Advisory Opinion 182

Parties: Ivins City

Issued: March 29, 2017

Topic Categories:

Exactions on Development

The requirements imposed by a local zoning code control development in that zone. When requirements result in dedication of property to the public, that requirement is an exaction, and must be reviewed under the “rough proportionality test.” Requirements that do not result in dedication are not exactions and are analyzed under the regulatory takings test.

DISCLAIMER

The Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman makes every effort to ensure that the legal analysis of each Advisory Opinion is based on a correct application of statutes and cases in existence when the Opinion was prepared. Over time, however, the analysis of an Advisory Opinion may be altered because of statutory changes or new interpretations issued by appellate courts. Readers should be advised that Advisory Opinions provide general guidance and information on legal protections afforded to private property, but an Opinion should not be considered legal advice. Specific questions should be directed to an attorney to be analyzed according to current laws.

Advisory Opinion

Advisory Opinion Requested by:

Dale T. Coulam, City Attorney

Local Government Entity:

Type of Property:

Commercial

March 29, 2017

Opinion Authored By:

Brent N. Bateman

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

Issues

Are Ivins City’s setback ordinances and road construction requirements legal?

Summary of Advisory Opinion

Ivins City’s setback ordinances, as applied to the property at the corner of 200 East and Highway 91, restrict the use of the property but do not necessarily result in a regulatory taking. They do not deprive the property of all economically viable uses of the land. However, the same setback regulations could be illegal when applied to other properties, if they go too far.

Ivins City’s requirements to dedicate and construct any portion of a road or trail/sidewalk are exactions and are analyzed using the rough proportionality rule. The recommended trails within the landscape buffers, if they are to be used by the public, are dedicatory and are thus exactions rather than simple landscape requirements. The legality of those exactions depends on the development that will occur, and whether the exactions are roughly proportionate to the impacts created by the development.

Review

A Request for an Advisory Opinion may be filed at any time prior to the rendering of a final decision by a local land use appeal authority under the provisions of Utah Code § 13-43-205. An advisory opinion is meant to provide an early review, before any duty to exhaust administrative remedies, of significant land use questions so that those involved in a land use application or other specific land use disputes can have an independent review of an issue. It is hoped that such a review can help the parties avoid litigation, resolve differences in a fair and neutral forum, and understand the relevant law. The decision is not binding, but, as explained at the end of this opinion, may have some effect on the long-term cost of resolving such issues in the courts.

A Request for an Advisory Opinion was received from Mr. Dale T. Coulam, Ivins City Attorney, on behalf of City of Ivins, on December 7, 2016. A letter was sent to Mr. Coulam acknowledging his request for an advisory opinion, via regular US Postal Service to Ivins City Attorney’s Office, 55 North Main St., Ivins, Utah 84738.

Evidence

The Ombudsman’s Office reviewed the following relevant documents and information prior to completing this Advisory Opinion:

- Request for an Advisory Opinion submitted by Mr. Dale T. Coulam, City Attorney, on behalf of the City of Ivins, on December 7, 2016.

Background

Ivins City has three potentially conflicting policies regarding building setbacks. All three have converged on a parcel located at the corner of 200 East and Highway 91. Ivins has requested this Advisory Opinion to determine whether these setbacks actually do set them back.

The first setback provision arises in Ivins City Zoning Ordinance § 16.19.102, and thus represents the actual law in Ivins. This provision provides two setbacks scenarios:

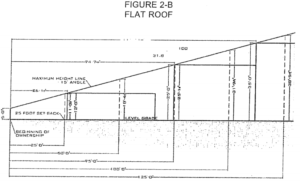

Properties adjacent to [Highway 91 – along its entire length] shall be limited to setbacks and building heights to the extent reasonably feasible as per figures 2-A and 2-B of this section, or to the actual view angle if determined to be greater than fifteen degrees (15) using methods similar to those used in said figures 2-A and 2-B to preserve significant views. Where none of the above stated views are compromised or when the view angle to such views is less than fifteen degrees (15), then the minimum setback shall be thirty feet (30’). If the view angle calculation determines a setback greater than thirty feet (30), then up to one-third (1/3) of a building, or cluster of buildings, can extend to the minimum setback.

