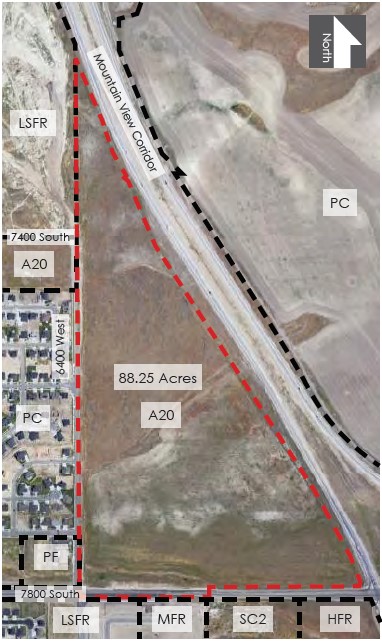

ARB Investments, LLC (“ARB”) owns an approximately 86.14-acre parcel of land in West Jordan, zoned A-20 (Agriculture). The parcel is triangular in shape, its southern border formed by 7800 South, its western border formed by 6400 West, and its hypotenuse running alongside Mountain View Corridor. West of the parcel, an existing dirt road, 7400 South, dead ends at the parcel’s western border, near the upper part of the triangular parcel. (An illustration of the existing parcel and the 7400 South terminus at its border can be found at this end of this section, as Figure 1)

The City of West Jordan has identified 7400 South on its Transportation Master Plan as a future essential transportation corridor, and a November 14, 2016 agreement with the Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) considers extending 7400 South across the ARB parcel and serving as a grade-separated crossing over Mountain View Corridor.[1]

On March 16, 2020, ARB submitted to the City of West Jordan a proposed Master Development Plan for a residential planned community development called the “Community at Bowman’s Arrow.” Under the submitted Master Development Plan, the parcel would be rezoned to IOZ, or, “Interchange Overlay Zone”—an optional overlay zone that may only be applied to defined areas impacted by Mountain View Corridor[2]—and would create approximately 2,000 new residential units. In the March 16, 2020 Master Development Plan, ARB acknowledged a continuation of 7400 South over its property, and contained the entirety of the proposed residential development to the south of the anticipated right-of-way, while leaving the northern tip of the triangular parcel as dedicated open space on the other side of the right-of-way—though proposing some improvements ancillary to the residential development, including some parking and a recreational trail, which would ultimately be city-owned facilities. (An illustration of the March 16, 2020 proposed development, including the anticipated extension of 7400 South across the parcel, can be found at this end of this section, as Figure 2)

However, in response to some feedback that the City may not be interested in accepting the dedication of open space north of the anticipated 7400 South extension,[3] ARB submitted a new Master Development Plan, dated June 23, 2020, which completely removed the proposed dedicated open space at the northern end of the parcel, as well as the portion for the anticipated continuation of 7400 South, proposing instead only the residential development on the remaining portion of the parcel south of the otherwise anticipated 7400 South. (An illustration of the revised June 23, 2020 proposal, reflecting removal of the 7400 South extension and any proposed development activity on the parcel above that point, can be found at this end of this section, as Figure 3)

In response to the new June 23, 2020 Master Plan, planning staff returned some red-line edits, including comments that the northern tip of the parcel could not be excluded from the proposal, particularly because “it contains master planned improvements” (because the June 23, 2020 plans no longer include any improvements in that northern portion, it is unclear whether this comment is assuming the improvements from the prior, March 16, 2020, version of the proposal). Moreover, staff commented that “7400 South Street must be included in the plan. This collector road will become a key traffic distributor to other arterial streets (5600 West and U-111[4]) in the future phases of the project.”

ARB takes these redline comments to mean that the City is conditioning approval of the Master Development Plan on ARB’s dedication of land across the undeveloped portion to be used for 7400 South as a development exaction, and alleges that the City’s basis for this exaction is its cooperation agreement with UDOT concerning the conditions required before Mountain View Corridor may move to Phase 2, including wherein UDOT agrees to construct a crossing at 7400 South so long as the City preserves and provides the necessary right-of-way.

ARB’s Master Development Plan, which includes the request for the necessary rezone, is still being reviewed by City staff and has not yet been forwarded to the City’s Planning Commission or City Council. ARB has submitted a Request for an Advisory Opinion asking this office to determine whether the City’s stated condition on ARB’s proposed development is a lawful exaction.