According to this provision, the setbacks along Highway 91 will be at least 30 feet. If buildings will interfere with certain view corridors, setbacks will increase depending upon building heights. The accompanying image illustrates this 15 degree angle rule.

Ivins City is concerned about this provision because on the 200 East and Highway 91 parcel, it yields a whopping 100 foot setback for a two story building, and an even whoppinger[1] 125 foot setback for a three story building.

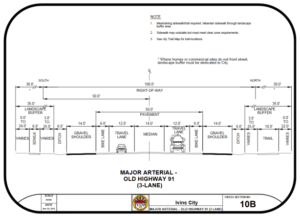

The second setback policy comes from the Ivins City Master Transportation Plan.[2] This setback provision is not text-based. Rather it is represented by a graphic of a highway cross-section. Since even a thousand words would shortchange the value of the picture, it is included here.[3]

This rendering shows a luxurious 100 foot wide right of way, including shoulder and ditch, adjacent to a 30 foot landscape buffer. Within the buffer is a ten foot wide meandering sidewalk or trail.

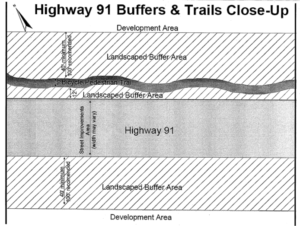

And finally, the third setback policy refers to the Highway 91 Base Corridor Plan and Recommendations, dated June 17, 2004.[4]

Recommended Goals:

- Setbacks of 20-foot minimum and 30-foot average from the highway right of way to provide an open buffer area will be required along both sides of the highway.

- Building setbacks of 50 feet.

A subsequent page of the same document provides an overhead view of Highway 91:

This rendering includes arrows indicating a “40’ minimum, 100’ recommended” landscaped buffer area. These numbers do not match those in the recommended goals above.[5] Thus the Highway 91 Base Corridor Plan appears self-contradictory..

Ivins City has requested this Advisory Opinion to ask which, if any, of these options pass legal muster. Also, the City asks whether it can require the developer to pay all Highway 91 improvement costs adjacent to the project property, including landscape buffer and trail.

Analysis

I. Requirements v. Exactions

An often overlooked distinction arises between requirements and exactions. This distinction is important because although all exactions are requirements, not all requirements are exactions.[6] Exactions and requirements are analyzed differently, and both arise in this Advisory Opinion.

Most zoning codes contain many requirements. Indeed, a zoning code that doesn’t impose requirements is like a wienerdog on a pheasant hunt: there’s no point. The requirements imposed by a zoning code control development within that zone. Requirements limit uses, establish densities, dictate setbacks, restrict heights, frustrate developers, limit animals, control landscaping, enflame neighbors, and many similar verb-object pairs. Zoning requirements can be made mandatory by being adopted into the local ordinance. Authority to create ordinances arises under the local government’s police power to establish laws to ensure the health, safety, and welfare of a community. See Marshall v. Salt Lake City, 141 P.2d 704, 708 (Utah 1943) (“City zoning is authorized only as an exercise of the police power of the state. It must therefore have for its purpose and objectives matters which come within the province of the police power.”).

Exactions, on the other hand, are dedications to the public of private property as a condition of development approval. See Dolan v. City of Tigard, 512 U.S. 374, 386 (1994). The classic example of an exaction is a requirement to dedicate land and build a road. If the City requires a developer, as a condition of approval, to give land to the City for the road, and/or to give money to construct the road, the requirement that the City has imposed is an exaction.

Thus the primary distinction between a requirement and exaction is a requirement requires a developer to do something with his or her own property, whereas an exaction requires the developer to give property away to the public. See also B.A.M. Dev., L.L.C. v. Salt Lake County, 2006 UT 2, ¶ 34,128 P.3d 1161, 1169 (“[E]xactions resemble physical takings in the sense that they typically require the permanent surrender of private property for public use.”). Exactions are a type of requirement, but requirements that do not require public dedication of property are not exactions. Setback requirements are usually not exactions, because no dedication to the public is usually required. Typically, the owner keeps and can use the land within the setback. However, when the owner is required to give property to the public or construct public improvements within or without a setback area, it becomes an exaction.

II. The Ivins City Setback Requirements

A City may require buildings and other development activity to be set back a certain distance from the public street, in order to advance the public health, safety, and welfare of the community. In most circumstances, the setback area remains in the ownership of the property owner and is not dedicated to the public.

Under Utah law, zoning and land use ordinances are deemed valid, unless it can be shown that they are arbitrary, capricious, or illegal. Bradley v. Payson City Corp., 2003 UT 16, ¶10. A zoning or land use ordinance is considered not arbitrary or capricious “if it is reasonably debatable that the decision, ordinance, or regulation promotes the purposes of this chapter and is not otherwise illegal.” Utah Code § 10-9a-801(3)(b). Thus, if a particular zoning restriction, such as a setback, is adopted by ordinance, it is deemed valid unless (1) it is not reasonably debatable that the setback promotes the purposes of LUDMA,[7] or (2) is illegal. Reasonably debatable is a very low standard. So low, in fact, that no point exists in wasting the droplet of ink needed to discuss it further. All that is left, then, is to examine whether the requirement is illegal.

A zoning requirement can be illegal if it goes too far.[8] “The general rule at least is, that while property may be regulated to a certain extent, if regulation goes too far it will be recognized as a taking.” Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 U.S. 393, 415 (1922). A regulation is generally understood to go too far if it wipes out the ability to use the land: “[F]or there to be a taking under a zoning ordinance, the landowner must show that he has been deprived of all reasonable uses of his land.” Cornish Town v. Koller, 817 P.2d 305, 312 (Utah 1991). A reasonable use, or economically viable use, does not mean the “highest and best use.” Smith Inv. Co. v. Sandy City, 958 P.2d 245, 259 (Utah Ct. App. 1998). Generally where economic value remains in the property, no taking has occurred.[9] See Pennsylvania Coal, 260 U.S. at 413. (“Government hardly could go on if to some extent values incident to property could not be diminished without paying for every such change in the general law.”). Thus, if a setback restriction essentially wipes out the economically viable uses of the land, it has gone too far, and is illegal. Short of that, a setback will be presumed valid.

The Ivins City ordinance calls for minimum 30 foot setbacks along Highway 91, and the preservation of a 15 percent view angle. The essence of the ordinance is that buildings must be distanced from the highway in order to fit within that 15 degree angle. For a two story building to fit within that view angle, it must be 100 feet from the road, and the three story building must be 125 feet away. One hundred feet represents a very large and alarming setback. However, the requirement is not necessarily illegal. It may help to view Ivins City’s 15 degree view angle not as a setback ordinance, but as a building height ordinance. A one-story building appears to have no problem fitting into the 15 degree angle when set back 30 feet from the property line. Taller buildings must be set back further to fit within the 15 degree window. Certainly requiring them to be built 100 feet from the property line is a really long way. But prohibiting two-story and three-story buildings close to the road does not inherently deprive the property of economically viable use. One-story buildings are an economically viable use, and can occupy the land close to the road. Taller buildings can exist on the property, but must be located farther from Highway 91.

Thus if a structure can be built, even limited to single story structures, then economic value remains in the property. The regulation is then presumed valid and has not gone too far. A property owner may have the right to build upon the land, but there is no inherent right to have a three-story building close to the road. Accordingly, the Ivins City ordinance does not go too far on the corner of 200 East and Highway 91.