Figure 1 (existing plan)

Figure 2 (initial ARB plan)

Figure 3 (revised ARB plan)

Analysis

As is the case with many planned developments, ARB’s development proposal is a combination of requests, both for legislative action (i.e., rezone from A20 to the IOZ overlay to allow for residential uses) as well as subsequent—albeit concurrently proposed—administrative approval of a mixed-density residential development according to the desired rezone. In a nutshell, ARB views its proposal as a single application, and alleges that the City’s stated requirement that ARB dedicate property for the future 7400 South exchange as a required condition on its approval is therefore an exaction on development proposed in a land use application under Utah Code Section 10-9a-508.

The City, on the other hand, views ARB’s application piecemeal, constituting first and foremost a request for legislative action to rezone the subject property as a threshold for subsequent administrative review, and that the City’s stated conditions at this legislative stage do not even reach the issue of exactions under Section 10-9a-508, but are imposed consistent with the City’s sole legislative discretion to approve a rezone of the subject property for development purposes. The City further alleges, based on this position, that ARB’s request does not present any issue within the jurisdiction of the Property Rights Ombudsman to address in an Advisory Opinion. We disagree with the City’s assessment of this Office’s jurisdiction, as explained below.

I. Ombudsman Jurisdiction

Utah courts have defined development exactions to mean “contributions to a governmental entity imposed as a condition precedent to approving the developer’s project.”[5]

Utah’s Land Use Development and Management Act (“LUDMA”) provides, in Section 10-9a-508, that “[a] municipality may impose an exaction or exactions on development proposed in a land use application . . . if: (a) an essential link exists between a legitimate governmental interest and each exaction; and (b) each exaction is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.” The Utah Supreme Court has noted that the language in Section 10-9a-508 is a verbatim codification of the “rough proportionality test” extracted from the United States Supreme Court decisions of Nollan v. Cal. Coastal Comm’n[6] and Dolan v. City of Tigard.[7]

The Property Rights Ombudsman Act provides that an advisory opinion may be requested to determine compliance with Section 10-9a-508 “at any time before[] a final decision on a land use application by a local appeal authority.”[8]

Pertinent to both sections of the Utah code above is the term “land use application,” which LUDMA has defined as “an application that is: (i) required by a municipality; and (ii) submitted by a land use applicant to obtain a land use decision,” but which, however, does not mean “an application to enact, amend, or repeal a land use regulation.”[9]

As mentioned, ARB’s “application” submitted to the City involves both a request to rezone property, as well as a residential subdivision proposal consistent with the desired rezone. While the application’s rezone request asks the City to “enact [or] amend . . . a land use regulation” by asking for the City, by ordinance, to apply a different zoning designation to the ARB property,[10] the application also otherwise constitutes a request to “obtain a land use decision” as “required by [the] municipality”[11] for the proposed residential subdivision.

What’s more, while the City characterizes the imposition of its stated condition as being solely within its legislative discretion to approve the rezone request, the City further argues in its submissions that West Jordan City Code would require the dedication and construction of 7400 South regardless.[12] In other words, even if the application were to be reviewed by the City administratively, the City would require the dedication as a development exaction anyway.

So, while the portion of ARB’s application seeking administrative approval is contingent upon the desired rezone being approved legislatively, the portion of the application seeking the administrative approval is nevertheless a “land use application,” and the City has imposed, as “a condition precedent to approv[al],”[13] this requirement on “development proposed in a land use application.”[14]

We do not share the City’s concern that the issue is not ripe for advisory opinion review because the administrative portions of the application are dependent on the legislative approvals, which have yet to occur. The application, constituting both a request for legislative action and administrative review, has been submitted. The City will therefore be required to take final action on the administrative portions at some point. A request for an Advisory Opinion may be made “at any time” before the final decision of a local appeal authority.

We have traditionally viewed our jurisdiction to include questions of compliance even before a land use decision has been formally made, so long as there is sufficient information on how the City intends to apply its land use code to a given application. Here, as a land use application has at least been submitted, the proposed land use for which a land use decision is sought is already known, and, what’s more, the City has already suggested that applicable land use regulations would require an exaction in this case, in that 7400 South is in the City’s Transportation Master Plan, and the City’s ordinances require streets to be dedicated and constructed in compliance with the Transportation Master Plan.[15] There is no reason why the current request is “not ripe,”[16] therefore, for review of the proposed exaction’s compliance with Section 10-9a-508.