Much will depend, of course, on the size and shape of the parcel itself. On the corner of 200 East and Highway 91, the requirement does not appear to deprive the owner of economically viable use of land. Of course, on parcels of different size and shape, application of this ordinance could go too far and deprive the owner of economically viable uses. In such a case, a variance, ordinance change, or purchase of property may be needed to remedy a possible unconstitutional taking. Nevertheless, no inherent illegality can be found in the default 30 foot setback ordinance, nor the 15 degree view angle requirement.

III. The Ivins Road Improvement Exactions

The remaining provisions, the Ivins City Transportation Master Plan and the Highway 91 Base Corridor Plan and Recommendations,[10] include exactions and must be analyzed differently. Both of these documents show, seemingly as setbacks, large landscape buffer zones on each side of the road. But these buffer zones, 30 feet wide on the Transportation Master Plan, and various widths on the Base Corridor Plan, are not mere setbacks. Included in each of those buffers is a meandering trail or sidewalk. Although the text does not require dedication of this area unless the “homes or commercial sites do not front street,” the trail or sidewalk will presumably be used by the public. If the public will use the property, dedication is required. Some public easement or right-of-way must arise in order to give people the right to use the sidewalk. Otherwise, the trail can only benefit the property owner and all others who use the trail trespass. Accordingly, although the graphic indicates that the landscape buffer is normally not dedicated, the appearance of a trail or sidewalk within that buffer indicates that it must be dedicated, at least in part. Since that area is to be dedicated to the public, it is an exaction, and not merely a setback.

Exactions are analyzed under the rough proportionality test found in Utah Code § 10-9a-508(1):

(1) A municipality may impose an exaction or exactions on development proposed in a land use application, including, subject to Subsection (3), an exaction for a water interest, if:

(a) an essential link exists between a legitimate governmental interest and each exaction; and

(b) each exaction is roughly proportionate, both in nature and extent, to the impact of the proposed development.

This test, borrowed directly from the U.S. Supreme Court analyses in Nollan v. California Coastal Comm’n, 483 U.S. 825 (1987) and Dolan v. City of Tigard, 512 U.S 374 (1994), and refined in Utah in B.A.M. Development, LLC v. Salt Lake County, 2008 UT 74, seeks to determine whether the dedication is roughly proportionate in both nature and extent to the cost to the City to assuage the development’s impact. If the exaction passes this test, being roughly proportionate to the impact created by the development, it is legal. Otherwise, it fails.

Whether or not an exaction is roughly proportionate, of course, depends on the impact of the development. A development with a greater impact will justify a greater exaction. Smaller impacts require smaller exactions. All of these combined costs, including the land dedicated to public use, costs of construction of improvements upon that land, etc., must together be roughly proportionate to the impacts created by the development.

Analysis of these exactions is impossible without knowing what is being developed. Impacts cannot be determined until the development is presented. For now, suffice to say that the cross-section from the Transportation Master Plan, and the Base Corridor Plan each require some exactions, and do not simply represent required landscaping within setbacks.

Conclusion

The Ivins City setback requirements, although appearing very large, are really restrictions regarding building heights, and do not go too far because they do not deprive the owner of all economically viable use of the land. Ivins City’s plans and recommendations are exactions, in that they require the dedication of land within the landscape buffer. Any dedication must be considered an exaction once development impacts are determined. The exaction and the impacts must be roughly proportionate to one another.

We recommend that Ivins City consider clear and objective setback standards along Highway 91 that meet their community goals. We further recommend that the City adopt into ordinance clear road standards that include sidewalks and landscape buffers. Going forward, as applications to develop are received, we recommend that the City examine whether their setbacks go too far as applied to the property, and examine the exactions it would like to impose. Having carefully reviewed the impacts, the City should ensure that its exactions are proportionate to those impacts.