Accordingly, the City’s imposition of this condition in response to ARB’s land use application triggers our jurisdiction for review under Utah Code Sections 10-9a-508 and 13-43-205, respectively.

II. A Comment on “Proposed” Exactions in the Legislative Process

Development exactions implicate the Takings Clause of the U.S. Constitution and Article I Section 22 of the Utah Constitution, which protect private property from governmental taking without just compensation.[17]

As discussed above, because ARB’s application does include a request for a land use decision, our Office may provide an Opinion under Section 10-9a-508 about whether the City’s land use ordinances can require dedication and improvement of 7400 South as a condition precedent to approving the developer’s project. But what’s more, our Office additionally has a statutory duty “to identify state or local government actions that have potential takings implications and, if appropriate, advise those state or local government entities about those implications.”[18] In this spirit, and because development exactions implicate takings concerns, we offer some comments on the City’s characterization of the City Council’s ability to make certain demands at the rezoning stage of the development approval process.

While ARB’s requests for land use action by the City may have been submitted as one application, the City is right to view the included requests for legislative action and administrative land use approval as separate, sequential steps. After all, denial of the rezone request in the City’s legislative discretion makes approval of the proposed development a foregone conclusion. No one is arguing that the development proposed by ARB is entitled to approval under the zoning designation currently applied to the property.[19]

The City’s submissions suggest, however, that the City may not view any conditions proposed during the legislative rezone process to be development exactions at all, but merely a reflection of “what the City Council, in its sole legislative discretion, appears to be willing or not willing to do in the future regarding amending its land use regulation,” and that the City Council may “exercise its sole legislative discretion to require the dedication and construction of the portion of 7400 South.” Further, the City has asked “that the Ombudsman’s Office find that no illegal exaction exists under the present circumstances,” because the City “reserves the right, on behalf of the City Council, in its sole legislative discretion, to deny the . . . zone change application.”

First, we note that the constitution prohibits the governmental taking of private property without paying for it “no matter which branch is the instrument of the taking;”—The “[takings clause] is concerned simply with the act, and not with the governmental actor. There is no textual justification for saying that the existence or the scope of a State’s power to expropriate private property without just compensation varies according to the branch of government effecting the expropriation.”[20]

Second, we note that while aspiring developers do not have a right to future favorable zoning,[21] they do have a right to receive just compensation for the taking of private property, and a person may not be denied even a discretionary government benefit for exercising a constitutional right.[22] Therefore, the “rough proportionality” test is equally applicable where the government’s demands for property are phrased as conditions precedent to permit approval, as opposed to conditions subsequent to approval.[23]

All this to say that conditions proposed during a request for legislative action that require a contribution of property are still considered development exactions, and must pass the rough proportionality standard. The City Council may have the legislative discretion to deny a rezone request for a number of reasons; however, the applicant’s refusal to adhere to an unconstitutional condition may not be one of them.

III. Regulatory Exactions

The City’s suggestion that ARB’s rezone request must include dedication of 7400 South in order to be considered favorably by the City’s legislative body is not the focus of this opinion. Rather, consistent with our jurisdiction to determine compliance with Utah Code Section 10-9a-508,[24] the issue to be addressed by this opinion is whether the City may apply the City Code to ARB’s proposal to require dedication and construction of 7400 South.

As mentioned, in response to ARB’s revised Master Development Plan that excluded any anticipated continuation of 7400 South across ARB’s property, city staff returned some red-line comments that dedication and construction of 7400 South must be included in the proposal. In rebuttal to ARB’s allegation that the basis for this demand was an agreement with UDOT, the City has responded that “the primary reason for the City Council wanting to keep 7400 South Street as a part of the development proposal is because 7400 South Street is in the City’s Transportation Master Plan.”

West Jordan City Code provides that, “[a]s a condition of subdivision approval, the owner/subdivider shall install street extensions and widening as recommended by the city transportation master plan.”[25] Further, the code requires that “[s]treets along a proposed subdivision boundary shall be constructed to city standards and according to the city master transportation plan.”[26] For these reasons, the City argues, because “7400 South Street is in the Transportation Master Plan and is along the ‘subdivision boundary’ of the proposed Bowman’s Arrow development, the City Code requires the dedication and construction of 7400 South Street.”

Section 10-9a-508 provides as follows:

“A municipality may impose an exaction or exactions on development proposed in a land use application . . . if:

(a) an essential link exists between a legitimate governmental interest and each exaction; and

(b) each exaction is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.”

The Utah Supreme Court has noted that Utah’s legislature “intended to apply the rough proportionality test to all exactions, irrespective of their source,” whether resulting from an administrative review or a legislated regulatory scheme.[27]

One aspect of the rough proportionality test, as detailed in Dolan, is that the burden of proof in demonstrating whether an exaction satisfies the standard is placed on the government, which “must make some sort of individualized determination that the required dedication is related both in nature and extent to the impact of the proposed development.”[28] It is therefore not enough to impose an exaction because local ordinances require it, without further analysis. Even ordinances enacted by a municipality’s delegation of the State’s police power, while facially valid,[29] may be unconstitutional as applied to a particular development if the result is to require a public contribution from the developer that “amounts to . . . more than their equitable share,”[30] pursuant to the rough proportionality standard.

The City has clarified that “[n]o decisions have been made yet by City staff, the Planning Commission, or the City Council regarding the Current Applications,” and proffers that “[i]f the City Council, in its sole legislative discretion, in the future, approves the zone change application, the City will comply with Utah Code § 10-9a-508, the statute governing development exactions, with regards to the rezoned property.” In the meantime, the City notes that it is working to collect information necessary to determine the design for 7400 South Street. “Once the street is designed,” the City concludes, “a determination could be made as to the proportionate share of the costs the City, ARB Investments, and other applicable owners would be required to make pursuant to an analysis based upon Utah Code § 10-9a-508.”

IV. The Proposed Exaction Does Not Appear to be Roughly Proportionate in Nature

While we have stated that our Office’s jurisdiction for advisory opinions extends to before a land use decision has been made, it is also true that the utility of our opinion is limited to the information available at any given stage in the development process. However, where a written advisory opinion has been requested consistent with our jurisdiction, we are obliged to provide it.[31]

To this point, the City has only informed ARB that, if the rezoning of ARB’s parcel is approved, ARB’s request for development approval under the City’s IOZ zoning ordinances will be subject to dedication and construction of 7400 South across ARB’s property, though no design has been determined, with no certain share of the cost yet attributable to ARB.

We can confidently opine, at least, that any requirement that ARB dedicate property or contribute to construction of public improvements in 7400 South as a condition of its development approval, even as a result of application of West Jordan’s City Code, is a development exaction that must meet the requirements of Section 10-9a-508. This includes something more than merely identifying that applying the plain language of applicable land use regulations would require some form of contribution. Rather, it is the City’s burden to make an individualized determination that the resulting required dedication is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.

While we do not have all the details of what the City will ultimately require, we know that the City intends to require extension of a public right-of-way at 7400 South across the ARB parcel, and that this extension will connect to a future overpass over Mountain View Corridor when the corridor moves to Phase 2 development. In other words, the City may not yet have made a determination of what ARB’s impact will be, but they have at least identified, more or less, what kind of contribution will be required. There is enough information from the parties’ arguments, then, to conclude that the City’s exaction may not satisfy at least one aspect of the rough proportionality standard. An exaction must satisfy all the elements of the rough proportionality standard to be valid. If the exaction fails any part of the test, it is unconstitutional.[32]

One of the required elements of the rough proportionality test is that an exaction must be “roughly proportionate . . . in nature . . . to the proposed development,”[33] for which reason the government must “must make some sort of individualized determination that the required dedication is related . . . in nature . . . to the impact of the proposed development.” In analyzing whether the nature of the exaction and the impact are related, Utah Courts have directed that parties should look at the exaction and impact in terms of a solution and a problem, respectively. “[T]he impact is the problem, or the burden that the community will bear because of the development. The exaction should address the problem. If it does, then the nature component has been satisfied.”[34]

ARB argues that the City’s anticipated exaction would not solve any problem created by the development, simply because the exaction “seeks a dedication of land to construct a road from nowhere to nowhere.” Since the 7400 South extension appears to be anticipated as a future overpass for Mountain View Corridor, but because Mountain View Corridor is still in Phase 1 with no definite time frame for moving to Phase 2, ARB argues that the City’s exaction appears to be more of an opportunity to make progress on the City’s own system-wide transportation plans, as opposed to being concerned with any projected impact of ARB’s development.