Brent N. Bateman, Lead Attorney[11]

Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman

Note

This is an advisory opinion as defined in § 13-43-205 of the Utah Code. It does not constitute legal advice, and is not to be construed as reflecting the opinions or policy of the State of Utah or the Department of Commerce. The opinions expressed are arrived at based on a summary review of the factual situation involved in this specific matter, and may or may not reflect the opinion that might be expressed in another matter where the facts and circumstances are different or where the relevant law may have changed.

While the author is an attorney and has prepared this opinion in light of his understanding of the relevant law, he does not represent anyone involved in this matter. Anyone with an interest in these issues who must protect that interest should seek the advice of his or her own legal counsel and not rely on this document as a definitive statement of how to protect or advance his interest.

An advisory opinion issued by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman is not binding on any party to a dispute involving land use law. If the same issue that is the subject of an advisory opinion is listed as a cause of action in litigation, and that cause of action is litigated on the same facts and circumstances and is resolved consistent with the advisory opinion, the substantially prevailing party on that cause of action may collect reasonable attorney fees and court costs pertaining to the development of that cause of action from the date of the delivery of the advisory opinion to the date of the court’s resolution.

Evidence of a review by the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman and the opinions, writings, findings, and determinations of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman are not admissible as evidence in a judicial action, except in small claims court, a judicial review of arbitration, or in determining costs and legal fees as explained above.

The Advisory Opinion process is an alternative dispute resolution process. Advisory Opinions are intended to assist parties to resolve disputes and avoid litigation. All of the statutory procedures in place for Advisory Opinions, as well as the internal policies of the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman, are designed to maximize the opportunity to resolve disputes in a friendly and mutually beneficial manner. The Advisory Opinion attorney fees provisions, found in Utah Code § 13-43-206, are also designed to encourage dispute resolution. By statute they are awarded in very narrow circumstances, and even if those circumstances are met, the judge maintains discretion regarding whether to award them.

Endnotes

[1] “So shall my lungs coin words till their decay.” Shakespeare, Coriolanus III.1.

[2] Nothing has been provided to indicate that the Master Transportation Plan has the force of law in Ivins.

[3] Enjoyment of this graphic is certainly enhanced by the depiction of an apparent hazardous materials truck traveling through downtown Ivins City.

[4] These recommendations also have not been adopted into Ivins City law as far as can be determined.

[5] There may be some unfound explanation for these disparate numbers. In my experience, engineers rarely make mistakes with numbers and can usually find an algorithm to explain even the most apparent errors. Those explanations, in my experience, often involve something called “imaginary numbers,” which I can only assume means numbers such as eleventeen or sixtytwelve. In any event, reconciling these numbers is not critical to the result of this Advisory Opinion.

[6] That helpful sentence will hopefully be better explained below.

[7] LUDMA is an acronym for Land Use, Development, and Management Act, Utah Code § 10-9a-101 et seq., and is shorthand for the “this chapter” referred to above.

[8] A zoning requirement may be illegal for multiple reasons, such as directly contradicting a state statute. Our discussion here is limited to whether the requirement amounts to an unconstitutional regulatory taking.

[9] A taking may also arise under the burdens vs. benefits balancing test in Penn Central Transp. Co. v. New York City, 438 U.S. 104 (1978). However, application of this test would not yield a different result.

[10] It’s worth noting again that neither appears to have the force of law. Although planning documents are adopted in a legislative process, they are usually considered advisory only. “[T]he general plan is an advisory guide for land use decisions, the impact of which shall be determined by ordinance.” Utah Code § 10-9a-405. A planning document can be given the force of law through express adoption into ordinance. However, nothing was provided to so indicate here.

[11] Please do not mistake the few attempts to inject a light-hearted comment herein for a lack of sincerity or seriousness in responding to the questions presented. They are, rather, an attempt to elicit a smile from the reader in happy celebration of my ten years as Lead Attorney at the Utah Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman, the anniversary of which corresponds with this Advisory Opinion’s release date.