On the other hand, the development proposes to add up to 2,000 residential units within an area roughly 1/8 square mile (75.66 Acres), which is not an insignificant number. But while the City appears to be waiting to incorporate information from pending traffic studies to determine ARB’s actual impact, the City has at least identified the 7400 South extension as a “key traffic distributor to other arterial streets . . . in the future phases of the project,” naming 5600 West and U-111, both of which are situated within about a half-mile from the development. The City appears to have the solution before it has identified the problem, which calls the related nature of the exaction into question. Further, while the stated solution is to extend 7400 South in order to distribute traffic to other arterial streets, like 5600 West, specifically, because the current road dedication will only extend 7400 South as a continued dead-end street (because Mountain View Corridor is not yet in Phase 2 to allow for an overpass), the stated objective of traffic distribution does not appear to be accomplished by this condition.

For the City to lawfully require dedication of private property without compensation for the connection in question, the need for 7400 South for traffic distribution must exclusively be a result of the additional traffic produced by Bowman’s Arrow’s new 2,000 units, and not a result of impacts created by other surrounding development, either current or future. And, the City’s condition—or solution to the problem caused by the development—needs likewise to be related to that problem. If the rough proportionality standard asks that impact and conditions be viewed as a problem and solution, respectively, then a solution that does not actually solve the problem it is stated to address does not appear to be related or proportionate.

The City must eventually make an individualized determination regarding whether the exaction is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to ARB’s proposed impact. The information thus far presented to this Office suggests that requiring ARB to construct the 7400 South extension would fail the nature aspect of the rough proportionality test. The City has not provided evidence to support a conclusion that the exaction would offset the impact of ARB’s proposed development, and nothing more. Absent such evidence, it is difficult to see how an imposed road dedication, identified as necessary for future traffic distribution, will be able to distribute traffic and offset ARB’s development impacts when the road currently exists as a dead-end street.

Conclusion

In response to ARB’s request for development, the City’s requirement that property be dedicated for construction of a road is a development exaction, regardless of whether the City asks for it as a condition precedent to favorable legislative action, or as a condition subsequent in exchange for administrative approval, and must satisfy the rough proportionality standard for exactions. The City bears the burden of making an individualized determination that the condition imposed satisfies this standard, and is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the proposed impact of the development. The information available does not support the conclusion that the City’s imposition of a road exaction would be proportionate to ARB’s impact.

Jordan S. Cullimore, Lead Attorney

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

Note

This is an advisory opinion as defined in § 13-43-205 of the Utah Code. It does not constitute legal advice, and is not to be construed as reflecting the opinions or policy of the State of Utah or the Department of Commerce. The opinions expressed are arrived at based on a summary review of the factual situation involved in this specific matter, and may or may not reflect the opinion that might be expressed in another matter where the facts and circumstances are different or where the relevant law may have changed.

While the author is an attorney and has prepared this opinion in light of his understanding of the relevant law, he does not represent anyone involved in this matter. Anyone with an interest in these issues who must protect that interest should seek the advice of his or her own legal counsel and not rely on this document as a definitive statement of how to protect or advance his interest.

An advisory opinion issued by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman is not binding on any party to a dispute involving land use law. If the same issue that is the subject of an advisory opinion is listed as a cause of action in litigation, and that cause of action is litigated on the same facts and circumstances and is resolved consistent with the advisory opinion, the substantially prevailing party on that cause of action may collect reasonable attorney fees and court costs pertaining to the development of that cause of action from the date of the delivery of the advisory opinion to the date of the court’s resolution.

Evidence of a review by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman and the opinions, writings, findings, and determinations of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman are not admissible as evidence in a judicial action, except in small claims court, a judicial review of arbitration, or in determining costs and legal fees as explained above.

The Advisory Opinion process is an alternative dispute resolution process. Advisory Opinions are intended to assist parties to resolve disputes and avoid litigation. All of the statutory procedures in place for Advisory Opinions, as well as the internal policies of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman, are designed to maximize the opportunity to resolve disputes in a friendly and mutually beneficial manner. The Advisory Opinion attorney fees provisions, found in Utah Code § 13-43-206, are also designed to encourage dispute resolution. By statute they are awarded in very narrow circumstances, and even if those circumstances are met, the judge maintains discretion regarding whether to award them.

Endnotes

[1] Mountain View Corridor (MVC) is planned to be constructed in phases. Phase 1 construction involves construction of a two-lane road in each direction with regular full-stop intersections. Phase 2 involves the conversion of MVC into a full freeway with grade-separated intersections (i.e., on and off-ramps and bridges over existing arterial roads. The portion of MVC adjacent to the ARB parcel is currently improved in Phase 1, with no determination from UDOT on the timing of Phase 2.

[2] West Jordan City Code § 13-6K-2 (2019). At the time of the Request for an Advisory Opinion, this section included areas impacted by both Mountain View Corridor and Bangerter Highway, however, this section appears to have been recently amended to now be limited only to Mountain View Corridor. See Ordinance No. 21-23 (2021).

[3] The City’s planning staff requested feedback from the City Council regarding the proposed dedication of open space at the northern tip of the parcel, as it would result in the City assuming responsibility for the proposed mountain bike trail and related improvements. The City Council reviewed the plan and made comments at a May 27, 2020 Work Session. This suggests that these comments concluded that the City was fine to remove the open space dedication, but very much expressed that the anticipated right-of-way continuation still be included in the plans.

[4] 5600 West and U-111 appear to be located about roughly ½ mile east and west of the ARB parcel, respectively.

[5] B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake Cty.(B.A.M. I), 2006 UT 2, ¶4, 128 P.3d 1161.

[6] 483 U.S. 825 (1987).

[7] 512 U.S. 374, 114 S. Ct. 2309 (1994).

[8] Utah Code § 13-43-205(1).

[9] Utah Code § 10-9a-103(29) (2021). Note: while this section has been amended since the time of the request for an advisory opinion, no change was made to this particular definition; we therefore cite to the current version of the code.

[10] See Utah Code § 10-9a-103(33) (2021) (“‘Land use regulation’: means a legislative decision enacted by ordinance, law, code, map, resolution, fee, or rule that governs the use or development of land.”).

[11] Utah Code § 10-9a-103(29). A “‘Land use decision’ means an administrative decision of a land use authority . . . regarding . . . a land use application,’” § 10-9a-103(31), to which land use regulations are applied. § 10-9a-306.

[12] The City states that West Jordan City Code (“City Code”) requires streets to be dedicated and constructed as follows: (a) in compliance with the Transportation Master Plan (City Code§ 14-5-5D); and (b) along subdivision boundaries (City Code § 14-5-50). Since 7400 South Street is in the Transportation Master Plan and is along the “subdivision boundary” of the proposed Bowman’s Arrow development, the City argues, the City Code requires the dedication and construction of 7400 South Street.

[13] B.A.M. I, 2006 UT 2, at ¶4.

[14] Utah Code § 10-9a-508.

[15] West Jordan City Code §§ 14-5-5D, 14-5-5G.

[16] Jurisdiction for Advisory Opinions in our Office is understandably different than the justiciability standards for courts in the judicial system. Quite appropriately, courts refer to issues that are not “ripe” for judicial review as constituting impermissible “advisory opinions.” See Baird v. State, 574 P.2d 713, 715 (Utah 1978) (“To entertain an action for declaratory relief, there must be a justiciable controversy, for the courts do not give advisory opinions upon abstract questions”). In contrast, that is the very purpose of the opinions provided by the Ombudsman’s Office, as a request for a written advisory opinion must generally be made before the deadline to file a particular action in district court. See Utah Code § 13-43-205(1)(b). In other words, once an issue becomes ripe for the district court to consider, the time for an Ombudsman’s opinion is typically past.

[17] See, B.A.M. I, 2006 UT 2, at ¶34.

[18] Utah Code § 13-43-203(1)(f).

[19] See West Jordan City Code § 13-5A-3 (providing that the A-20 agriculture zoning designation has a 20 acre minimum lot size, with no more than one single-family dwelling per lot).

[20] Stop the Beach Renourishment v. FL DEP (holding that courts are subject to the same takings restrictions as the legislative or executive branches of governments–states effect a taking if they, by judicial decree, recharacterize as public property what was previously private property).

[21] See, Spencer v. Pleasant View City, 2003 UT App 379, ¶ 18, 80 P.3d 546, 551 (a property owner has no vested property right in a contemplated development or subdivision).

[22] The “unconstitutional conditions” doctrine vindicates the Constitution’s enumerated rights by preventing the government from coercing people into giving them up, even when the government threatens to withhold a gratuitous benefit. See, e.g., United States v. American Library Assn. Inc., 539 U. S. 194, 210, 123 S. Ct. 2297, 156 L. Ed. 2d 221.

[23] In Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Mgmt. Dist., the United States Supreme Court considered whether the Nollan/Dolan “rough proportionality” test still applied where, instead of affirmatively approving a land use permit on the condition that the applicant turn over property, the government instead “denies a permit because the applicant refuses to do so.” 570 U.S. 595, 606, 133 S. Ct. 2586, 2595 (2013).

In Koontz, a Florida landowner’s property was considered wetlands, and in order to develop, the landowner had to obtain permits from St. Johns River Water Management District (District). Florida law requires permit applicants wishing to build on wetlands to offset the resulting environmental damage. Koontz proposed to mitigate the effects of his development by deeding nearly three-quarters of his property as a conservation easement. The District rejected this proposal and instead stated that it would only approve construction if he (1) further reduced the size of his development and deeded the larger remainder to the District in fee or (2) hired contractors to make improvements to District-owned wetlands several miles away. Koontz filed suit challenging the demands as excessive and constituting a taking without just compensation. The State Supreme Court held that the claim failed under Nollan and Dolan because, unlike those cases where imposed conditions on approvals amounted to illegal exactions, the District had only denied the application.

While not apparent from the Supreme Court’s opinion itself, scholarship on the lower court history of the Koontz case makes clear that “the District at all times retained the regulatory authority to prohibit use of the property to protect the health and safety of the public by preserving the ecosystem services that Koontz’s property, in its natural state, provides,” however, “the District proved willing to discuss possible avenues for mitigating the impacts of the proposed development through imposition of an exaction.” ARTICLE: PROPOSED EXACTIONS, 26 J. Land Use & Envtl. Law 277, 290 (emphasis added).

In reversing the Florida ruling, The United States Supreme Court in Koontz held that the “unconstitutional conditions” doctrine, which provides that the government cannot coerce people into giving up constitutional rights, applied to the right to just compensation for property under the Takings Clause. The Court explained: “So long as the building permit is more valuable than any just compensation the owner could hope to receive for the right-of-way, the owner is likely to accede to the government’s demand, no matter how unreasonable.” 570 U.S. 595, at 605. Because of this, the Court held that the government’s demand for property from a land-use permit applicant must satisfy the Nollan/Dolan requirements even when it denies the permit, stating, “[e]xtortionate demands for property in the land-use permitting context run afoul of the Takings Clause not because they take property but because they impermissibly burden the right not to have property taken without just compensation.” Id., at 607.

[24] See Utah Code § 13-43-205(1)(a)(i).

[25] West Jordan City Code § 14-5-5D.

[26] West Jordan City Code § 14-5-5G.

[27] B.A.M. I, 2006 UT 2, at ¶46.

[28] Dolan v. City of Tigard, 512 U.S. 374, 391, 114 S. Ct. 2309, 2319-20 (1994).

[29] The standard for whether a land use regulation is, on its face, constitutionally valid, is whether it is “reasonably debatable” that it is in the interest of the general welfare, see Marshall v. Salt Lake City, 105 Utah 111, 121-22, 141 P.2d 704, 709 (Utah 1943), which is admittedly a much lower bar than “roughly proportionate.” See generally, Wash. Townhomes, LLC v. Wash. Cty. Water Conservancy Dist., 2016 UT 43, 388 P.3d 753 (discussing differing standards of review in the context of Nollan/Dolan).

[30] See Banberry Dev. Corp. v. S. Jordan City, 631 P.2d 899, 903 (Utah 1981).

[31] Contrasted, for example, with our Office’s jurisdiction to otherwise mediate or arbitrate disputes “involving taking or eminent domain issues” in other contexts, wherein our Office maintains discretion to decline to mediate or arbitrate for certain reasons, where appropriate. See Utah Code § 13-43-204(1), (3)(b).

[32] One, because it will exceed discretionary powers granted by State statute under Section 10-9a-508, but second because it will violate protections guaranteed by the Takings Clauses of the Utah and U.S. Constitutions.

[33] Utah Code § 10-9a-508.

[34] B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C v. Salt Lake Cty. (B.A.M. II), 2008 UT 74, ¶ 10, 196 P.3d 601 (emphasis added).